by Patrick Morgan Monday, August 1, 2016

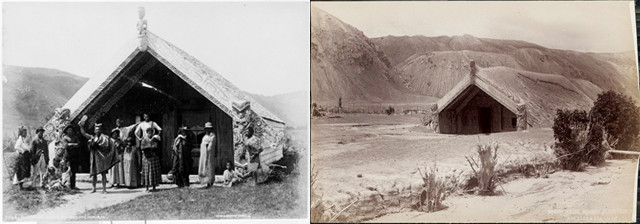

Hinemihi meeting house at Te Wairoa, before the Mount Tarawera eruption in 1886 (left) and after the eruption (right). It was moved to Clandon Park in Surrey, England, in 1892 by the British Governor General of New Zealand. Today it is once again used as a meeting house by the Māori community in England. Credit: Left: Burton Bros, Dunedin, courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library; right: photograph taken circa 1886 by Edmund Wheeler and Son, courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library.

On June 10, 1886, Mount Tarawera on New Zealand’s North Island erupted catastrophically, killing more than 100 people. With few warning signals, the explosive basaltic eruption caught many people by surprise as it rocked the mountain, forming fissures that extended for 17 kilometers into the adjacent Lake Rotomahana and Waimangu Valley.

Tarawera is composed of a series of rhyolitic lava domes that formed during an eruption in A.D. 1314. It is a member of a group of volcanic vents called the Okataina Volcanic Center, which also includes volcanoes such as Haroharo, Mt. Edgecumbe, Okareka and Rotoma. Known for their large eruptions, the Okataina volcanoes have erupted in the past in intervals ranging from 700 to 3,000 years.

The 1886 eruption, the largest and deadliest volcanic eruption in New Zealand’s recorded history, was heard all the way from Auckland on the North Island to Blenheim on the South Island — more than 500 kilometers away. Standing aboard the ship Glenelg in New Zealand’s Bay of Plenty, 120 kilometers away, Captain Stephenson recalled seeing “large balls of fire, which suddenly appeared, and then broke into a thousand stars,” reported the Bay of Plenty Times newspaper on June 12, 1886.

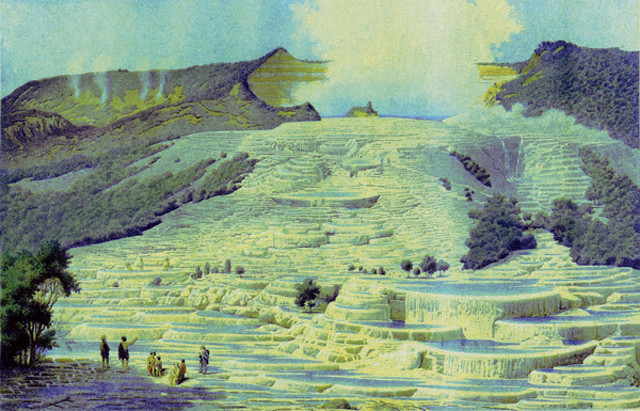

Bruno Hamil's 1860 lithograph of German geologist Ferdinand von Hochstetter talking to the local chief at the White Terraces. Credit: public domain.

The fissures and craters of Mount Tarawera today. Credit: ©Carl Lindberg, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported.

Meanwhile, in Rotorua, 24 kilometers away from Mount Tarawera on New Zealand’s North Island, Postmaster Roger Dansey was celebrating his birthday, he recalled, when the ground began to shake shortly before 1 a.m. An hour later, he “saw an immense column of fire miles in height, rushing up hitherwards with a frightful roar,” according to Ron Keam’s book, “Tarawera: The Volcanic Eruption of 10 June 1886.” Another eyewitness, according to a Radio New Zealand Sound Archive, said that she heard a “violent explosion” and saw “the sky … lit by great flashes of flame, as we watched the mountain bursting forth in violent eruption,” also noting that “great rocks were visible against the bright flames as they were shot into the air.”

In the village of Te Wairoa, near the shores of Lake Tarawera, 21-year-old Clara Haszard, her family and two guests were jolted awake by a rumbling noise at 1:15 a.m. “There was a large inky black cloud hovering over Tarawera,” as reported in Keam’s book, “with lightning and balls of fire shooting out of it … It was like a great sheet of fire.” She heard stones rattling the roof at 3 a.m., as volcanic debris rained down on the house. An hour later, strong winds had toppled the chimney “with such a force that we nearly suffocated with smoke.” As she tried to steady the door, which was bulging from the wind, the roof collapsed. Once outside, Haszard was “struck about the head and body by lumps of debris” and mud before lightning struck the house, bursting the wreck into flames. Haszard and her guests survived by taking shelter in the hen house, and although her mother — pinned in her armchair by roof beams — survived, her father and three siblings died.

No one was sure what was happening. At the Rotoiti timber mill 10 kilometers away from the volcano, a sawmill worker, having heard what sounded like “big guns in the distance,” told A.J. Parks, himself an eyewitness who recounted the events in an interview nearly 70 years after the eruption, that he thought a Russian gun barge was assaulting the coast, “because in those days we had scares about the Russians coming into New Zealand.” Amid the flashes of light, the workers at the mill reported what at first appeared to be a burning, dense fog descending on the camp, but what turned out to be a mass of falling, damp ash that had already piled 22 centimeters high on top of their flat-roofed houses before they could start shoveling it off.

Even though Mount Tarawera consists of a series of rhyolitic lava domes, the eruption was basaltic in nature. The eyewitness reports suggest it started spewing lava by 2:30 a.m., with a fissure opening up and spreading from the northeast side of the volcano toward the southwest into the Waimangu Valley.

As basaltic magma rose, according to Erik Klemetti, an igneous petrologist at Denison University in Ohio, the magma encountered a hydrothermal network underneath Mount Tarawera and Lake Rotomahana, triggering explosive plumes as high as 11 kilometers. Dubbed “Rotomahana Mud,” the ash fall spread all the way to where Captain Stephenson’s ship was moored in the Bay of Plenty. The pyroclastic surge traveled out 6 kilometers from Mount Tarawera at a rate of 40 meters per second, according to Klemetti.

The explosion of Mount Tarawera stripped much of the surrounding landscape of vegetation and spread ash and mud across hundreds of square kilometers. The Māori settlements of Te Ariki, Moura, Te Tapahoro, Totarariki and Waingongongo were all either destroyed or buried. Although estimates of the death tolls range from 108 to 153 people, most records suggest that about 120 people died — a majority of them Māori — including 15 people in Haszard’s village of Te Wairoa.

Aside from the earthquakes in the hours leading up to the eruption, there was at least one other sign of the impending eruption: During the week prior to the volcanic eruption, a series of waves up to 0.3 meters high rolled across Lake Tarawera. Some researchers suggest that these waves indicate that earthquakes had already begun beneath the volcano.

Legends about the events leading up to the eruption have also emerged: On the same day as the odd waves occurred, a group of tourists traveling on Lake Tarawera claimed to have seen a ghost Māori war canoe on the lake. Mrs. R. Sise, an eyewitness who was traveling with her husband and daughter from Dunedin on New Zealand’s South Island, recalled in An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand that the phantom boat “was full of Māoris, some standing up, and it was near enough for me to see the sun glittering on the paddles. The boat was hailed but returned no answer.” The group didn’t think much about the canoe until later that evening, when they learned, according to Sise, that “no such boat had ever been on the lake.”

Another casualty of Mount Tarawera’s eruption were the famed Pink and White Terraces, geothermal springs hailed by some as the eighth wonder of the world, located at the foot of Mount Tarawera along the shores of Lake Rotomahana. These terraces, a major tourist destination, consisted of tiers of silica, over which water cascaded into the lake; pools of water on the higher terraces were too hot for bathing, but visitors — led by Māori guides — would spend time swimming in the lower, lukewarm pools. The White Terraces, or Te Tarata, spread out over 28,327 square meters in a fan shape, and allowed water to cascade down from a height of 30 meters.

Unlike the White Terraces, the smaller Pink Terraces, or Otukapuarangi, were wider toward the top and narrowed as water fell 23 meters into the lake. “In the bath,” wrote Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope in his book, “Australia and New Zealand”: “When you strike your chest against it, it is soft to the touch. You press yourself against it, and it is smooth. You lie upon it, and though it is firm, it gives to you. You plunge against the sides, driving the water over your body, but you do not bruise yourself. I have never heard of other bathing like this in the world.”

The terraces disappeared after the eruption, and since then, it has been a matter of debate as to whether the terraces were blown up by the eruption or merely buried. But in 2011, a group of scientists discovered a section of the Pink Terraces beneath some sediment at the bottom of Lake Rotomahana, at the foot of the volcano.

The discovery was accidental. Researchers from the New Zealand geosciences research group GNS Science, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts and other organizations were mapping Lake Rotomahana’s floor to learn more about its geothermal system. Their sonar data revealed crescent-shaped terraces that the researchers reported in a press release comprise the bottom two steps of the Pink Terraces. Although they didn’t find a trace of the White Terraces, the rediscovery of the Pink Terraces, as project leader Cornel de Ronde, a researcher at GNS Science, said in the release, “puts to rest more than a century of speculation as to whether any part of the Pink and White Terraces survived the eruption.”

Although the eruption of Mount Tarawera essentially wiped one tourist destination off the New Zealand map, it also created another: The village of Te Wairoa, where Haszard and her family experienced the 1886 eruption, is now an exhibit open to the public, revealing the excavated ruins and relics of what is now called The Buried Village.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.