by Sara E. Pratt Thursday, December 14, 2017

The spectacle known as firefall — in which burning embers were pushed off Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park to create a flaming cascade — was a beloved tradition for nearly a century. Credit: public domain.

Fifty years ago this month, on Jan. 25, 1968, a massive bonfire built of red fir bark atop Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park was burned down to embers and, promptly at 9 p.m., and for the last time, pushed over the cliff edge to create a flaming cascade for the viewing enjoyment of tourists gathered below. The spectacle, called "firefall," had been a beloved Yosemite tradition for nearly a century.

Although the exact origin of the firefall was not officially recorded, it is known to predate Yosemite’s 1890 designation as a national park.

In 1870, James McCauley, an Irish sailor and miner, arrived in Yosemite Valley and took a job in a sawmill, working alongside John Muir. The next year, he built a trail for which he charged a toll, later called the Four Mile Trail, from the valley floor to Glacier Point, 980 meters above. Hoping to increase traffic on his trail, McCauley then built a small shack atop Glacier Point, called the Mountain House, to provide concessions and lodging to hikers. After initially leasing the house to others to manage, McCauley and his wife, in 1880, leased Mountain House back from the state of California, which had taken possession of all Yosemite claims in 1874. The couple managed the facility — which was described in an 1895 state report as “almost uninhabitable” — until 1897, when they were evicted by the state for failure to maintain it.

It was during this period that McCauley’s school-aged sons — one of whom claimed his father invented the firefall in 1872 when he kicked a campfire over the ledge at Glacier Point — began conducting the firefall as a money-making venture: collecting a fee from tourists in the valley during the day to build a modest fire and push it off the cliff that night.

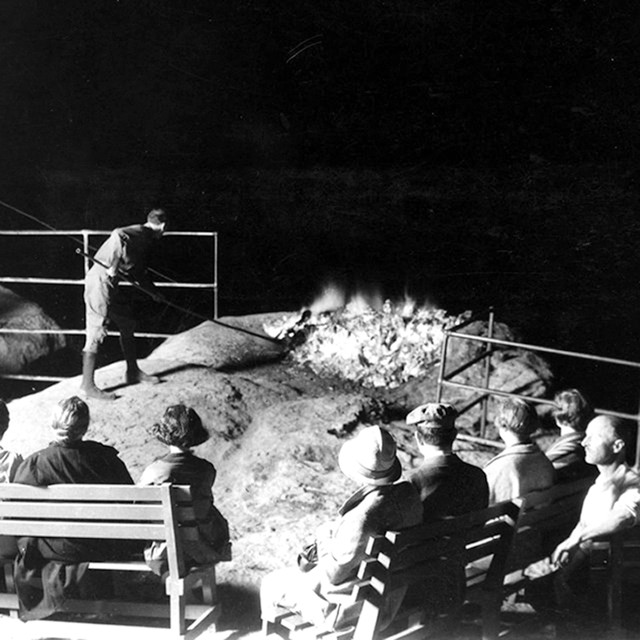

Each night atop Glacier Point, a massive bonfire built of red fir bark was burned down to embers and then pushed off the cliff with long-handled rakes. Credit: National Park Service.

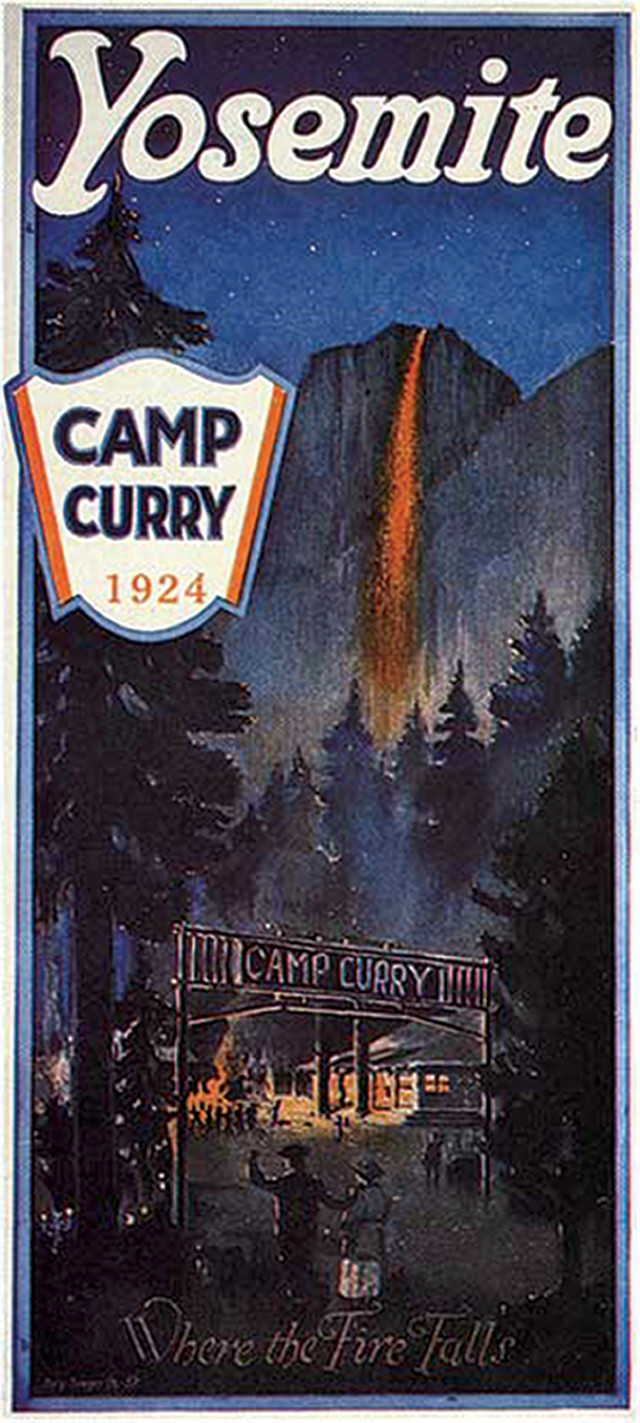

After the McCauleys’ eviction, the firefall was taken up again in the early 1900s by concessioners David and Jennie Curry, who saw an opportunity to draw paying customers to the new camp they opened on the valley floor in 1899. Camp Curry consisted of housekeeping tent cabins, dining facilities, and a stage with outdoor seating that featured nightly variety acts. In 1917, construction of the Glacier Point Hotel, a grand, three-story, 80-room structure, was completed, drawing tourists who wanted to watch the firefall from the point.

In the late 1910s, the tradition was halted for a few years by the park service over a business dispute with the Currys. But by the 1920s, it was back, and the routine that most people would come to know as the firefall began to take shape. Each summer night after the evening’s entertainment, without the aid of a sound system or even a megaphone, the Camp Curry master of ceremonies would cup his hands to his mouth, raise his face toward Glacier Point and bellow: “Hello, Glacier Point!” To which the fire tender at the point would reply: “Hello, Camp Curry!” The rest of the exchange followed: “Is the fire ready?” “The fire is ready!” “Let the fire fall!” “The fire falls!”

Promptly at 9 p.m., the embers were then pushed over the cliff with long-handled rakes, sometimes by two workers alternating strokes to maintain a steady stream of embers and simulate a continuously flowing waterfall. For decades, the song “Indian Love Call,” popularized by Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald in the 1936 film “Rose Marie,” was performed while the fire cascaded down the rock face.

The firefall was halted during World War II, when park facilities were used by the military, and on one famous occasion, it was delayed. In 1960, President John F. Kennedy visited Yosemite and was, according to various sources, either held up by an important phone call or was still eating his dinner at 9 p.m. The firefall was held for half an hour so he could see it — much to the displeasure of the rest of the visitors, as the couple who managed Camp Curry at the time recalled in a 1996 documentary. Otherwise, the firefall occurred each summer night at its regularly scheduled time for nearly two-thirds of the 20th century.

A 1924 promotional flyer depicts visitors gathered at Camp Curry (now known as Half Dome Village) to watch the firefall from Glacier Point nearly a kilometer above. Credit: National Park Service.

While the act of lighting a massive bonfire night after night in a national park and purposefully dispersing the embers over a cliff may be unimaginable to modern national park visitors — who are more familiar with campfire bans to prevent wildfires — the firefall was a hugely popular attraction for thousands of Yosemite visitors each night.

But by the mid-1960s, the spectacle was no longer needed to draw visitors to the park — its original purpose. In 1953, Yosemite received 1 million visitors for the first time, and by 1965, annual visitation had reached 2 million. Additionally, though the firefall never caused any forest fires, other environmental impacts were mounting: Each night, hordes of those visitors, attempting to get the best view, walked out onto the meadows or drove their cars off the park roads. And after each show, rangers worked late into the night untangling traffic jams, while idling vehicles belched exhaust into the air.

“Growing crowds were precisely the reason the park service had been forced [to abolish the firefall], for the agency itself could no longer ignore the obvious: The firefall simply attracted too many spectators, who brought too many cars and who left behind too much litter, automobile exhaust and trampled vegetation,” wrote Alfred Runte in “Yosemite: The Embattled Wilderness.” Thefts from the hotels and campgrounds, timed to coincide with firefall when visitors would be absent or distracted, were also on the rise. And, lastly, nearly every dead red fir tree accessible by road had been stripped of its bark for use as fuel.

Ultimately, park managers decided the artificial event must end. The 1963 report of the National Park Service’s (NPS) Leopold Committee on wildlife and ecosystem management, including fire ecology, heralded a new era of environmentalism. The findings eventually brought about two changes regarding fire in Yosemite: Suppression of natural wildfires in the park’s giant sequoia groves would cease, and so would the man-made fires sent careening nightly down the cliff face from Glacier Point.

A final ceremonial firefall was held on Jan. 25, 1968. A press release noted that, as it was winter, only about 50 people had gathered to mark the end of the tradition, which garnered both nostalgic and negative responses from park visitors. Russell Cahill, a ranger in Yosemite in the late 1960s, wrote the following reminiscence on a website that solicited memories from people who had seen the firefall. “After the firefall was stopped, all of the rangers and staff were required to answer the huge number of letters received from the public, many of which resembled the nostalgic memories of the people who have responded to this [website’s] request. I sat at my kitchen table at night writing responses to some pretty abusive letters.”

For a short time each February, when the setting sun hits Horsetail Falls at a precise angle, the cascade glows a brilliant orange, creating a natural "firefall." Credit: Krishna Santhanam, CC BY-ND 2.0.

The next winter, the Glacier Point Hotel was damaged by heavy snowfall and was still closed the following summer when, on July 10, 1969, an electrical fire broke out on the ground floor. McCauley’s Mountain House, which was then the oldest structure in the park but had been improved and was still in use as a café and employee housing, also burned, along with many trees. According to the NPS Structural Fire Management Program, “the pile of red fir bark left from the firefall next to the hotel added fuel to the fire.”

Although it’s been 50 years since an artificial firefall was last enjoyed in Yosemite, today there is a natural, even more awe-inspiring, phenomenon that goes by the same name. In mid-winter, when light from the setting sun hits Horsetail Falls on the east side of El Capitan at a precise angle, the cascade of water falling into the valley glows a brilliant, fiery orange.

First captured on film by Ansel Adams in 1940, it was popularized by National Geographic photographer Galen Rowell, who first photographed it in 1973, just five years after the artificial firefall ended. Now, for a few days each February, the fire falls once more.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.