by Lucas Joel Tuesday, July 26, 2016

Yosemite Valley with Half Dome in the background. Although Yellowstone was the first national park, the idea of national parks can be traced to the federal government's 1864 decision to grant care of Yosemite to the state of California. Credit: AngMoKio, CC BY-SA 2.5.

The U.S. national parks are sanctuaries where one can find refuge in nature and marvel at its grandeur — from the glacially sculpted granitic monoliths of California’s Yosemite to the watery wilderness of Florida’s Everglades. This August, the agency that works to ensure the parks’ preservation for future generations, the National Park Service (NPS), celebrates its 100th anniversary.

When the notion of creating national parks emerged in the 19th century, it was new in the world: Setting aside portions of the natural landscape for what was called “the benefit and enjoyment of the people” had never been done before.

Today, the U.S. has 59 national parks and more than 350 other sites under the auspices of the NPS. Many were established only after hard-won fights to wrest control of and preserve natural sites from competing commercial interests. Early in the service’s history, the struggles to protect the parks were pitted against the ideals of Manifest Destiny — a 19th-century doctrine proclaiming U.S. expansion and settlement across the continent as both justified and inexorable. Now, Yosemite spokesman Scott Gediman explains, the NPS faces a slightly different struggle: maintaining the parks’ relevance, especially among younger generations.

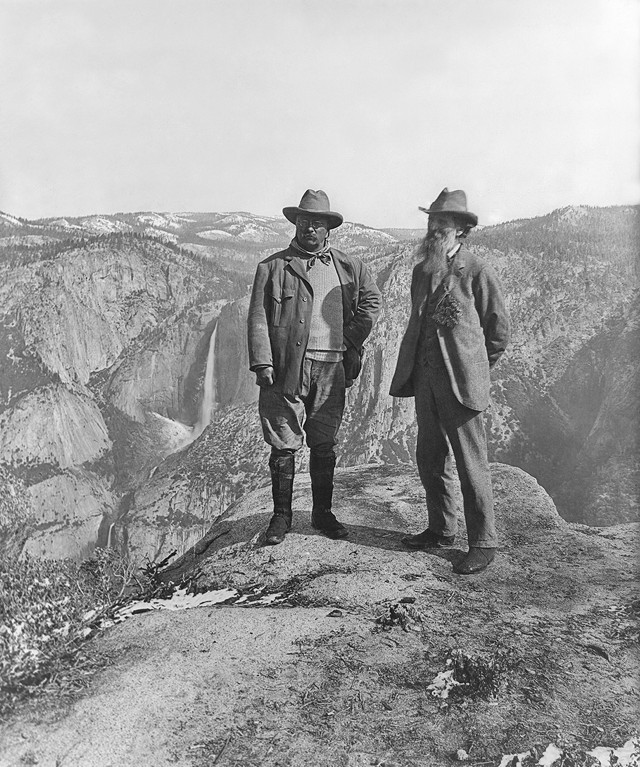

John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt during a Yosemite camping trip in 1903. During this trip, Muir spoke with Roosevelt about the need to give national park status to Yosemite Valley. Credit: Library of Congress.

At the time, the U.S. was still attempting to distinguish itself from “Old World” Europe, as Dayton Duncan and Ken Burns wrote in the companion book to the PBS documentary “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea.” Although the U.S. lacked the cultural grandeur of Europe’s cathedrals, centuries-old cities and millennia-old ruins, the feeling emerged “that America’s greatness could best be measured in the natural wonders it seemed to possess in such abundance,” Duncan and Burns wrote. “Whatever it might lack in terms of an ancient Parthenon or a grand cathedral or a museum filled with cultural treasures … America more than compensated for in its endless forests, stunning canyons, and awe-inspiring waterfalls.”

But the country’s natural wonders were already under threat. By the 1860s, one landmark, Niagara Falls, which is today America’s oldest state park, had already been tainted by commercialization: Private landowners charged visitors a fee to access spots overlooking the falls. Today, towering hotels and casinos riddle the landscape around the falls, and, for entertainment, the falls are lit aglow at night with multicolored spotlights. “To Europeans, Niagara Falls was not evidence of America’s superiority in terms of nature’s gifts; it was proof that the United States was still a backward, uncivilized nation,” Dayton and Burns wrote. Conness’ proposal to protect Yosemite, then, was an opportunity to avoid a similar embarrassment.

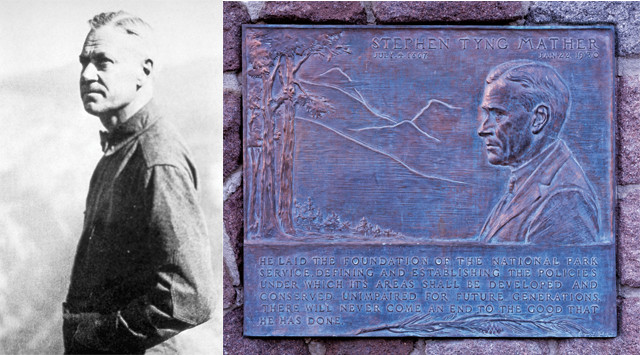

Stephen Mather (left), the first director of the National Park Service, is commemorated in every national park with a plaque like the one above at Lassen Volcanic National Park in California. Credit: left: Library of Congress; above: National Park Service.

“, described a similar experience upon first seeing the park: “It has been my lot to wander in many lands, and see the glorious places which men call wonderful; never have I looked upon a sight so majestic, so perfectly incomparable as the first view of Yosemite.”

Yosemite became protected in 1864, but private interests were still a problem: A pioneer named James Hutchings was running a hotel in the valley where he charged people to see the park, even though the land was now public. Hutchings, looking to improve his business, sought someone to harvest lumber and build and run a sawmill. The person he hired for that job — a wandering Scottish-born shepherd from Wisconsin named John Muir — would, after first seeing Yosemite, go on to become one of the most passionate and vocal supporters of protecting and preserving what he called “by far the grandest of all the special temples of Nature I was ever permitted to enter … the sanctum sanctorum of the Sierra.”

Tensions with Hutchings grew, prompting Muir to quit in 1871 and begin writing of his love for Yosemite Valley and the Sierra Nevada in publications like the Overland Monthly and, later, Century Magazine. His zealous words stirred readers, and, while he lamented that the time he spent writing could have been time spent hiking through his beloved Sierras, he once wrote in a letter to a friend: “I care to live only to entice people to look at Nature’s loveliness.”

Muir also had an academic background in geology, and he showed that Yosemite Valley and its surroundings had been sculpted by the erosive action of ancient glaciers. Although this idea is now widely accepted, at the time it ran contrary to the hypothesis of California’s then-state geologist Josiah D. Whitney, who theorized that Yosemite formed during an enormous collapse of the valley’s floor.

Years later, in 1889, after a long absence from the park, Muir revisited Yosemite with the editor of Century, Robert Underwood Johnson. But Yosemite was in trouble: Garbage littered the valley floor, and meadows were being used to grow hay and herd livestock. In the country above Yosemite, logging and sheep herding had erased the wildflower-laden landscape. For the destruction they wrought, Muir called the sheep “hoofed locusts.”

By the time of Muir and Johnson’s 1889 visit to Yosemite, the first national park, Yellowstone, had already been designated for 17 years. Although Yosemite Valley was still under control of the state, Johnson suggested to Muir that maybe the high country around the valley could become another national park. Muir agreed, and, through his writings and Johnson’s support, Congress was soon besieged by petitions to protect Yosemite’s high country. On Oct. 1, 1890, President Benjamin Harrison designated roughly 364,000 hectares surrounding Yosemite Valley as a new national park.

In later years, Muir’s ardor moved many others to protect the parks: In 1903, a Yosemite camping trip with President Theodore Roosevelt helped Muir eventually win the fight to incorporate Yosemite Valley into the national park that already surrounded it. In 1912, on a hike in the Sierras, Muir’s words inspired Stephen Mather, who would go on to become the first director of the NPS.

Mather, disturbed by the decrepit conditions he saw in parks like Yosemite, wrote a letter to Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane in which, according to Gediman, Mather said, “It’s great that you have these parks, but the animals are being killed and in Yosemite the rivers are being polluted by miners.” Lane responded that if Mather didn’t like the way the parks were being run, he should come to Washington and “run them yourself.” Mather did just that, and, through his lobbying efforts, the NPS was established on Aug. 25, 1916, when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Organic Act into law.

Mather helped define the NPS as we know it today by helping assemble, for instance, the first generation of park rangers, and by promoting public visitation to the parks by overseeing construction of extensive scenic park roads. After his death in 1930, bronze plaques commemorating Mather were laid down in every park. Each is identical, and each ends with the phrase: “There will never come an end to the good that he has done.”

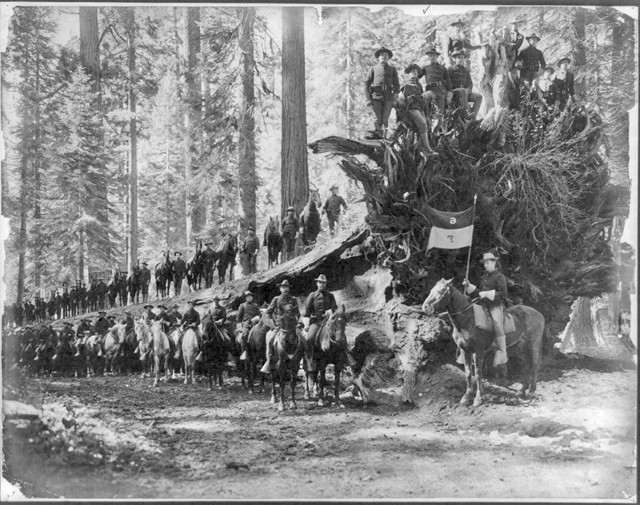

The "Fallen Monarch" — a giant sequoia in Mariposa Grove in Yosemite National Park — surrounded by Company F, 6th Cavalry of the U.S. Army. The army protected the national parks before the formation of the National Park Service in 1916. Credit: Library of Congress.

Today, the NPS oversees 411 park units, including the 59 national parks, as well as national monuments, lakeshores, rivers and historical parks.

Although the NPS is perhaps most associated with majestic natural places like Yosemite, the service also helps curate America’s historical identity at places like John Muir’s house and the Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front Historical Park, both in California.

Tucked in a harbor across the bay from San Francisco in Richmond, Calif., the Rosie the Riveter park, opened in 2000, commemorates the contributions women made in the American workforce during World War II. The new visitor education center exhibits artwork and artifacts from when women worked in the former shipyard complex at the site. “The exhibits here help us reflect on how war affected life wherever people were,” says Raphael Allen, a park guide. “So it’s a park about big changes at home, and it raises questions about how much of what happened in the ‘40s is still with us.”

Today, the national parks continue to face challenges. Sue Fritzke, an NPS deputy superintendent in California’s Bay Area, says that “one of the huge issues that we have is related to the fact that, within the next few years, approximately 80 percent of the American population will live in urban areas, and that 80 percent may not be wanting to spend a lot of time in big wilderness parks like Yosemite and Yellowstone.”

To address this, the NPS started the Every Kid in a Park program, which grants free national park access to every fourth grader in the country and their families. (Fourth grade is the year most schools teach state history.)

Fritzke says she thinks future generations looking back on the NPS of today will notice a shift “in terms of our recognition of reaching out to the population, and focusing a little less on … the big parks, and [more] on local integrated programs within urban areas.”

Another big challenge facing the NPS, of course, is funding. Since its inception, the park service has relied on multiple funding sources: allocations from Congress, park service fees, and public and private philanthropic donations, among others. Last February, the park service launched its Centennial Campaign for America’s National Parks, a campaign to raise $350 million to support the parks. In March, the director of the NPS released a proposed update to the philanthropy policy allowing corporations to be recognized for their donations, such as allowing company logos on some signs and printed materials, as well as park vehicles, buildings or exhibits. The new policy would also allow park officials to become more active in fundraising attempts. Despite some uproar and jokes about corporate sponsorship of parks and features, the policy is set to go into effect by the end of the year.

For now, the NPS is doing its best to ensure that if you visit any of the sites it manages — be it wild like Yosemite or urban like Rosie the Riveter historical park — you will find park service personnel ready to tell you that place’s story. And if you are lucky, you may come across someone as enthusiastic about America’s natural scenery and history as Muir, Mather, Fritzke or Allen, who may just inspire an even greater appreciation of these areas in you.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.