by Timothy Oleson Friday, September 25, 2015

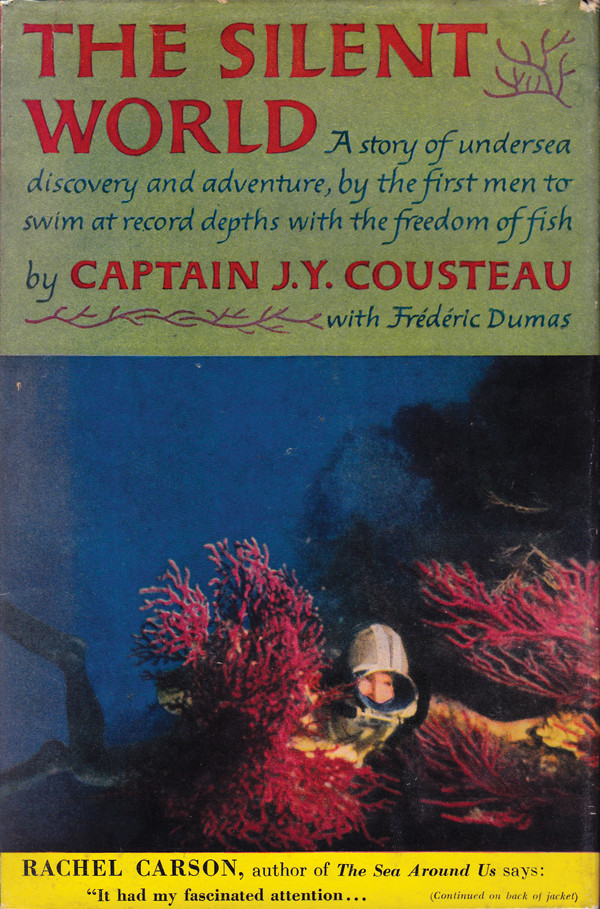

The Silent World. Credit: Captain J.Y. Cousteau with Frederic Dumas.

Few names are as evocative as Jacques Cousteau. The sunlight-infused blue glow of the marine subsurface, the endless array of otherworldly creatures that populate the ocean, and masked divers stealthily easing through the sea — trailed, of course, by glittering streams of bubbles emanating from Cousteau’s famed contraption — are morsels of the vivid imagery that his name often brings to mind. And with good reason: After all, he’s the one who introduced us to the real world below the waves, long before Bob Ballard found the Titanic or the Discovery Channel showed us what it’s like to swim with the sharks.

Developing the first self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (scuba) is undoubtedly Cousteau’s most lasting technical achievement. But what popularized his work and elevated him to celebrity and then legendary status were his adept and unceasing efforts to bring the wonderment of the undersea world to life on film and paper for the masses. These efforts began in earnest with the 1953 publication of his bestselling first book, “The Silent World,” which he wrote in English with his longtime diving companion, Frédéric Dumas.

In “The Silent World,” Cousteau and Dumas described the development of the “aqualung,” which allowed them to breathe easily and maneuver comfortably beneath the water’s surface for extended periods of time. They also detailed countless adventures and explorations that the new device let them pursue. (“At night I had often had visions of flying by extending my arms as wings,” Cousteau wrote. “Now I flew without wings.”) For many, the book was the first glimpse of what life underwater really looked like, displacing impressions forged by the fantastical portrayals by Victor Hugo in “Toilers of the Sea,” Jules Verne in “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” and others.

Jacques Cousteau's longtime research vessel, Calypso, arrives in the French port of Concarneau for restoration in 2007. Credit: ©Olivier Bernard, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported

Cousteau himself learned to dive at a young age by holding his breath, and by the time “The Silent World” was published, he’d already been experimenting with various underwater equipment — from masks and snorkels to oxygen re-breathers and compressed air apparatuses — for almost two decades. But aside from him, his dive team and the handful of intrepid recreational and military divers who had begun using his aqualung after 1943, when Cousteau first tested it, only a few people had experienced elements of the undersea realm in their native setting as of 1953.

“It is hard at this distance to know what a sensation he caused when he published the book,” writer Anthony Brandt pointed out in the introduction to the 2004 National Geographic Society reissue of the classic. Indeed, today we’re largely accustomed to seeing the marvels of the ocean up close, if not in person — with the help of compressed air tanks, a regulator and a pair of goggles — then on screen, courtesy of underwater cinematography (which Cousteau and his companions also pioneered and described in “The Silent World”). Nonetheless, Brandt noted in his introduction, perhaps the book’s popularity among readers at the time isn’t too difficult to comprehend:

President John F. Kennedy presents the National Geographic Society's Gold Medal to Cousteau outside the White House in 1961. Credit: courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

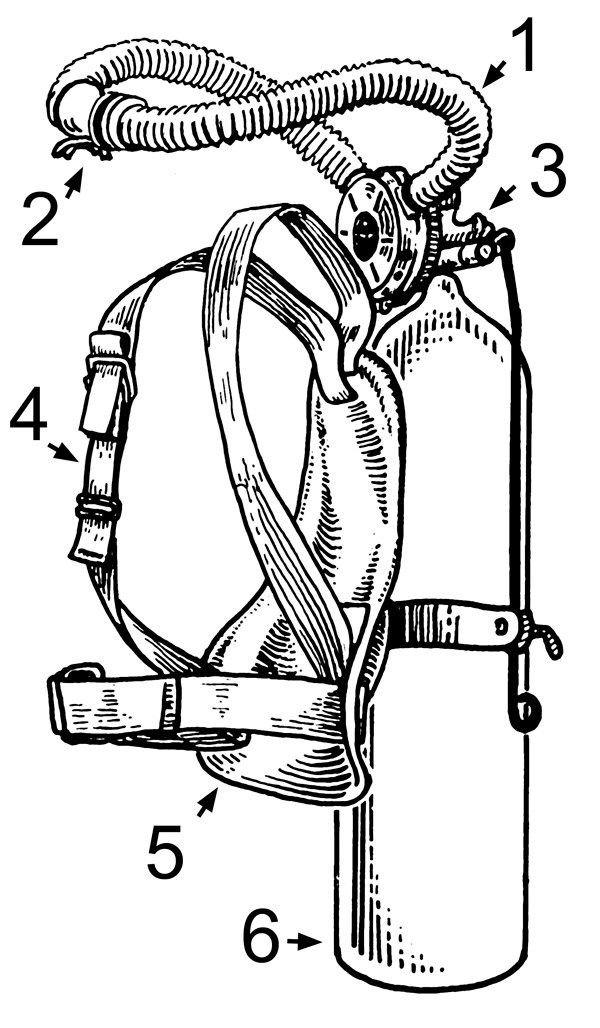

An artist's sketch of the original aqualung, consisting of an air hose (1), mouthpiece (2), air valve and regulator (3), harness (4), backplate (5) and compressed air tank(s) (6). Credit: Pearson Scott Foresman.

“Here for the first time men swim with dolphins and dance with octopi. They hitch rides on the fins of sharks and the tails of manta rays. From ancient wrecks in the Mediterranean they uncover the intricately carved capitals of marble columns and amphorae of wine still sealed after 2,000 years under the sea. … It is remarkable stuff, exciting and enlightening at the same time, and easy to read.”

Despite the perspective from 60 years on, it’s hard even today not to get swept up by Cousteau’s seemingly effortless courage and animated, though often clipped, brand of storytelling. Sometimes, he hurriedly jumps from one tale to the next, hitting the high notes of his team’s explorations courtesy of their newfound underwater breath and pausing only momentarily to reflect on near-death experiences or physiological insights gained. In the process, you, the reader, are left nearly without breath.

There was the time that Cousteau nearly perished while outfitted with an earlier diving apparatus consisting of a mask connected by a hose to a surface pump, which supplied air:

“I was enjoying the full breaths of the Fernez pump one day at forty feet when I felt a strange shock to my lungs. The rumble of exhaust bubbles stopped. Instantly I closed my glottis, sealing the remaining air in my lungs. I hauled on the air pipe and it came down without resistance … If I hadn’t instinctively shut the air valve in my throat the broken pipe would have fed me thin surface air and the water would have collapsed my lungs in the frightful ‘squeeze.'”

And there was the melee between Dumas, known as Didi, and a rather large fish — “a forty-pound individual” — he’d harpooned and was determined to wrestle to submission:

“The harpoon went through the merou. The big fish took off, towing Didi. It dived under the hull [of an undersea shipwreck], pulling Dumas into an unhealthy situation where his chest scraped the sand and his aqualung cylinders rang on the ponderous hull above … There was a furious fight in the dark, in sand clouds stirred up by the struggling bodies … and the fish gave him a fast ride through the winding maze to the open floor. It was a hard way to buy a fish, but we were hungry.”

At other times, Cousteau and Dumas take their time telling a story. But the descriptions are just as hair-raising, as in the case of their “worst experience in five thousand dives,” a treacherous descent into a deep, lightless freshwater cave that left them disoriented, delirious and barely able to find their way back to the surface.

For a mid-20th century audience, these and other remarkable experiences — their experimental excursions to depths beyond 60 meters or their close encounters with sharks, for example — must have been almost unfathomable, like science fiction come to life. The book is all the more engaging thanks to Cousteau’s ability to pull you in as if you were hovering in the water beside him.

In a 1956 New York Times review of Cousteau’s first film, also named “The Silent World” but largely composed of footage shot after the book’s release, reviewer Bosley Crowther wrote that “with a sense of the awesome and the dramatic as well as with technical skill … Captain Cousteau and his team of skin-divers have produced a marine adventure film that combines the experience of looking at marvels with a wonderful intimacy.”

The sentiment also holds true for the book, which sold 5 million copies worldwide upon its release, according to Brandt. In the end, the movie, which won the Palme d’Or at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival as well as an Academy Award, may have done even more to bring the beauty and fate of the underwater realm to a wider audience. But the book’s popularity no doubt buoyed Cousteau’s efforts and set the stage for the film. Together, they kick-started a recreational diving craze. As Brandt wrote, “by 1960 a million Americans were diving with scuba gear. The manufacturers could not keep up with the demand.”

After “The Silent World,” Cousteau went on to write more than 40 additional books and produce more than 100 films for the big screen and television. He received numerous awards and honors, including the National Geographic Society’s Gold Medal in 1961, and he was named a commander in the French Legion of Honour in 1972. He headed the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco and founded the nonprofit conservation societies, the Cousteau Society and Equipe Cousteau. And until his death in 1997, he continued plumbing the depths of underwater environments and experimenting with the aid of his aqualung, early submersible research vehicles and manned seafloor habitats, no doubt inspiring — both intellectually and creatively — the many explorers who would follow him beneath the waves.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.