by Bethany Augliere Wednesday, November 30, 2016

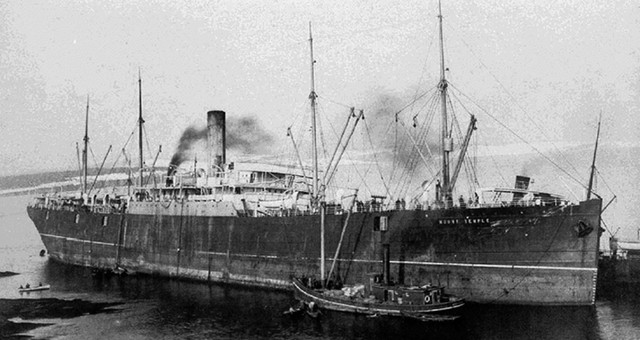

The SS Mount Temple in Nova Scotia in 1907, nine years before its fateful journey. Credit: public domain

One hundred years ago this month, a Canadian cargo ship — the SS Mount Temple — departed the port of Montreal on the St. Lawrence River headed for France. On board were 3,000 tons of wheat, more than 700 horses bound for service in World War I, and an unknown number of 75-million-year-old dinosaur skeletons and bones destined for the British Museum of Natural History. But the ship, and the fossils, never made it.

On Dec. 6, 1916, a German surface raider, the SMS Möwe, attacked and sunk the Mount Temple about 900 kilometers northwest of the Azores, sending it to seafloor 4,725 meters below, where it still lies today.

“There are not many dinosaurs that have been lost at sea, and there have been fewer lost in military action,” says Darren Tanke, a paleontological lab technician at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in Alberta, Canada.

The fossils were excavated from what is now Dinosaur Provincial Park (DPP), a UNESCO World Heritage site in southern Alberta, about 220 kilometers east of Calgary. The 80 square kilometers of Late Cretaceous badlands contain fossils from about 44 species of dinosaurs and 150 total vertebrate species, ranging from ancient turtles to pterosaurs to mammals, including some of the most important fossil discoveries ever made. “It’s probably the richest single area in the world for dinosaur remains,” Tanke says.

Tanke first learned about the sunken fossils as a boy, while reading the 1968 book “Men and Dinosaurs: The Search in Field and Laboratory” by American paleontologist Edwin H. Colbert. Years later, Tanke would help discover a lost quarry from which some of the Mount Temple specimens had been excavated by the famous American fossil-hunting family, the Sternbergs. That discovery also helped Tanke uncover a long-held misconception about the ship that attacked the Mount Temple.

In 1916, Charles H. Sternberg, an amateur paleontologist from Kansas and veteran of the late 19th-century Bone Wars, spent the summer in Alberta gathering bones for the British Museum of Natural History. With him was the youngest of his three sons who had joined him in the family business, 22-year-old Levi. The museum was interested in building its dinosaur collection for research. In particular, Sternberg was exploring a region then called the Belly River Formation (now the Dinosaur Park Formation), an 80-meter-thick sequence of exposed sandstone and mudstone strata.

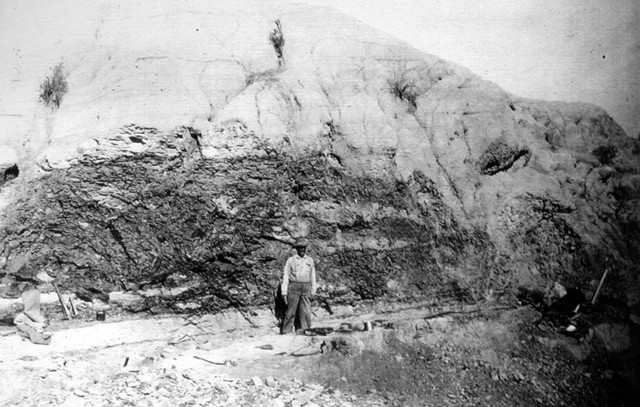

A 1916 photo of one of the lost Sternberg quarries, which was recently rediscovered. Credit: Charles H. Sternberg, "Hunting Dinosaurs in the Bad Lands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada," 1917.

During the Cretaceous, this landscape was sprinkled with ponds and swamps and cut by a deep, snaking river. The region is now filled with skeletons and bones of hadrosaurs and marsh-loving reptiles. While on the 1916 dig, Sternberg penned letters back to England weekly describing his findings. “We have hundreds of bones already collected and many more located,” Sternberg wrote from the field on June 26, 1916. “I am making a clean sweep and you will get thousands of good bones representing the whole Belly River Serries (sic), you will be able to restore limbs and feet of many species without the trouble of digging them out of the rock.”

This photo of fieldwork at Dinosaur Provincial Park (DPP) was found loose at the park decades ago. Credit: courtesy of Dinosaur Provincial Park.

Royal Tyrrell Museum fieldwork at DPP. Credit: courtesy of Royal Tyrrell Museum.

That summer, one shipment of fossils successfully made it across the Atlantic to the British Museum. The second, however, consisting of at least 22 wooden crates filled with bones still encased in rock and wrapped first in newspaper, and then in their thick plaster field jackets, was aboard the Mount Temple.

DPP is one of the richest fossil sites in the world and contains the remains of Champsosaurus, a thin-snouted crocodile-like reptile. The site was established as a UNESCO World Heritage Site on Oct. 26, 1979. Credit: Paul Gorbould.

Based on Sternberg’s letters and other research, it is likely that the crates contained four partial duck-billed dinosaur skeletons, including a Parasaurolophus — the hadrosaur adorned with a long, plume-like crest atop its skull. Some of these hadrosaurs may have also had preserved skin impressions, Tanke says. The shipment likely also included several turtles, including a rare ancient freshwater turtle, and most of the bones of a small aquatic reptile called Champsosaurus, which resembles a modern gavial, a thin-snouted crocodile. Finding isolated parts of the Champsosaurus is common in DPP, Tanke says, but full skeletons are rare. “So, some of the specimens were quite important, but the others, we can find more of them,” he says.

The SMS Möwe, which means “seagull” in German, was not always a surface raider — a militarized ship that prowled the open sea disguised as a merchant ship, which attacked British merchant shipping. In 1914, it launched from Germany as the Pungo to haul bananas from Kamarun (German Cameroon, then a German protectorate). However, when the war broke out, it was converted to a surface raider. The German strategy was to starve England of her imports, leaving the island country to slowly wither, forcing a surrender.

On Dec. 6, 1916, the Mount Temple was intercepted by the Möwe. The captain of the Möwe approached the Mount Temple and signaled it to stop and surrender, Tanke says. But instead of surrendering, someone on board ran to the deck gun mounted on the stern and pointed it at the Möwe.

The Germans fired at the Mount Temple, killing three of the crew and wounding several others. “I don’t think the Mount Temple got any shots off at all. The Germans shelled the Mount Temple into submission,” Tanke says. Then, the Möwe crew took rowboats to board the Mount Temple, and brought back the roughly 100 survivors, who were then sent to Germany as prisoners.

The Germans opened all the hatches and portholes, and planted demolition charges below the waterline. Upon detonation, the Mount Temple rolled over and sank, with the dinosaur bones, and horses, still aboard.

The paleontology literature had indicated that the fossils that went down with the Temple had been quarried from two sites. Those sites had been marked in the 1930s with steel markers set in concrete to identify what was there and when it was excavated. “But they only marked sites they thought were important,” Tanke says.

In summer 2001, Tanke — who has spent part of his career identifying “unimportant,” lost, or unmarked quarry sites, 35 in the DPP alone — was giving a talk about these discoveries at the Royal Tyrrell, in which he described how he often identified one of these sites by finding a piece of old newspaper. “I said in the talk, ‘if you ever find newspaper, don’t touch it! Come and get me.'”

Visitors to DPP can take guided tours to view historic quarry sites and hike to dinosaur fossil bonebeds. Credit: both: Paul Gorbould.

Later in the week, Tanke was at a dig site in the badlands collecting bones with students visiting from Norway, Nicolai L. Hernes and Tom E. Guldberg, who had attended the talk. Tanke was uncovering a turtle fossil when he heard one of the students yell, “I found newspaper!” Some sleuthing revealed the scrap of newspaper to be an advertisement from Yonge Street, a famous street in Toronto, “so I knew it was a Canadian-based dig,” he says. With the help of a friend, Tanke was then able to date it by a microfilm search and found a match to The Evening Telegram for Thursday, June 8, 1916. Levi Sternberg’s fiancée lived in Toronto. This led Tanke to conclude it was one of Sternberg’s 1916 dig sites at which his son had helped. But was it a source of the Mount Temple dinos?

Although Tanke had never before seen the quarry in which the piece of newspaper was found, it seemed familiar to him and he soon realized he had seen the quarry in Sternberg’s book “Hunting Dinosaurs in the Bad Lands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada,” which was published soon after the Mount Temple sinking. Tanke relocated in the book an image of the quarry, taken in 1916. In the caption, it referred to the site as being a location for a Mount Temple hadrosaur quarry. Tanke and the students had discovered a third site.

The original records indicated that the Mount Temple had two hadrosaurs on board from two quarries. With the discovery of a third site, this meant three hadrosaurs, Tanke says. So, he says, he started wondering what else might have been on board. As he explored more about the Mount Temple, trying to determine what fossils were aboard, he discovered an “astonishing story,” he says.

DPP contains a mixture of riparian habitat and Late Cretaceous badlands and is home to fossils from more than 44 species of dinosaurs, dating back 75 million to 77 million years. Credit: Paul Gorbould.

Prior to his research, the paleontological literature had reported that a German U-boat sank the Mount Temple, because that is what Sternberg had written in his 1917 book about the loss of the shipment. But after digging through historical records, Tanke discovered it was instead sunk by the raider Möwe. Near the end of World War II, the Möwe — which sank about 50 vessels in the two world wars — met its own violent end. On April 7, 1945, the ship, then renamed the Oldenburg, was moored in the harbor of Vadheim, Norway, where it was armed to support the German occupation, when Allied aircraft sunk it.

Darren Tanke and his colleagues visited the site in Norway where the SMS Möwe, which sank the Mount Temple in World War I, was itself sunk during World War II. Credit: Darren Tanke.

In 2005, Tanke went with a team to visit the site in Norway. “I got to sit on the spot where the ship that sank the Mount Temple was itself then sunk in World War II,” Tanke says. The spot, coincidentally, was less than 60 kilometers from where the two Norwegian students grew up. Others from the crew dove the wreck.

No similar attempt has been made to discover the resting place of the Mount Temple, as it lies in much deeper water. But Tanke says he hopes that one day it will be searched for and found. The World War I logbooks of the Möwe contained latitude and longitude coordinates of the sinking to the nearest kilometer, and deep-sea submersible technology has advanced, he says.

The Mount Temple rolled to her side when she sank, which means the loose cargo in the holds would’ve fallen out, Tanke says. Though some of the dinosaur bones would’ve dissolved by now, some of them might still be down there. Small fossils, such as teeth, could be in perfect condition, if stored in sealed bottles, which have been found at Sternberg’s quarries. And because sedimentation is slow in pelagic deep ocean basins like the one where the Mount Temple sunk — on the order of 2 to 5 centimeters per 1,000 years — the fossils should still be visible, Tanke says. “It is just a matter of money, and having the gumption to go look for them.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.