by Bethany Augliere Friday, December 21, 2018

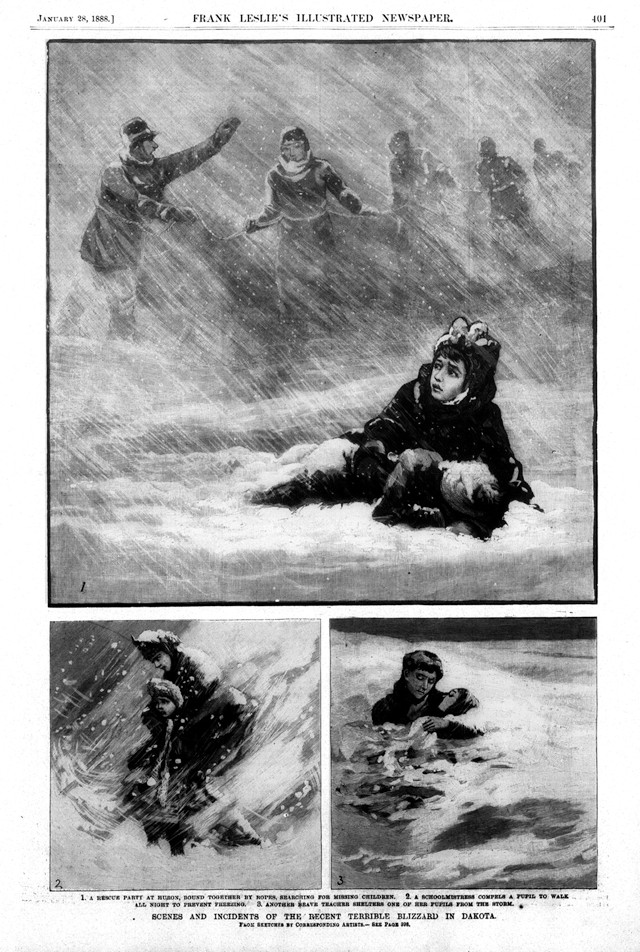

The Jan. 12, 1888, "Schoolchildren's Blizzard" swept across the Great Plains, killing at least 235 people — and possibly up to 500, according to some estimates — many of whom were children on their way home from school. Illustrations showing "Scenes and Incidents from the Recent Terrible Blizzard in Dakota" were published in the Jan. 28, 1888, edition of Frank Leslie's weekly newspaper. Credit: public domain.

By mid-January 1888, the Great Plains had seen ice storms, frigid temperatures and above-average snowfall. On the morning of Jan. 12, however, the weather was unseasonably warm and sunny, with temperatures reaching well above freezing in places. Many people, including children on their way to school, left home without winter coats, hats or mittens. In a matter of hours, everything changed.

Unbeknownst to them, a fast-moving Arctic cold front was racing toward the Great Plains about to unleash a blizzard unprecedented in recorded history. The storm rolled down from Canada over the Dakota Territories and Montana, Minnesota, Nebraska and Kansas before reaching as far south as Texas, where at least one river froze over with 30 centimeters of ice, according to an 1893 account.

In 24 hours, temperatures rapidly fell to subfreezing and winds gusted to more than 95 kilometers per hour, rattling doors and windows and even ripping roofs off buildings. Fine particles of snow and ice filled the air, which, combined with the low temperatures and howling winds, made breathing difficult, penetrated clothing and quickly froze extremities, including ears, nostrils and eyelids, of anyone caught out in the storm. At the time the storm reached eastern Nebraska and western Minnesota, children were preparing for dismissal time from school.

While some teachers attempted to protect their students and outlast the storm in their schoolhouses, some of which were one-room, sod-roofed structures ill-equipped to withstand the extreme conditions, others braved the whiteout conditions in search of other shelter as fuel to heat the schools ran out.

The storm lasted 12 to 18 hours and killed at least 235 people — and possibly up to 500, according to some estimates. Some bodies were not found for days, weeks or even months later when spring thaw arrived. The “Schoolchildren’s Blizzard” was one of the deadliest storms in American history due to a combination of unfortunate circumstances, including the time it struck and lack of warning from the Army Signal Corps, which at the time was tasked with national weather forecasting duties. The unusual weather event led, in part, to the creation of the United States Weather Bureau in 1890.

A blizzard is more than just a snowstorm. It’s defined by the National Weather Service as a storm lasting at least three hours with sustained winds or frequent gusts up to at least 56 kilometers per hour and heavy snow that reduces visibility to less than 400 meters. The 1888 blizzard was a “ground blizzard,” which doesn’t produce much snow but mobilizes snow on the ground to create whiteout conditions.

Accounts from survivors of the storm suggest that visibility was less than a meter. “You could hardly see your hand before you, or draw your breath and that with intense cold roaring wind and darkness it would appall the stoutest heart,” wrote one farmer who survived, according to the 2004 book “The Children’s Blizzard” by David Laskin.

Reports of people dying just meters from their homes, unable to find their way and lost amid the blowing snow, were common. Frank Bambas, a farmer in the Dakota Territory, uncovered his frozen wife while shoveling a path from his house to his barn. Others survived the night but later succumbed to their injuries, including cardiac arrest caused by shock, severe frostbite or infection.

Etta Shattuck, a 19-year-old schoolteacher from Minnesota, was found alive 78 hours after the storm struck, tucked into a haystack after she’d gotten lost. She died almost a month later from complications from surgery to remove her frostbitten feet and legs.

Blizzards occur more frequently in the northern plains of the central U.S. than anywhere else in the country, with the region spanning from the Front Range of Colorado to the Dakotas and east to Minnesota earning the nickname “Blizzard Alley.”

In a 2002 study, researchers analyzed blizzard occurrence by county across the Lower 48 states between 1959 and 2000. Trail County, in eastern North Dakota, saw the most recorded blizzards: 74. “Blizzards were most common in a ‘blizzard zone” of North Dakota, South Dakota and western Minnesota where each county had 41 or more blizzards in these 41 winters and the annual probability of a blizzard in each county exceeded 50 percent," the researchers wrote. In fact, 17 counties in North Dakota and eight counties in South Dakota had more than 60 blizzards during the study period.

Part of the reason this region sees more blizzards than other parts of the country is its relatively flat terrain, which is short on trees and broken only by small hills and streams. Strong, cold winds can rip southward from Canada across the northern plains with little to slow them.

Like many Great Plains blizzards, the 1888 storm began in western Canada where an enormous cold air mass had formed and began moving southeast out of Alberta. The temperatures ahead of the advancing low-pressure system warmed 20 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit (11 to 22 degrees Celsius). As the anticyclonic system moved south, it encountered warmer, moisture-laden air from the Gulf of Mexico.

“Out of nowhere, a soot-gray cloud appeared over the northwest horizon. The air grew still for a long, eerie measure, then the sky began to roar and a wall of ice blasted the prairie,” Laskin wrote.

The storm brought relentless, whipping winds, wind chills of minus 40 degrees in places and subfreezing temperatures that remained for days after the front moved through. Those caught out in the storm easily became disoriented in the whiteout conditions and many quickly suffered frostbite, suffocation and death.

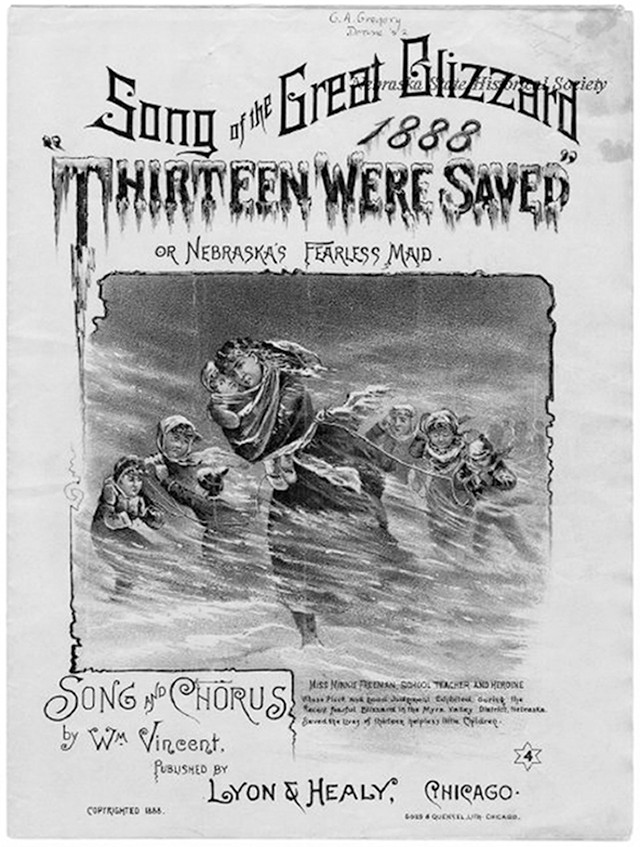

Minnie Freeman, a 19-year-old schoolteacher in Nebraska managed to get her pupils to safety during the blizzard, earning both local and national acclaim. A song was written about her called "Song of the Great Blizzard of 1888: Thirteen Were Saved" or "Nebraska's Fearless Maid." Credit: History Nebraska, Image 8731-50 (history.nebraska.gov).

As with many disasters, the news coverage immediately following the tragedy concerned the death and destruction: frozen children, blockaded trains, accounts of amputations, losses of livestock and the record cold temperatures. On Jan. 17, the New York Tribune reported the death toll at 145 and “growing every hour.” Stories about the storm remained on the front page for a full week. Two days later, the death toll stood at 217; by Jan. 21, it had reached 235.

It wasn’t until a Nebraska paper, the Omaha Daily Bee, ran a story on Jan. 18, 1888, that a different angle emerged: a tale of a young heroine. When the storm ripped off the roof of her schoolhouse, 19-year-old schoolteacher Minnie Freeman rescued her 13 students, the youngest just 6 years old, by tying them together with twine and leading them almost half a kilometer to safety at a nearby farmhouse in rural Mira Valley.

In an interview after the storm, she said: “I told them we would all have to stick together. If anyone was to stop to rub cold hands, all would stop. We went two by two, with strict orders to keep hold of the one just ahead,” according to an article in the Omaha World Herald. All the students survived.

For her act of heroism, Freeman earned both local and national attention. Lyon & Healy, a Chicago music house, published a song about her called “Song of the Great Blizzard of 1888: Thirteen Were Saved” or “Nebraska’s Fearless Maid.” She received more than 80 marriage proposals, all from men she had never met. The Nebraska State Education Board gave her a gold medal, and a wax bust of Freeman was exhibited across the nation.

The story of another heroine emerged in the aftermath of the storm, though, tragically, she was not as fortunate in her rescue efforts. Like Freeman, Lois Royce was also a teenage schoolteacher in Nebraska. She was trapped in her schoolhouse with three students — two 9-year-olds and a 6-year-old. When they ran out of heating fuel, she attempted to lead them to safety at her boarding house just 75 meters away. However, she became lost in the whiteout conditions. The children froze to death, and although Royce survived, her feet had to be amputated because of frostbite. Eventually, she learned to walk with artificial limbs.

In the 1940s, W.H. O'Gara compiled stories from a group of survivors who called themselves the Blizzard Club and published them in the book "In All Its Fury: A History of the Blizzard of January 12, 1888." Members of the club gathered in 1967 in front of one of the state roadside historical markers that commemorate the storm. Credit: History Nebraska, Image RG3139PH-152 (history.nebraska.gov).

The blizzard of 1888 left lasting impressions on survivors and the region. In 1940, W.H. O’Gara, Speaker of Nebraska’s House of Representatives and himself a blizzard survivor, suggested the state hold a dinner at the Lindell Hotel in Lincoln to pay tribute to the survivors. For decades afterward, people gathered on Jan. 12 to commemorate the storm. The assembled group, originally named the Greater Nebraska Blizzard Club, later became known as the January 12, 1888, Blizzard Club.

In 1947, O’Gara authored a book entitled “In All Its Fury: A History of the Blizzard of January 12, 1888,” which contained first-hand accounts of Blizzard Club members.

“The effects of disaster, no matter how extreme, do not last forever … Today, aside from a few fine marble headstones in country graveyards and the occasional roadside historical marker, not a trace of the blizzard of 1888 remains on the prairie,” Laskin wrote. “Yet in the imagination and identity of the region, the storm is as sharply etched as ever: This is a place where blizzards kill children on their way home from school.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.