by Timothy Oleson Monday, June 16, 2014

Brig. Gen. Zebulon Pike depicted during the War of 1812. Credit: Library of Congress.

Of America’s early 19th-century western explorers, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark typically garner the most attention. But there was a third military man who, along with a detachment of U.S. Army troops and volunteers, also trekked into the newly acquired reaches of the young United States in the same era: Zebulon Pike.

Pike’s ambitious 1806 journey marked the first official U.S. exploration of the southern Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. Today, this expedition is perhaps remembered more for its seeming — though never fully illuminated — ties to the so-called Burr Conspiracy and the duplicitous General James Wilkinson. Nonetheless, Pike may have done just as much as his more recognized counterparts to “open” the continent to American expansion. And he and his men are credited as the first European Americans to lay eyes on and document many remarkable physical features, from major rivers to the famous peak that bears his name.

Born in New Jersey in 1779, Pike joined the U.S. Army at a young age and, after serving stints at various frontier outposts, was stationed at Fort Bellefontaine near St. Louis. While there, Pike befriended James Wilkinson, who was the Commanding General of the Army and had been appointed by President Thomas Jefferson as the first governor of the vast Louisiana Territory following its acquisition from France in 1803.

Jefferson was eager to explore and consolidate American authority in the country’s new territory, especially given that Spain — which controlled the lands to the south and west of Louisiana — still considered parts of the territory disputed ground. To that end, Lewis and Clark’s band struck out across the northern Great Plains and Oregon Country in May 1804. The following year, Pike was sent north to make contact with Native American tribes and search for the headwaters of the Mississippi River.

After Pike returned in April 1806 from this initial foray, Wilkinson soon ordered the young lieutenant off again, this time on a route that would take him west and south. He would be accompanied by 23 men — mostly enlisted soldiers, as well as a volunteer doctor, John Robinson, and General Wilkinson’s son, Lt. James B. Wilkinson, second-in-command to Pike.

The stated goals of the trip were to escort several dozen Osage Indians recently freed from captivity back to their homelands; to make contact with other tribes, including the Pawnee and Comanche; to locate and explore the headwaters of the Arkansas and Red rivers; and, finally, to return east along the Red, which skirted the ill-defined southwestern border of the Louisiana Territory.

Unlike Lewis and Clark’s expedition — overseen and commissioned by Jefferson — Pike’s second excursion was hurriedly planned and launched by General Wilkinson, without prior consent from the president or the War Department (although it was later approved). Its diplomatic and exploratory aims notwithstanding, there is little doubt that Pike’s expedition was also intended, in part, as a surreptitious reconnaissance effort to gauge Spanish strength and monitor their operations over the border.

Wilkinson had standing orders to gain intelligence about Spanish activity when possible. But he almost certainly also had ulterior motives in ordering the mission. Exactly what these motives were — possibly intending for Pike’s men to enter Spanish territory and be captured, either to better spy on, or serve, Spanish interests — and to what extent Pike was aware of them, has remained unclear. Wilkinson was soon to be implicated in then-former Vice President Aaron Burr’s alleged schemes to split Louisiana from the U.S. (and possibly invade Spanish Texas) for the purpose of forming a separate nation. (Burr was later charged with treason in what became known as the Burr Conspiracy. He denied the allegations and was acquitted due to lack of evidence.) Years after Wilkinson’s death in 1825, it was revealed that he had also received payments from Spanish officials beginning in the 1780s, confirming his status as a longtime double agent.

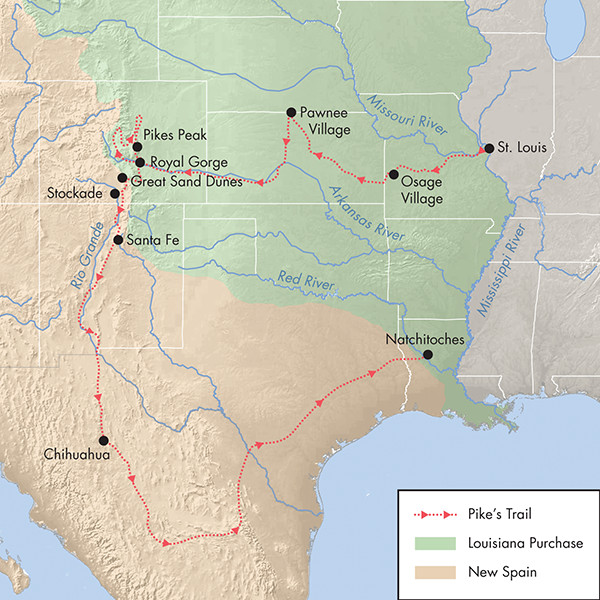

The route that Pike's expedition traveled between July 1806 and June 1807. Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI.

Whatever the motivations for the expedition, Pike, his troop and 51 Native Americans left Fort Bellefontaine on July 15, 1806. Following the Missouri River to the Osage River, the party reached the Osage villages in far western Missouri in mid-August, quickly accomplishing the first goal of the trip. In early September, the group left the Osage camp and headed northwest to an encampment of Pawnee on the Republican River near the present-day border of Kansas and Nebraska.

There, Pike communicated news of the American acquisition of Louisiana to the tribe, longtime trading partners with New Spain, but failed to convince them to help him locate and negotiate with the Comanche, who were deemed a potentially important ally to the U.S. in consolidating control of the territory. After two weeks, Pike set off south, in search of the Comanche and tracing the path of a large Spanish force who had, shortly before the Americans’ arrival, visited the Pawnee village themselves to reaffirm their own relations with the tribe and who had been sent to intercept Lewis and Clark’s group.

Two hundred kilometers to the south, Pike’s party found themselves on the banks of the Arkansas River near the present-day town of Great Bend, Kan. After another respite, Lt. Wilkinson and a detachment of five men departed downstream in late October to return east and report on the journey so far. Meanwhile, Pike and the remaining group headed upstream — still following the trail of the Spanish forces — to continue their search for the Comanche (whom they never did encounter) and press on toward the source of the Arkansas.

Along the way, Pike made assiduous observations of the weather, wildlife and terrain as they traversed westward through increasingly arid and treeless prairie. For food, they hunted bison, whose “numbers exceeded imagination,” as Pike later recounted.

By mid-November, still following the Arkansas River, the group had crossed into what is now Colorado. Despite dropping temperatures and the lack of provisions for winter, Pike pressed on. Days later, on Nov. 15, the party spied the first peaks of Rockies on the horizon, including, notably, a majestic “blue mountain” that Pike called “Grand Peak.”

On Nov. 24, Pike and three others left the rest of the party near present-day Pueblo, Colo., and set off in an attempt to ascend the peak and gain a better vantage on the suddenly mountainous terrain. Mistaking the 3,500-meter-tall Mount Rosa as their intended target, however, the foursome fought through bitter cold and deep snow and reached the summit of the smaller mountain, only to then realize that the taller “Grand Peak” still lay farther away. Their decision to turn back to rejoin the rest of the group meant that Pike would never actually set foot on the mountain that would come to be named Pikes Peak (see sidebar).

Pike and his men spent weeks meandering through the southern Rockies, beset by harsh weather and led astray by difficult navigation. Thinking they had found the Red River at last in late December, the group followed the flow downstream until, reaching the 380-meter-deep Royal Gorge incised into the surrounding granite, Pike realized they had in fact doubled back to the Arkansas River. They then headed south, crossing the Sangre de Cristo Range and spotting the Rio Grande in late January, which Pike evidently also mistook for the Red River.

The expedition made camp on a tributary near present-day Alamosa, Colo., and constructed a stockade. From here, they would attempt rescues of several men and horses — left behind en route due to frostbitten feet and the treacherous terrain — and otherwise wait out winter. By mid-February, however, the governor of Spain’s New Mexico province, into which Pike’s party had crossed — whether wittingly or not is unknown — caught wind of the Americans’ presence. (This was possibly due to the actions of Dr. Robinson, who left the stockade in early February, purportedly to collect business debts from someone in the Spanish-held city of Santa Fe. But he may have instead been working under furtive orders from General Wilkinson, who had hand-picked Robinson for the mission.) On Feb. 26, when a Spanish force of 100 arrived at the stockade, Pike’s group was peacefully taken into custody.

Following their apprehension, Pike and his men were taken to Santa Fe for questioning about the nature of their expedition. They were then marched farther south into Chihuahua, then back up through Texas before being released back into U.S. Territory near Natchitoches in Louisiana at the end of June 1807.

Pike’s expedition did not receive the plaudits that Lewis and Clark’s tour had, but it was nevertheless important for the rapidly expanding U.S. His dealings with the Osage and Pawnee helped set the stage for U.S. alliances with these tribes. And his account of the party’s travels, published in 1810, offered the first widely publicized description of the landscape and climate of the southern High Plains and Rocky Mountains, including numerous rivers, peaks and navigable routes, as well as other remarkable features such as Royal Gorge and the Great Sand Dunes of southern Colorado.

In describing what would become western Kansas and eastern Colorado, he wrote that apart from tree-lined rivers, “these vast plains of the western hemisphere, may become in time equally celebrated as the sand deserts of Africa; for I saw in my route … tracts of many leagues, where the wind had thrown up the sand, in all the fanciful forms of the ocean’s rolling wave, and on which not a speck of vegetable matter existed.” His description contributed to the exaggerated notion of a “Great American Desert,” which delayed widespread settlement of the area for decades.

Lastly, whether intended or not, his parade in captivity through New Mexico, Mexico and Texas provided him an unprecedented view of these southern landscapes and of Spanish colonial authority there, which he passed on to American authorities. After being cleared of any direct role in Burr’s plotting, Pike continued serving in the Army, eventually attaining the rank of brigadier general. He died in 1813, at the age of 34, while leading an attack on the British at York (now Toronto) during the War of 1812.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.