by David B. Williams Tuesday, August 23, 2016

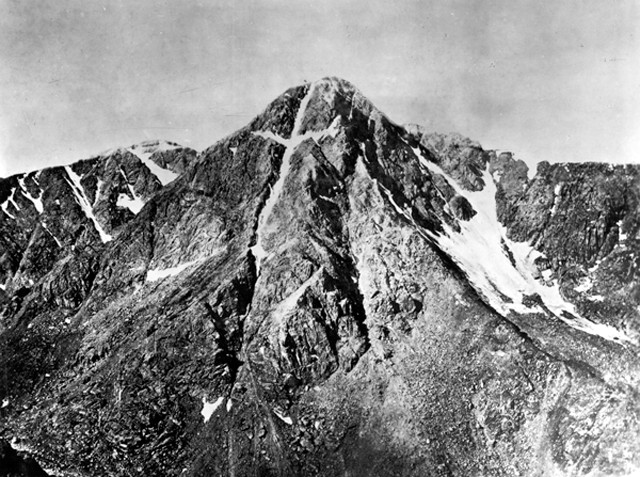

The Mount of the Holy Cross in Colorado, as photographed by William Henry Jackson in 1873. Credit: USGS Photographic Library.

The rumors had persisted for decades, some said for centuries. Deep in the Colorado Rockies was a mystical mountain. Upon the face of a towering peak rose a massive cross, formed by snow accumulating in two huge cracks. In his 1868 book, “The Parks and Mountains of Colorado: A Summer Vacation in the Switzerland of America,” journalist Samuel Bowles wrote, “It is as if God has set His sign, His seal, His promise there — a beacon upon the very center and hight [sic] of the continent to all its people and all its generations.”

No one knew the cross’s true size. Most estimates put the vertical span at more than 600 meters long, with the horizontal arms stretching 230 meters across. Nor did anyone know its true location. Yale botany professor William H. Brewer, who described the peak a year after Bowles saw it, called it the Mount of the Holy Cross. He claimed he could see it — a “cross of pure white, a mile high” — from the top of Grays Peak, a 4,350-meter-high summit 70 kilometers west of Denver. But that was the most accurate account of its location, until 1873.

In the summer of 1873, geologist Ferdinand Hayden’s monumental undertaking, the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories — a multiyear study focusing primarily on Colorado and Wyoming, including Yellowstone National Park — was under way. The members of the survey decided that they needed to pinpoint the location of the majestic, mythical snow cross. On maps, the mountain was as much as 50 kilometers “out of place,” Hayden told a congressional committee the following year.

William Henry Jackson, an explorer, painter and photographer, led the summer’s explorations in Colorado, along with surveyor James Gardner and illustrator William Henry Holmes. Jackson had been Hayden’s photographer in Yellowstone, and his photographs had helped convince Congress to make it the world’s first national park in 1872.

Mount of the Holy Cross in the clouds, as depicted by the Detroit Photographic Company in 1900, 27 years after the mountain was officially "found" and mapped. Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Through the summer of 1873, Jackson asked miners, prospectors, journalists, anyone he could, if they had seen the cross. No one had personally, but many knew of someone who had. “Wasn’t this man’s grandfather, and that man’s uncle, and old so-and-so’s brother the first white man ever to lay eyes on the Holy Cross — many, many, many years ago?” wrote Jackson in his 1940 autobiography “Time Exposure.”

Late in August, with their survey season about to end, Jackson’s men finally learned that the great cross lay west of Tennessee Pass, about 12 kilometers north of Leadville. They arrived at the pass on Aug. 19, still separated from the peak by more than 30 kilometers. For three days, they pushed on, past unstable rock slides, traversing narrow ledges cut into steep walls high above the valley on trails so treacherous they had to walk their animals. They camped a night in a swamp and could see no sign of the cross from the incised canyons. Holmes later wrote in the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly in 1927 that the mountain faces “bristled like a porcupine” and that the group encountered “countless multitudes of giant pinetrunks, uprooted by some fierce hurricane … piled up and crisscrossed and tangled in such a way that an army must have been stopped as before the walls of an impregnable fortress.”

The path appeared to open up on Aug. 22, with what looked like a promising peak rising out of the valley. But the searchers found their way blocked again. The next day the men split into two groups. One group, which included Gardner and Holmes, and Hayden, who had joined for the final search, would attempt to reach the summit. Jackson and his team, each of whom was carrying more than 18 kilograms of glass plates, cameras, chemicals, and photographer’s tents, planned to take photographs from across the valley.

Hiking in the rain with their own heavy surveying supplies, Hayden’s crew forged up the mountain but failed to make the ascent because of the weather. They spent the night in the cold with neither food nor bedding. Their only comforts were a campfire and an occasional exchange of shouts with Jackson’s crew, also holed up on a ridge across the intervening valley.

The party that made the first ascent of the Mount of the Holy Cross in 1873: Explorers and surveyors Ferdinand Hayden, James H. Stevenson, William S. Holman, S.C. Jones, James Gardner, W.D. Whitney and William Henry Holmes. The ascent was challenging, forcing the men to camp out several nights without shelter. The photo was taken by William Henry Jackson. Credit: USGS Photographic Library.

On Aug. 24, both teams reached their respective goals. Hayden and his men became the first to ascend the Mount of the Holy Cross, and to determine its location and elevation of 4,319 meters. (A 1964 survey put the peak at 4,268 meters.) Across the valley, Jackson at long last could see the mystical landform. “Near the top of the ridge I emerged above timber line and the clouds, and suddenly, as I clambered over a vast mass of rocks, I discovered the great shining cross dead before me … It was worth all the labor of the past three months,” he wrote in his autobiography.

With the weather still too dreary for photographs, Jackson and his companions spent another night out in the elements. Fortunately, the next day broke clear and they collected a handful of shots, which would help make the mountain world famous. In the following years, Jackson returned at least four times, but never got as good a shot as he did that first day.

Roches moutonnées near the foot of the Mount of the Holy Cross, looking up the valley, as photographed by William Henry Jackson in 1873. Credit: USGS Photographic Library.

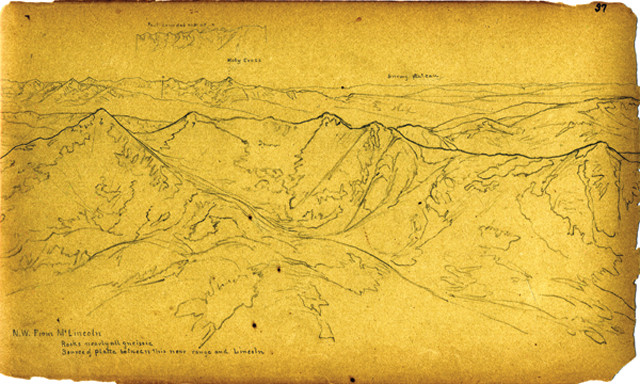

This lithograph was made in 1873 during the Hayden/ U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. The view is to the northwest from Mt. Lincoln, with the Mount of the Holy Cross on the horizon. Credit: USGS Photographic Library.

Like many peaks in Colorado, Mount of the Holy Cross is a mass of Precambrian rock. Specifically, it is a metamorphic suite of gneiss and migmatite that rises at the north end of the Sawatch Range. The Sawatch contains Colorado’s four highest peaks and three of the five tallest mountains in the lower 48 states.

No specific geologic event accounts for the cross, says Joe Allen, a geologist at Concord University in West Virginia. He traces the initial development to 1.7 billion years ago when the Cross Creek batholith intruded just north of the mountain and baked the surrounding country rock. This formed the migmatite and generated a metamorphic foliation, a planar feature that now trends nearly vertical. “The upright of the cross is likely tied to preferential erosion along this foliation,” Allen says.

This 1.7-billion-year-old intrusion also developed a northeast trending zone of weakness — visible on the area’s geologic map — that could have influenced recent glacial erosion and exposed the steep northeastern face that bears the cross to this day. Other influences include the uplift of the Rockies during the Laramide Orogeny — which pushed the crystalline basement rocks to their present elevation — and the development of the Rio Grande Rift Valley between 35 million and 25 million years ago, which Colin Shaw, a geologist at Montana State University, calls the “unzipping” of the continent. “The joints of the cross are a composite of all of these scarring events,” Shaw says. However, both Shaw and Allen note that these are speculative ideas and that they cannot say for sure what forces are at play in the creation of such a relatively small feature.

Geologic processes still affect the Holy Cross; it no longer looks the same as it did when Jackson photographed the mountain. No one knows when exactly, but by the 1930s or ‘40s, erosion had altered the cross’s right arm.

Such erosion could account for the mountain’s changing political fortunes as well. Two years after Jackson’s photograph put Holy Cross into the spotlight, its status soared when artist Thomas Moran painted a sublime scene of the great cross. By the 1910s, the mountain had become a pilgrimage site, with hundreds of people climbing Notch Peak where Jackson took his photos. So many pilgrims arrived early in the 20th century that on May 11, 1929, President Herbert Hoover established the Holy Cross National Monument, protecting 560 hectares around Notch Peak and Holy Cross.

Soon thereafter, thousands of people made the trip to climb Notch Peak in hopes of salvation. Those who couldn’t climb sent handkerchiefs, which others, including U.S. Forest Service employees, would carry up the notch.

By 1938, however, large-scale pilgrimages had ended, wrote Kevin Blake, a cultural geographer at Kansas State University, in the Journal of Cultural Geography in 2008. One major factor was the U.S. Army establishing a mountain and warfare training camp that abutted the national monument and made access more difficult. Some have proposed that the military bombing may have led to a rock slide that damaged the right arm of the cross.

Blake also suggests that part of the reason people stopped visiting is due to the “thousands of re-touched lithographs, woodcuts, postcards, paintings and photographs [that] ensured that no matter what image a visitor had in mind of the cross, it was unlikely to be faithfully duplicated on site.” The mountain’s popularity declined so much by mid-century that on Aug. 3, 1950, Congress abolished the national monument. However, people have not forgotten the Holy Cross and, in 1980, it became the centerpiece of the Holy Cross Wilderness, which covers almost 50,000 hectares.

People still make pilgrimages to Notch Peak and still climb the Mount of the Holy Cross, where, if the conditions are right, in early summer, they can still make out a rough cross of snow, though it has been diminished since Jackson first saw it in 1873. (By late summer, the snow in the couloirs, or vertical cleft, is usually melted out.) As Blake wrote, “more than a symbol of diminished religious significance, the changing appearance of the snow-filled couloir is a testament to dynamic geographical imaginations and natural processes, and to the uncertainty that occasionally pervades our understanding of each.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.