by David B. Williams Monday, June 20, 2016

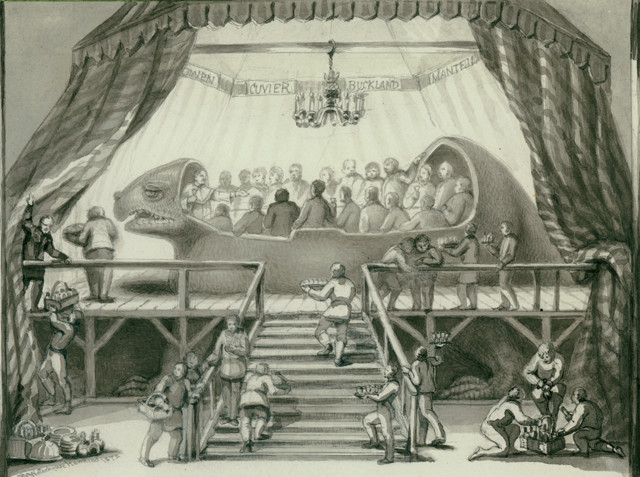

On New Year's Eve, 1853, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins hosted a formal dinner in the mold of an Iguanodon. Credit: Academy of Natural Sciences, Ewell Sale Stewart Library and the Albert M. Greenfield Digital Imaging Center for Collections.

The weather in London on Saturday, Dec. 31, 1853, could not have pleased Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. After a relatively warm Friday, the temperature had plummeted, snow had begun to fall, and for the first time in more than a decade, masses of ice floated down the Thames River. The snow made the streets so slippery that injured pedestrians filled the hospitals.

For New Year’s Eve, Hawkins was hosting an elaborate feast at his sculpting studio in Sydenham, 11 kilometers south of London. Would his guests be able to find transportation out to Sydenham and then across the pastures of muddy swamp that surrounded the wooden building where the dinner would be held? Hawkins hoped so; he had been planning the meal for more than a month. It would be the first time that most of his dinner-mates had seen the incredible life-sized dinosaurs that he was building for the Crystal Palace Exhibition, which Queen Victoria and Prince Albert would open to the public in June. The previous year, a group of investors had bought the Crystal Palace, an ornate cast-iron and glass edifice that had housed the Great Exhibition of 1851 (London’s first World’s Fair). The investors moved the building to Sydenham, where they planned to celebrate the “triumphs of industry and art,” and hired Hawkins to direct the “Fossil Department.” They tasked him with populating a vast geologic display with giant monsters of the ancient world, including the first three dinosaurs ever described: Megalosaurus, Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus.

Hawkins was uniquely qualified to bring these great animals to life. He had initially achieved fame for his detailed illustrations of animals collected by British explorers, including the still relatively obscure naturalist Charles Darwin. Subsequently, Hawkins started to sculpt, and to write and illustrate books on animal anatomy. For his efforts in taking new scientific findings and translating them into words and images accessible to the general public, Hawkins earned membership into the most exclusive science clubs of the era — the Royal Society, the Geologic Society of London and the Linnean Society.

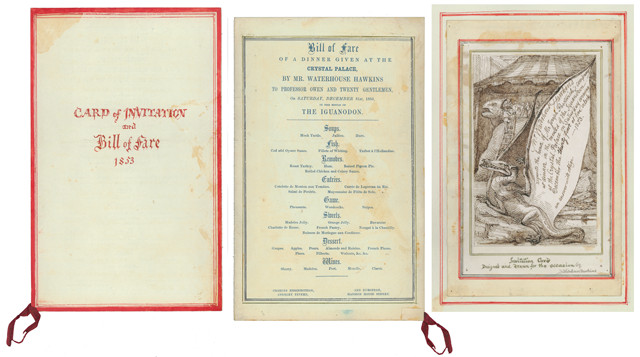

In early December 1853, Hawkins sent out invitations for his New Year’s Eve bash. For one guest, he sketched the profile of the giant herbivorous Iguanodon with a feast table in its body. In front of it, he added a Pterodactyl, its mouth filled with pointed teeth. For another guest, he turned the Iguanodon to face the viewer with the table still inside the body. In the foreground, a wine-sipping participant rides the neck of a Plesiosaur, on which stands a Pterodactyl. On both cards, Hawkins carefully penned on the Pterodactyl’s outstretched wing “Mr. Waterhouse Hawkins requests the honor of ——–’s company at dinner in the mould of the Iguanodon at the Crystal Palace on Saturday evening December the thirty first 1853 at five o’clock. An answer will oblige.”

Hawkins hand-drew the invitations to his dinner in an Iguanodon. Twenty prominent men accepted the invitation. Credit: All: Academy of Natural Sciences, Ewell Sale Stewart Library and the Albert M. Greenfi eld Digital Imaging Center for Collections.

Hawkins chose his guests carefully. They included Richard Owen, Hawkins’ scientific adviser and the man who coined the term dinosaur in 1842; Francis Fuller, the managing director of the Crystal Palace; Edward Forbes, a jovial, irreverent paleontologist who mentored Thomas Huxley and advised Darwin; Joseph Prestwich, winner of the Geological Society of London’s highest award, the Wollaston Medal, and a man well-liked for his propensity to end geology walks at vineyards; and ornithologist John Gould, who in 1837, identified the finches collected by Darwin on the Galapagos. Because Hawkins viewed the feast as a publicity stunt, he also invited Herbert Ingram, publisher of The Illustrated London News, a paper with a circulation of more than 150,000.

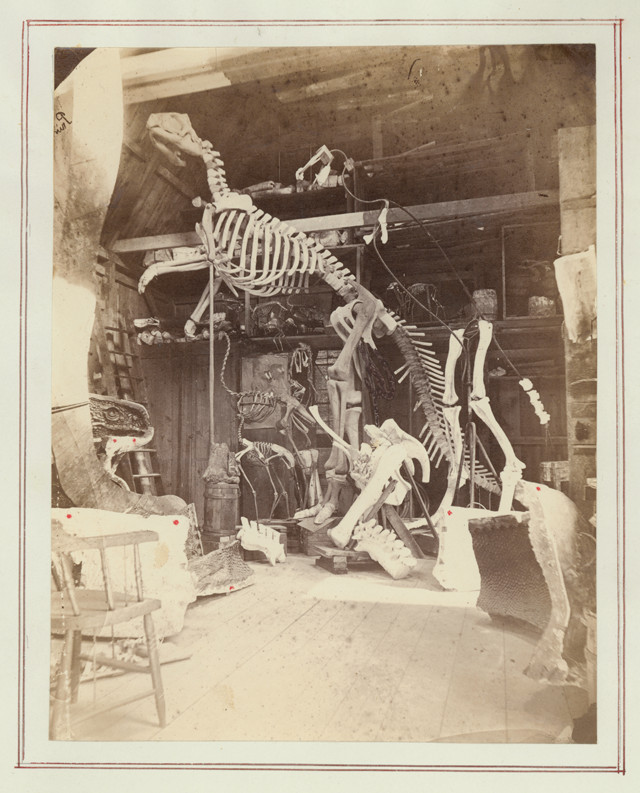

Twenty men accepted the invitation. Despite the snow and ice, they donned formal attire and traveled by train from London and tromped to Hawkins’ studio. Inside the large warehouse, the men found an unimaginable menagerie of creatures sculpted by Hawkins. Largest was the Hylaeosaurus, with thick stippled skin and a single row of spikes down its back. Near it rested an amphibian known as a Labyrinthodon and a curious beast that looked like a turtle with a pair of tusk-like teeth. In another corner, a tapir-like Paleotherium poked its head out from under a wooden scaffold.

To reach their dining table inside the Iguanodon mold, the guests ascended a short flight of steps to a platform built around the massive model. Above them rose a pink and white tent, which helped keep out the cold wind that snuck in through the wooden walls of the building. Additional heat and light came from a crystal chandelier and brass candelabras. For the final touch, Hawkins hung banners bearing the names of the paleontologists who had pioneered the study of dinosaurs: Georges Cuvier, Gideon Mantell, William Conybeare and William Buckland.

Each guest had an assigned seat at the table inside the body of the Iguanodon. Owen had the presiding seat, tucked into a nook formed by the dinosaur’s head. In the roomier rear end sat Fuller and Forbes and a musician “whose delightful singing greatly increased the pleasure of the evening,” Hawkins wrote in a description of the night in 1872. Hawkins placed his friends Prestwich and Gould on either side of him and filled in the sides with the rest of the men. Certainly no other dining table in England was so unusual nor held such an esteemed group. A team of liveried servants brought in the food — a trio of soups, three varieties each of fish and fowl, a quartet of meats and luscious sweets — and copious amounts of wine on silver platters.

Hawkins' studio circa 1869. Credit: Academy of Natural Sciences, Ewell Sale Stewart Library and the Albert M. Greenfi eld Digital Imaging Center for Collections.

The conversations, especially ones lubricated by generous glasses of wine, must have been vivid. They probably discussed Mantell’s recent death (was it a suicidal drug overdose or an accident?), Buckland’s erratic slipping into dementia and those young upstarts Darwin and Huxley (both of whom had just won the prestigious Royal Medal). And what did the royal couple say when they visited Hawkins’ studio in November? Fossils may also have come up a time or two. Eventually, Owen asserted his role at the head of the dinosaur table and offered a round of toasts. Finally, around midnight, Forbes stood before the group, noting that he was indebted to Mr. Waterhouse Hawkins for providing the opportunity to spend the evening in “an antediluvian dragon.” He then launched into an elaborate poem.

A thousand ages underground

His skeleton had lain;

But now his body’s big and round,

And he’s himself again!

Beneath his hide he’s got inside

The souls of living men,

Who dare our Saurian now deride

With life in him again?

Encouraging the revelers to join him, Forbes offered a chorus.

The jolly old beast

Is not deceased,

There’s life in him again. (A roar.)

As Forbes continued through his verses, the men became “so fierce and enthusiastic, as almost to lead to the belief that a herd of iguanodons were bellowing,” as described in “Routledge’s Guide to the Crystal Palace and Park at Sydenham.” Eventually the roaring ended, the men climbed out of the Iguanodon, fumbled past the other beasts, donned their overcoats, and made their ways back through the cold to the train station and returned to London. It was “a good wind-up for a geologist’s year,” Forbes is quoted as saying in Archibald Geikie’s “Memoir of Edward Forbes.”

As Hawkins hoped, his New Year’s Eve publicity stunt fostered keen interest in what The Times of London described as the “gigantic tenants of … the earliest and sublimist pages in the history of creation.” Charles Dickens mentioned the meal in his newspaper, and Herbert Ingram, in The Illustrated London News, concluded that the guests were “evidently well pleased with the modern hospitality of the Iguanodon, whose ancient sides there is no reason to suppose had ever before been shaken with philosophic mirth.”

Six months later, more than 40,000 people attended the opening of the Crystal Palace and saw Hawkins’ beasts. His dinosaurs quickly became icons of Victorian England, launching the world’s first wave of dinomania.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.