by Sara E. Pratt Monday, December 15, 2014

©Shutterstock.com/Zack Frank.

Long before Los Angeles’ infamous traffic packed the pavement of Wilshire Boulevard, the area teemed with hundreds of species of Ice Age animals that became trapped in an asphalt quagmire of a different sort: the La Brea tar pits.

Today, Rancho La Brea, as the site is officially named, lies along Wilshire in the heart of downtown Los Angeles. Although colloquially called “tar,” the gooey, black substance that seeps from underground at a rate of 32 to 48 liters per day is actually naturally occurring asphalt, which, for at least the last 50,000 years, has been bubbling up, along with methane, through faulted sedimentary beds from the Miocene-aged Salt Lake oilfield that underlies the pits.

The asphalt also seeps into bones and teeth, preserving them exceptionally well, which is what makes Rancho La Brea one of the most valuable Pleistocene paleontological sites in the world. Since excavations began in the early 20th century, millions of fossils representing more than 565 species have been recovered, including many of the large extinct mammals that fascinate museum-goers today: mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed cats, American lions, Western camels and horses, ground sloths, short-faced bears and dire wolves.

The remains of only one human have ever been recovered from the pits, when a skull and partial skeleton were discovered in 1914. Anthropological analysis revealed they belonged to a 20-year-old woman, now called La Brea Woman, who lived 9,000 years ago and possibly died from a blow to the head.

The earliest recorded description of Rancho La Brea occurred in August 1769, when a Spanish expedition scouting the area that would become El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles came across unusual water- and asphalt-filled pools. In his diary entry of Aug. 3, Juan Crespi, a Franciscan friar with the expedition of Gaspar de Portola (the first Spanish governor of the region that is now California), described “muchas pantanos de brea,” or extensive bogs of tar. “We proceeded for three hours on a good road; to the right were extensive swamps of bitumen which is called chapapote,” Crespi wrote. “We debated whether this substance, which flows melted from underneath the earth, could occasion so many earthquakes.”

Long before the Spanish arrived, however, the site’s unique bubbling asphalt pits were known to the native inhabitants of the region. Prehistoric artifacts from the Chumash and Gabrielino tribes show the asphalt was used to waterproof baskets and canoes, mend pottery and add decorative shells to ceremonial items.

After El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles was settled in 1781, the citizens used the asphalt for fuel and as waterproofing for their roofs. The asphalt was such a significant local resource that a Mexican land grant transferring ownership of the ranch to the Rocha family in 1828 stipulated that citizens of the pueblo would retain the right to take as much “brea” from the site as they needed for their personal use.

In 1860, after California became a state, the ranchers were required to prove their land claims, a process that bankrupted many of them — including the Rochas, who deeded the site to Henry Hancock, the lawyer who had represented them in their claim. Hancock was also a businessman interested in developing the site for commercial extraction of oil and asphalt, which he sold for about $15 per ton and shipped as far as San Francisco, Calif.

Over the years, bones were sometimes unearthed from the seeps, but they were thought to belong to modern wild or domestic animals seeking water that then became mired in the tar. The paleontological significance of the site was not understood until the 1870s when Hancock brought a large canine tooth that clearly did not belong to any local animal to William Denton, a geology professor at Wellesley College in Massachusetts, who recognized it as a fossil. The first scientific paper about the La Brea fossils was published by the Boston Society of Natural History in 1875.

©Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/Page Museum.

In the first decade of the 20th century, several investigations and excavations were conducted by some noted geologists, including W.W. Orcutt, a petroleum geologist with Unocal, F.M. Anderson, curator of the paleontology department of the California Academy of Sciences, and J.C. Merriam of the University of California at Berkeley.

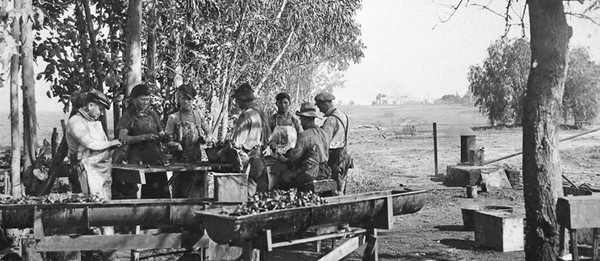

In 1907, J.Z. Gilbert, a biology teacher at Los Angeles High School, realized La Brea provided opportunities for both hands-on science learning and public outreach and began working with the Academy to bring scores of high school students to the site to learn how to excavate and clean fossils. The students found hundreds of fossils that were later displayed at the new Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

In 1913, Hancock’s son, G. Allan Hancock, granted exclusive rights to the County of Los Angeles to excavate the site for two years. More than a million fossils were found embedded in asphalt-impregnated sediment and gravel deposits in 96 different pits. Each fossil had to be painstakingly extracted using tiny picks and cleaned with hot kerosene.

The specimens recovered between 1913 and 1915 now make up the bulk of the collection of the Page Museum at the La Brea Asphalt Pits, which opened in 1977 in Hancock Park, the 9.3-hectare site that the Hancock family donated to the county in 1924.

Subsequently, much of the scientific work on the site was done by Caltech paleontologist Chester Stock, who had been a student of Merriam’s at Berkeley. Stock published the first comprehensive description of the La Brea site and fossils in 1930 and worked on the site until his death in 1950.

The treasure trove of fossils found at La Brea allowed Stock and others to recreate a remarkably complete picture of the ecosystems that existed in the region between 40,000 and 4,000 years ago. Forty percent of the mammal species found in the pits are now extinct, as well as 15 percent of bird species. Although herbivores usually outnumber carnivores in ecosystems, 70 percent of the animals found at La Brea were birds of prey or carnivorous mammals, the most abundant of which were dire wolves, with more than 4,000 recovered. Many of the La Brea species, however, including all of the smaller carnivores, are still alive today, including coyotes, foxes, domestic dogs, badgers, skunks and weasels.

Kathleen Cantner, AGI.

Scientists think the over-representation of carnivores occurs because prey animals mired in the asphalt attracted predators, which then became trapped as well, attracting even more predators. The sticky bitumen also ensnared a wide range of other fauna and flora, including fish, frogs, turtles, snakes, insects, plants, wood, pollen and diatoms, which resulted in the unique preservation of entire food chains in one locale.

Because of the unique abundance of individual fossils and the number of species represented, in 1951, the site was named the type locality for the Late Pleistocene Rancholabrean Land Mammal Age in North America.

In 1963, Rancho La Brea was designated a National Natural Landmark by the National Park Service.

Beginning in 1969, researchers who were concerned that earlier work focused disproportionately on the large extinct mammals reopened Pit 91, which had last been excavated in 1915, to sample the full range of fossils at the site.

The excavation of Pit 91 continued for 38 years and produced several new finds, including one that revealed that not all organisms in the tar pits are dead. In 2007, University of California at Riverside researchers discovered several previously unknown species of extremophilic bacteria living in the oil and asphalt.

More than a century after the first excavations and nearly 250 years after the pits were first described, the discoveries continue.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.