by Kate S. Zalzal Tuesday, December 27, 2016

Ham, the first hominid in space, was named after Holloman Aeromedical Research Laboratory at Holloman Air Force Base in Alamogordo, N.M., where he was trained. Credit: NASA.

Early on the morning of Jan. 31, 1961, a chimpanzee named Ham, outfitted in a diaper, waterproof pants and a space suit, was sealed into a capsule and loaded onto a Mercury-Redstone 2 spacecraft in Cape Canaveral, Fla. Six hours later, Ham the Chimp, named after Holloman Aeromedical Research Laboratory at Holloman Air Force Base in Alamogordo, N.M., where he was trained, became the first hominid to travel into space.

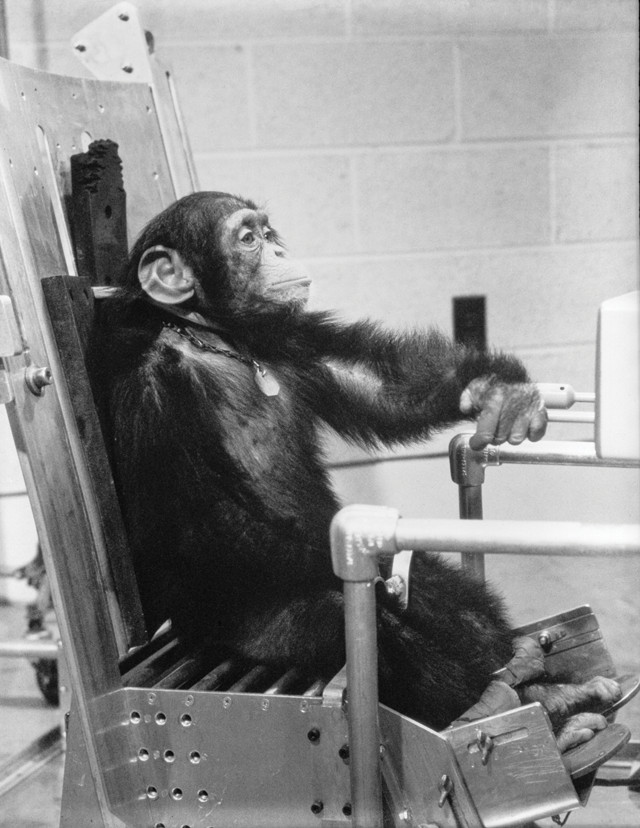

Ham was blasted 240 kilometers above Earth, experiencing speeds up to 9,300 kilometers per hour as well as six and a half minutes of weightlessness. During the crushing forces of take-off and re-entry, sensors monitored Ham’s breathing, heart rate and body temperature. In-flight photographs show that Ham was visibly stressed for parts of his flight, but he was still able to perform a series of experiments that he had been trained to carry out — evidence that humans too could make decisions and execute tasks during space travel.

When, after the 16-minute flight, the capsule landed in the Atlantic Ocean with the chimp safe and sound, a manned mission beyond our world was within reach. Ham’s flight served as the final proof that the American spacecraft system was ready for suborbital flight. A little more than three months later, on May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard became the first American human launched into space and, thanks in large part to the missions of Ham and his predecessors, Shepard returned home safely.

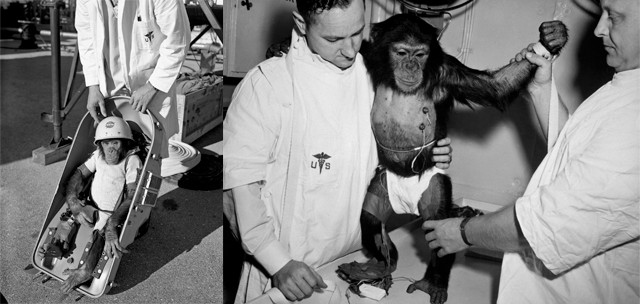

Ham, a week before the launch, shown with the equipment and space suit for his flight. Credit: NASA.

Ham was no doubt a pioneer. But his successful mission was the crowning achievement of several decades of animal testing — trials that included both great successes and disheartening failures. “In our pursuit of space we have asked animals to involuntarily lead the way and demonstrate safety, risks and hazards that should never be first identified by a human space traveler,” wrote Joseph T. Bielitzki, a former NASA chief veterinary officer, in the foreword of the 2007 book “Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle” by Colin Burgess and Chris Dubbs.

During the 1940s and ‘50s, animals were involved in rocket tests at White Sands Missile Range and g-force research at Holloman Air Force Base. The earliest set of primate flights, the Albert Series, consisted of monkeys flying in nose cones of captured German V-2 rockets.

The first of these flights, on June 11, 1948, carried a rhesus monkey named Albert, who was anesthetized and sedated before being launched 360 kilometers above Earth’s surface. Equipment complications delayed the launch and, although the spacecraft also crash-landed after the parachutes failed, it’s thought that Albert perished before take-off due to extreme heat in his capsule. It would be another year before the scientists tried again.

For the second launch, a rhesus monkey named Albert II and another monkey occupied a more spacious capsule that could better protect them against temperature fluctuations. On June 14, 1949, three and a half minutes after liftoff, the pair reached an altitude of 136 kilometers. But disaster struck again when another parachute malfunction caused the nose cone to crash to the ground, killing the monkeys. The recorders in the capsule remained intact however, and respiration and echocardiogram data indicated that the monkeys were in relatively good condition until the moment of impact.

Additional flights carrying both monkeys and mice followed, but explosions or parachute failures prevented the safe return of the animals each time. Although scientists and engineers had major safety hurdles to overcome with the launch and landing process, heart and respiratory data gathered during the flights proved that the animals could survive the trip into space and back.

At Holloman Air Force Base, chimpanzees underwent intense training and medical analysis to see how they would respond to flight and weightlessness. Once they were comfortable being strapped in and wearing equipment, the chimps were trained to perform in-flight experiments. Credit: NASA.

In the early 1950s, rocket technology and animal capsule design improved. The use of Aerobee sounding rockets, capable of hauling a heavier payload, allowed scientists to expand the scope of suborbital biological research. Confident that a human could survive the trip, researchers were interested in the effects of cosmic radiation and in limiting passenger disorientation resulting from weightlessness. But the monkeys aboard the first two Aerobee flights again died, the first in a crash-landing and the second from dehydration.

With a new parachute system installed, the third Aerobee biological flight launched on May 21, 1952, and carried two macaques, Patricia and Michael, along with two mice, Mildred and Albert, nearly 60 kilometers into the atmosphere. As on previous flights, the macaques were anesthetized. But on this flight, they were seated in different orientations for physiological comparisons of how they handled the acceleration. The mice were treated differently as well: One mouse was given a perch to cling to, the other had nothing to grasp within its smooth-walled drum. The mouse with the perch stayed oriented and quiet, while the perch-less mouse hopped disconcertedly around during the brief period of weightlessness. All four animals landed safely and in good health.

The results of the flight would aid in astronaut seating and cabin design. According to Captain David G. Simons, a mission coordinator at Holloman, the series of biological flights proved that weightlessness did not materially harm circulation. “This does not mean that the circulation might not be involved secondarily, due to emotional and automatic reactions to weightlessness. Such secondary reactions are essentially the same whether caused by weightlessness, a rough sea, or an obnoxious mother-in-law,” he wrote in a 1955 report.

In the years between World War II and the onset of Cold War tensions, the emphasis on the military aspect of space exploration diminished, and animal flights were discontinued in the U.S. from 1952 to 1957. During this time, dozens of people came forward, volunteering to be the next subject blasted into space.

By pressing levers in response to a sequence of lights, the chimps could receive treats and water. When performed incorrectly, they received mild electrical shocks on the bottoms of their feet. Credit: NASA.

On Oct. 4, 1957, the Soviet Union stunned the world with its maiden Sputnik mission, putting the first artificial satellite into orbit. Riding the excitement and positive publicity, Soviet scientists launched the first animal into orbit less than a month later.

On Nov. 3, 1957, a dog named Laika achieved immortality as the first animal ever to orbit Earth when her Sputnik 2 R-7 rocket lifted off from Baikonur in Soviet Kazakhstan. Tragically for her, it was a one-way trip: She died five to seven hours into the flight when the heat-dissipating screen and ventilation fan were not able to adequately control the temperature inside the capsule. Sputnik 2 orbited Earth more than 2,500 times before it burned up upon reentering Earth’s atmosphere on April 4, 1958.

Soviet space dogs were being trained for several years prior to Laika’s fateful voyage. Largely strays from the pound or off the streets in Moscow, these dogs went through a battery of tests and preparation for their ballistic missions, with at least eight taking suborbital flights. Despite some losses, these flights continued to prove that living beings could fly to space and survive, at least some of the time.

More than three years would pass before Yuri Gagarin would achieve the coveted prize of becoming the first man to orbit Earth on April 12, 1961. During the intervening time between Laika’s and Gagarin’s missions, the Soviets launched 16 more orbital and suborbital flights carrying dogs, efforts that gathered information for the development of the Vostok rocket that carried Gagarin into space.

The original capsule is now on display at the California Space Center, on loan from the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum. Credit: Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum

The year after Laika, 1958, was a momentous year in space exploration. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed legislation creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on Oct. 1, 1958. A few months later, Project Mercury, the U.S.’s “man-in-space program” was announced. The U.S. also launched its first satellite, Explorer 1, and the Soviet Union lobbed up Sputnik 3, a massive orbiting laboratory.

In the U.S., biological space missions resumed. But landings and recoveries continued to prove difficult, even after successful flights, and several animals were lost. At Holloman, a colony of chimpanzees underwent intense training. Scientists wanted to know how their reflexes would respond to the flight forces and the weightlessness of space. Once they were comfortable being strapped in and wearing space equipment, the chimps in the colony were trained to perform in-flight experiments. By pressing levers in response to a sequence of lights, the chimps could receive treats and water. When performed incorrectly, they received mild electrical shocks on the bottoms of their feet.

The launch of the Mercury-Redstone 2 spacecraft that carried Ham into space from Cape Canaveral, Fla., on Jan. 31, 1961. Credit: NASA

Ham, born in 1957 in the rainforest of what is now Cameroon, was a standout. His easy-going personality made him a favorite of handlers and trainers. On Jan. 2, 1961, Ham and five other candidate chimpanzees traveled to Cape Canaveral, Fla., where they were divided into two colonies as a precaution against disease and illness — much like human astronauts are today. Even the handlers of each colony were not allowed to mingle.

According to Edward Dittmer, an aeromedical technician and chimp trainer at Holloman, they didn’t decide which chimp would go until the day before the launch. Based on his physical well-being and his lever-reflex work, “Ham easily stood out as the best of the bunch,” he later recalled in an interview. caption align=right]

After a 16-minute flight, including six and a half minutes of weightlessness, Ham splashed down in the Atlantic and was retrieved by the U.S.S. Donner, whose captain welcomed him aboard. Credit: NASA.

As the rocket’s nose cone plunged into the sea, eight recovery ships waited. It would take an hour before Ham’s capsule, damaged in the landing and floating precariously, was picked up by a helicopter crew. Ham was agitated and squealing when he was finally unstrapped from his couch, but aside from being slightly dehydrated and suffering a bruised nose from the rough landing, he was in excellent physical shape.

After Ham died in 1983, at the age of 26, some of his remains were buried in front of the International Space Hall of Fame at the New Mexico Museum of Space History in Alamogordo, N.M. Credit: NASA.

Back at Cape Canaveral, Ham was an unwilling celebrity. The throngs of reporters and photographers’ flashbulbs scared him and he refused to pose next to a Mercury training capsule. Ham later trained for a second mission, but another chimp was ultimately chosen for the flight. In 1963, Ham was transferred to the National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C., where he remained a popular attraction. In 1980, Ham was transferred to the North Carolina Zoological Park in Asheboro on long-term loan. He died less than three years later at the relatively young age of 26.

Preliminary calls to stuff and display Ham’s body were dismissed after public outcry. His skeleton was preserved and is still held at the U.S. National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Md., and some of his remains were laid to rest in front of the International Space Hall of Fame at the New Mexico Museum of Space History in Alamogordo, N.M.

Since Ham’s historic flight, animals have continued to have an important role in space exploration. By studying how plants and animals live, grow, reproduce and thrive in space, scientists have gathered volumes of information and gained new understanding that is critical to the pursuit of our next goal — a manned journey to Mars. Much like Ham, animals continue to lead us to the next frontier.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.