by Sam Lemonick Wednesday, July 6, 2016

A bush fire burns near Steels Creek in Victoria on Feb. 7, 2009. Credit: ©Daniel Cleaveley, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported.

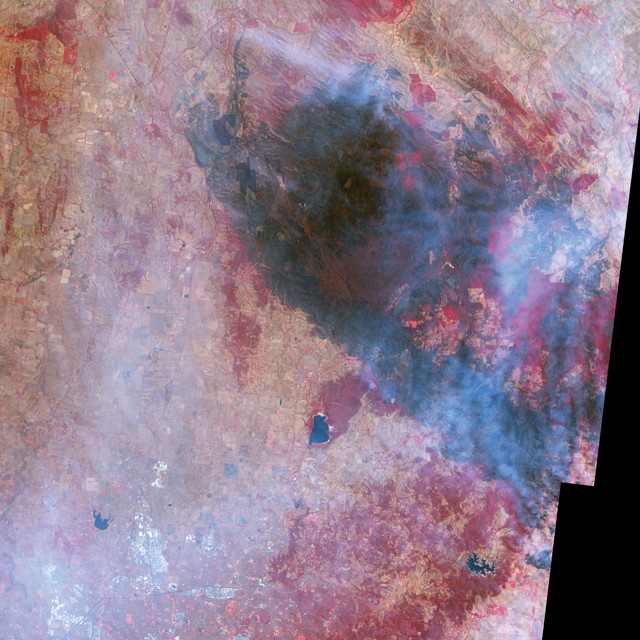

Fires were still burning a week after they started on Black Saturday in the Australian state of Victoria. Credit: NASA.

On Friday, Feb. 6, 2009, John Brumby, premier of the Australian state of Victoria, warned the public of the high risk of wildfires that weekend: “It’s just as bad a day as you can imagine and on top of that the state is just tinder-dry. People need to exercise real common sense tomorrow.” He was right. The next day, more than a dozen major fires and hundreds of smaller ones tore across the region, fueled by record temperatures and high winds. The so-called Black Saturday fires released more energy than 1,500 Hiroshima bombs, according to one fire expert. Together, the fires cost billions in damage and killed 173 people — the deadliest day of fires recorded in Australia.

As Victoria continued to heal, a Royal Commission investigating the fires released a report in 2010 recommending new regulations, safety procedures and practices to prevent fires and mitigate their effects. The commission also warned that growing populations and the warming climate will only increase the chance of deadly wildfires in the future.

A record heat wave starting in late January 2009 set the stage for Black Saturday. Temperatures in Victoria’s capital, Melbourne, topped 43 degrees Celsius three days in a row and on the day of the fire climbed higher than 46 degrees in places. CSIRO — the Australian government’s scientific research body — notes that the heat wave came on top of a 50-year warming trend and more than a decade of below-average rainfall, leading to intensely hot and dry conditions. Many weather stations in Victoria recorded zero rainfall through January. The Australian government warned that the region was the driest it had been since the Ash Wednesday wildfires in 1983, Australia’s deadliest fires before Black Saturday.

The 2009 heat wave was the result of a high-pressure system that moved into the Tasman Sea south of Victoria in late January and stayed there through the first week of February. The system pulled hot, dry air from central and northern Australia across Victoria. When the first fires started midday Saturday, winds were blowing 40 to 60 kilometers per hour from the northwest. As the day passed, a cold front moving in from the southwest brought wind gusts of 115 kilometers per hour and turned long, narrow fires that had been moving southeast into wide fires now racing northeast, destroying towns that earlier had been spared.

The scale of the fires was unprecedented, burning more than 4,000 square kilometers and destroying thousands of buildings. In places, flames reached more than 30 meters tall. Towering pyrocumulonimbus clouds created by the fires were kilometers tall and sent ash almost 20 kilometers into the atmosphere, higher than scientists had seen before. Wind carried embers 35 kilometers, lighting new fires far ahead of existing fire lines.

Most of the fires began burning before noon on Feb. 7. Downed power lines caused several of the major Black Saturday fires; as a result, the Royal Commission recommended in its 2010 report stricter regulations of power companies to avoid such downed lines in the future. Police suspect that still other fires were set deliberately. A fire in Bendigo, north of Melbourne, was started in the late afternoon by two teenagers who have since been charged with arson but were found unfit to stand trial. Another man was charged with setting the fire in Central Gippsland, to Melbourne’s east, which burned more than 245 square kilometers and killed 11 people. His trial begins this month.

Lake Mountain trail in Victoria about two months after the fires swept through. Credit: ©Peter Campbell, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported.

The largest and most destructive fire of the day was the Kinglake fire complex, formed when the Kilmore East fire and the Murrindindi fire merged and continued burning in an area about 60 kilometers northeast of Melbourne. Kilmore East was started by wind-downed electrical lines. Arson was long thought to be the cause of the Murrindindi fire, but police announced in June 2011 that they no longer thought the fire was deliberately set.

When the Kilmore East fire started burning, it quickly spread southeast ahead of strong winds. The fire had plenty of material to burn; weeks earlier, officers from the Country Fire Authority, which fights fires in rural Victoria, estimated the amount of burnable material in the area to be more than 4 million kilograms per square kilometer. According to the Royal Commission report, the officials were “horrified” to find so much burnable material and recognized that they “would be unable to control fire in these areas.”

Just before noon on Saturday, the Kilmore East fire was first reported in a field about five kilometers east of the town of Kilmore, 60 kilometers north of Melbourne. For the first two hours, firefighters working on the ground with water-pumping trucks and helicopters tried to keep the fire from jumping a highway about 10 kilometers southeast of Kilmore, but by 2 p.m., the fire had crossed the road. At that point the fire was long and narrow — an estimated three kilometers wide and 21 kilometers long — due to the strong northwesterly wind.

The day after Black Saturday, the hillsides of Yarra Ranges National Park were still smoldering. Credit: Nick Carson.

After the fire crossed the highway, the wind picked up, reaching 90 kilometers per hour at times. The fire entered the forested Kinglake National Park, where burning leaves and embers were blown ahead of the main fire line, spawning new fires more than 10 kilometers away. At 6 p.m., the wind changed direction as a cold front moved in. The fire also quickly changed direction and began moving northeast. The long flanks of the fire suddenly became the leading edge of the fire, and what had been a narrow fire was now dozens of kilometers wide.

This wide swath of wildfire destroyed many towns and villages that the fire had earlier missed. More than 1,200 houses were destroyed and 121 people were killed in this fire alone. One resident of Kinglake described being inside his house as the fire reached it: “Burning embers slapped into our windows and the rest of the house … it was like being inside a washing machine on full spin cycle, and full of fire and embers.”

Earlier that afternoon, 45 kilometers to the east of Kilmore, another fire started near the town of Murrindindi. It burned mostly through forests, where, like the Kilmore East fire, burning leaves allowed the fire to jump ahead of its fireline. Lightning from pyrocumulonimbus clouds also started new fires. Weather conditions prevented water-dumping airplanes from flying more than a couple runs, and ground crews had difficulty controlling the fire because of the many spot fires that cropped up.

Like the Kilmore East fire, the Murrindindi fire started out long and narrow but was pushed northeast by changing winds at about 6:30 p.m. Marysville, 75 kilometers northeast of Melbourne, was among the towns near the fireline when it changed directions. Embers reportedly began falling on the town about 6:50 p.m., and within an hour many houses had been consumed.

A house destroyed by the Kinglake fire. Credit: Nick Carson.

Premier John Brumby visited Marysville in the days after the fire and reported, “There’s no activity, there’s no people, there’s no buildings, there’s no birds, there’s no animals, everything’s just gone.” Only 14 of 400 buildings in Marysville survived. Thirty-eight people were killed in the Murrindindi fire, and in Marysville some of them were never identified because the extreme heat of the fire destroyed any forensic evidence. The next day, the Murrindindi fire and the Kilmore East fires merged and continued burning for almost a month.

One of the controversial aspects of Victoria’s wildfire policy that the Royal Commission investigated is what’s known as the “stay or go” policy. In effect, the decision to evacuate is left to residents and if they want to stay to protect their property, they are welcome to do so. Many Victorians have their own firefighting equipment and sprinkler systems to protect structures, but in many cases it wasn’t enough to protect against the fires of Black Saturday. In part, the policy is based on research that shows that it’s better to weather a wildfire in a house than in the open or in a car.

Nonetheless, the commission recommended that Victoria update its policy to include more education, such as noting that different fires carry different risks, and to strengthen building codes and prepare for earlier evacuations, especially of vulnerable residents. The commission also called for replacing old electrical equipment, like the downed wires that caused the Kilmore East fire, and for tighter regulations on the types of equipment power companies can use.

The commission also noted that climate change likely played a role in the size and number of the Black Saturday fires. High temperatures and low rainfall were produced by changes in weather patterns. A CSIRO report predicts by 2020 there will be longer fire seasons as a result of the warming trend and likely more days like Feb. 7, 2009.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.