by David B. Williams Thursday, November 19, 2015

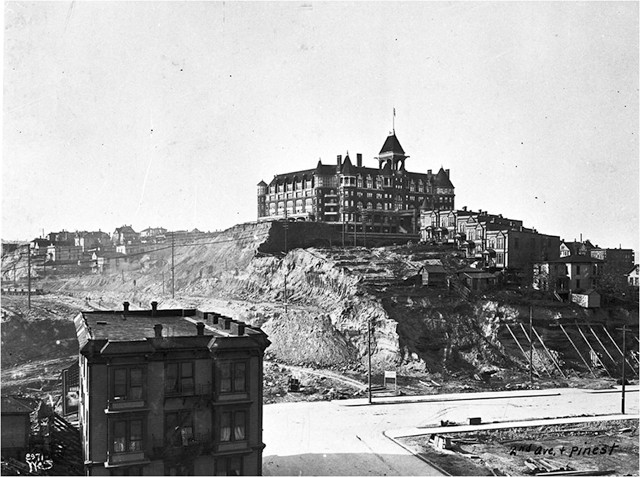

The Washington Hotel in 1905 during the regrade of Second Avenue. Within three years, the hotel and the hill under it had been removed. Credit: courtesy of Seattle Municipal Archives, Image 77282.

Few cities in the United States can rival Seattle for the scale of reengineering to its landscape. Not only did its citizens make more than 890 hectares of new land in its harbor, but they also replumbed the city’s largest lake, completely changing its drainage pattern and drying up its main outlet, and regraded tens of millions of cubic meters of its hills. The most famous of these projects was the elimination of Denny Hill, a 73-meter-high hill that stood at the north end of Seattle’s central business district.

After more than three decades of work, the regrading of Denny Hill was completed in December 1930. “That once great promontory, thrown up by nature ages ago to make trouble for Seattle’s progressive expansion,” was now gone, wrote a Seattle Times reporter at the time. “At last the way was opened for giant new buildings, for the forward sweep of the central business district northward on level grades into territory which only a few months ago barred progress with a lofty barricade of clay banks, ill-kept streets, run-down residences, aged public and semipublic structures.”

The regrading of Denny Hill was driven primarily by Seattle city engineer Reginald H. Thomson, a man who had little regard for the city’s notorious topography. To Thomson, Seattle “was in a pit, that to get anywhere we would be compelled to climb out if we could.” Hills such as Denny stifled progress, restricted transportation, and lowered property values. If Seattle was going to be great, it had to remove its hills, and Thomson decided he was the man to do it.

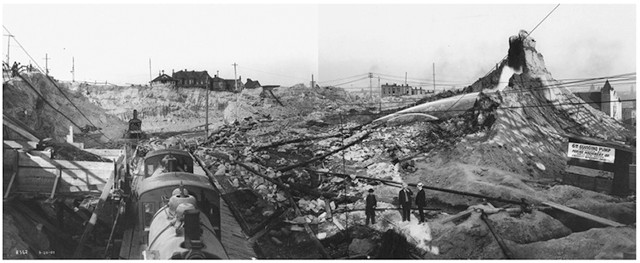

The Denny Hill project, shown in 1907, involved trains, steam shovels, hydraulic cannons, thousands of meters of piping and tons of debris. Credit: courtesy of UW Special Collections, Image UW36359, composite image from photos by Asahel Curtis.

Thomson’s first push came in March 1898 when work began on the west side of Denny Hill. Using hydraulic hoses, workers washed away 13 blocks of First Avenue. The deepest vertical cut was 5 meters. Most of the resulting 85,000 cubic meters of sediment ended up in nearby Elliott Bay.

Five years later, Thomson’s crews attacked the hill again. The Second Avenue regrade removed more than 450,000 cubic meters of material, nearly all of which went into Elliott Bay. At least three people died during the project, including a 9-year-old boy who was killed by dynamite that a worker was warming in a pan over an open flame. Thomson’s third regrade project began just a few months later and focused on the hill’s south end. This was one of Denny Hill’s two summits and had its steepest slope, which rose 30 meters in one block. It was also the location of one of Seattle’s grandest buildings, the Washington Hotel. Opened in 1903 — its first guest was President Theodore Roosevelt — the hotel offered spectacular views of the city, Puget Sound and the surrounding mountains. Its owner had battled Thomson for months over the regrading project but finally acquiesced; he realized that razing his hotel and lowering the hill would significantly raise the value of his land. By 1908, another 500,000 cubic meters of Denny was gone and so was the hotel.

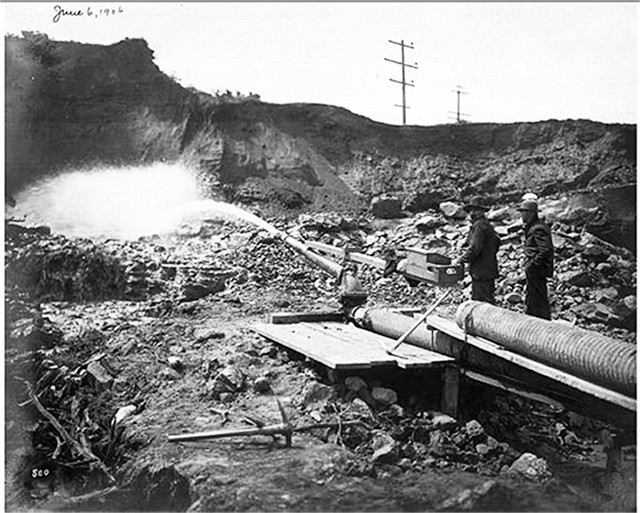

High water pressure was achieved by pumps or by gravity feed, sending the water down hill through sequentially smaller pipes. Credit: courtesy of UW Special Collections, Image UW36352.

What made regrades possible in Seattle was the city’s glacial past. During the last glacial maximum, the 1,000-meter-thick Puget lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet passed over and through Seattle, eventually reaching Olympia about 70 kilometers to the south. The glacier left behind three distinct layers of material, which compose Seattle’s hills. At the base are fine-grained clays deposited in a proglacial lake. Within this layer are boulders up to 3 meters in diameter. That base layer is covered by a layer of outwash sand, and then there’s a thin layer of till at the top. Although the glacial advance did compress and consolidate these sediments, the clay and sand are relatively soft and easily removed.

For most of the regrades in Seattle, the primary means of removal was hydraulic force. This required vast quantities of water, most of which was pumped from Elliott Bay or Lake Union, just north of Denny Hill. Pipes from the water sources fed into pits where workers operated the hydraulic hoses, known as “giants.” Each pit had two giants and a five-man team. One man fired each giant, holding a meter-long handle connected to a cast iron nozzle. The 2- to 3-meter-long nozzle sat on an articulated base and had an adjustable opening from 7 to 12 centimeters in diameter. This was the most highly skilled position on the team and was often filled by “old giant [men]” who had learned their trade in Alaska’s gold fields. In addition, each giant team used boards to direct the muddy slurry in the pit to a pipe that carried away the former hills. The boardman also removed roots and other material that could choke the system. Another man monitored the iron bars, or grizzly, at the mouth of the pipe, which kept out larger rocks and lumps of clay. He, too, removed or sledgehammered the larger material into smaller bits. Under normal conditions, a crew could wash away about 750 cubic meters of material in an eight-hour shift, or enough material to fill 6,750 wheelbarrows.

Water generally provided enough force to dislodge the hill, but when the workers hit hard lenses in the clay and till, or came across boulders, they had to rely on dynamite. More exciting was when workers found fossils, including tree trunks and mammoth teeth.

Isolated buttes known as "spite mounds" — shown in 1910 — were left around the city, allegedly because their owners didn't agree with the regrade and left them high to spite the city. Credit: courtesy of UW Special Collections, Image UW4812.

Thomson might have considered the first three regrades practice sessions. In August 1908, he had his workers turn their hydraulic guns onto the heart of the hill. Working constantly over the next two and a half years, they would wash more than 4.1 million cubic meters of dirt into the bay. This fourth effort produced what is perhaps the most famous feature of the regrades: the isolated buttes known as “spite mounds,” “spite heaps” or “spite humps.” In May 1910, six of these notorious pillars of private property rose above the flattened surface of the hill, giving the regrade the appearance of Monument Valley.

Legend holds that they existed because their owners supposedly didn’t agree with the regrade and left them high to spite the city. There is no evidence, however, to back this claim. At least three of the people who owned the mounds signed petitions for the regrades. In addition, two of them spoke with reporters at the time, both stating their full support for the regrades. One said he had left his mound standing because he didn’t have money at the time to pay for it, and the other owner was in Alaska. As soon as he arrived in Seattle, he paid to have his mounds leveled.

The fifth and final regrade of Denny Hill began in May 1929. For the first time, workers did not use hydraulic giants. Too much of the area surrounding the regrade had been developed, so funneling a muddy stream across heavily trafficked paved streets was not practical. Instead, the contractor removed the hill with power shovels, or excavators, and as had happened in all previous regrades, the dirt went into Elliott Bay. To reach the bay, the sediment was transported by conveyor belt out to self-tipping barges.

Self-tipping barges had two internal tanks, one on each side, and open decks that held 300 cubic meters of dirt. A tug towed the full scow out into Elliott Bay, where a crewmember opened valves on one side of the boat. Within minutes, water filled one of the tanks, and the out-of-balance scow flipped over, dumping its load. The tug then pulled the scow back to shore, ready for its next load.

Chunk after chunk of the hill was fed into the hoppers, dropped onto the ever-moving conveyor belts, and shot along at 120 meters per minute to the waiting scows and into Elliott Bay. The crews were unrelenting. By December 1930, Denny Hill was almost gone.

On Dec. 10, Mayor Frank Edwards climbed into one of the excavators, pulled a lever, and the final cubic meters of Denny Hill vanished. Hundreds of people stood by, including many who had been born on the hill, had attended Denny School and had lived there their whole lives. “There were many moist eyes,” wrote a reporter for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

In 1988, during an examination of the bathymetry of Elliott Bay, University of Washington oceanographer Mark Holmes and his colleagues noticed an anomalous landform just offshore of downtown Seattle. Unsure why it was there, they measured the small mound via a seismic reflection survey and found that it ranged between 3 and 36 meters thick and measured 460 meters wide by 760 meters long. Total volume was about 6.8 million cubic meters. When Holmes and his team began to research the history of Elliott Bay, they realized that they had stumbled across the remains of Denny Hill. It was right where it was supposed to be, long forgotten, but not gone.

This article was adapted from Williams’ latest book, “Too High & Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography,” published this fall. More of his work can be found at geologywriter.com.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.