by David B. Williams Friday, November 20, 2015

Teapot Dome in Wyoming today and in 1927 (inset). Credit: both: courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy.

On Aug. 2, 1922, U.S. marines took over the oilfields at Teapot Dome. Credit: courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy.

Early in the morning of Aug. 2, 1922, soldiers from the United States Marine Corps arrived at the train station in Casper, Wyo. They had been traveling for three days from the East Coast to reach an important government facility, officially designated the Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3 (NPR-3), better known as Teapot Dome. Their orders, which President Warren Harding had approved only the week before, were to evict trespassers from a small oil claim in the northern end of the reserve. Following a quick breakfast, the soldiers proceeded north by car under the command of Capt. George K. Shuler. He had hand-picked the men, with whom he had fought in World War I.

In later testimony at a congressional hearing, Shuler stated that his team reached their destination around 10:00 a.m. and found barbed wire recently strung around the claim. He asked to see the boss, Harry O’Donnell, and ordered him to stop working. O’Donnell refused. Shuler replied that he had come under the authority of the Secretary of the Navy and that he was “absolutely serious” about evicting O’Donnell’s crew. Backing up Shuler’s words, his men wore “pistols and rifles and belts full of ammunition, and everything that goes with it,” as was noted in his congressional testimony. By noon, the drilling stopped and the Marines took the property and confiscated tools and other equipment. They ate lunch with the trespassers, and Shuler’s men set up camp to spend the night. The next day they posted “No Trespassing” signs. By Aug. 5, Shuler and the four soldiers were on a train back to Washington, D.C.

The Marine invasion of Teapot Dome was one of the many shenanigans and illegal activities orchestrated by President Harding’s Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall. Fall had pushed Harding to order the invasion because he had already leased the area to corrupt oilmen. The squatters were in the way. Congressional investigations later determined that Fall had received more than $400,000 for facilitating the illicit leasing. Seven years after the invasion, Fall became the first cabinet officer of the United States to be found guilty of a felony while in office. Ever since, the Teapot Dome Scandal has been synonymous with presidential corruption and abuse of power.

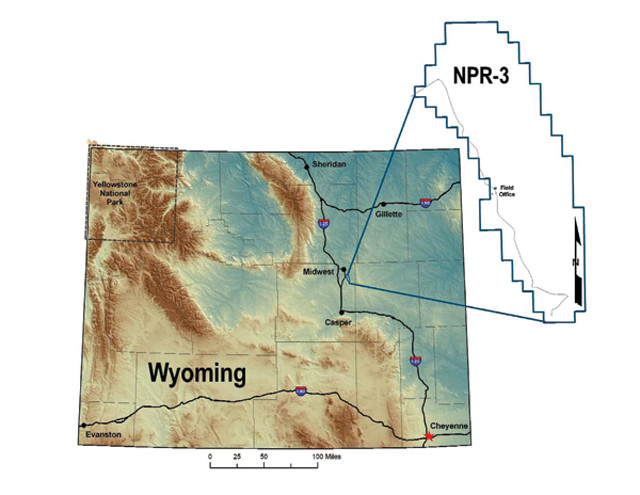

Map of the Teapot Dome oilfield, otherwise known as Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3 (NPR-3). Credit: courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy.

Oil gushes from wells at Teapot Dome in the early 1920s. Credit: courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy.

As part of the U.S. Navy’s conversion from a coal-powered to an oilpowered fleet, courtesy of the Pickett Act of 1910, President William Howard Taft was authorized to designate three petroleum reserves for the Navy to tap into in case of an emergency, such as a war: He chose Teapot Dome in Wyoming and two sites in California, Elk Hills (NPR-1) and Buena Vista (NPR-2).

Private interests had long coveted these reserves. As early as 1880, oil had been reported in the Salt Creek oilfields adjacent to Teapot Dome. Production didn’t ramp up until 1910, and by 1918, Salt Creek was producing 10,000 barrels of oil daily, with the U.S. Geological Survey estimating the oilfields contained more than 100 million barrels in total. Some 30 million more barrels of oil were estimated to lie in the Teapot Dome field, in Upper Cretaceous and Pennsylvanian sandstone beds, at depths ranging from 122 meters to 1,676 meters.

Primary among those who pursued a lease to drill was Edward Doheny, owner of the Pan American Petroleum Company and one of the most powerful oilmen in the world. George Creel, who headed the U.S. propaganda effort during World War I, described Doheny as “a man who seemed utterly unable to view anything except in the light of his own desires.” Despite entreaties by Doheny and his operators, the Navy had continually resisted pleas to open their reserves in California and Wyoming to private interests.

To persuade officials of the value of private drilling, the oilmen argued that Teapot had to be drilled or else the oil would be lost to outside interests. They argued that because the oil reservoirs were in permeable sandstone, drilling near the reserve would draw oil out of the reserve, and deprive the government of a valuable commodity. According to a 1924 New York Times article, Fall’s assistant, Edward Finney, said that without this drilling, “within a few years the government reserves would be depleted.”

Below: Some oilmen argued in the early 1920s that oil producers working in the Salt Creek oilfields (top) — adjacent to the Teapot Dome oilfields (bottom) — would siphon oil out of the Teapot Dome reservoir. Credit: both: U.S. Geological Survey photographic library.

Albert Fall was a senator from New Mexico for nine years before being named Secretary of the Department of the Interior. Credit: Library of Congress.

Harding, who campaigned on a promise to return the country to “normalcy” after the disorder of World War I, won the 1920 presidential campaign in a landslide. On the day of his inauguration in March 1921, he submitted a list of his cabinet nominations, starting with Albert Fall, to the U.S. Senate. Within 10 minutes, they were all approved.

Harding knew Fall from their days together in the U.S. Senate, and their many evenings of drinking and pokerplaying. While Harding was a womanizer (he had at least two well-known affairs, one while in the White House), Fall, who had been a senator from New Mexico for nine years, had a reputation as a gruff, independent fighter. One of Fall’s first acts in 1921 was to convince Harding to transfer authority over the three petroleum reserves from the U.S. Navy to the Department of the Interior, giving Fall full control over leasing decision for the sites.

Nine days after Fall had gained control of the leases, he wrote to his old friend Doheny; with regard to oil leasing, he stated, “I shall handle matters exactly as I think best and will not consult with any officials of any bureau.” Initially interested in the Teapot reserve, Doheny now turned his attention to the reserves in California, located 160 kilometers north of Los Angeles’ oilfields. In July 1921, Fall awarded Doheny a small lease in the Elk Hills reserve. Not satisfied, Doheny complained to Fall that he wanted access to the entire reserve, estimated to contain 300 million barrels of oil. In return, he would build oil storage tanks for the Navy at Pearl Harbor.

Doheny also promised to “lend” Fall money to purchase property adjacent to his 30,300-hectare Three Rivers Ranch in New Mexico. On Nov. 21, 1921, Doheny’s son, Ned, arrived at Fall’s Washington, D.C., apartment carrying a little black bag containing $100,000 in cash. Fall acknowledged the “loan” with a handwritten IOU, although Doheny did not keep any record of the transaction.

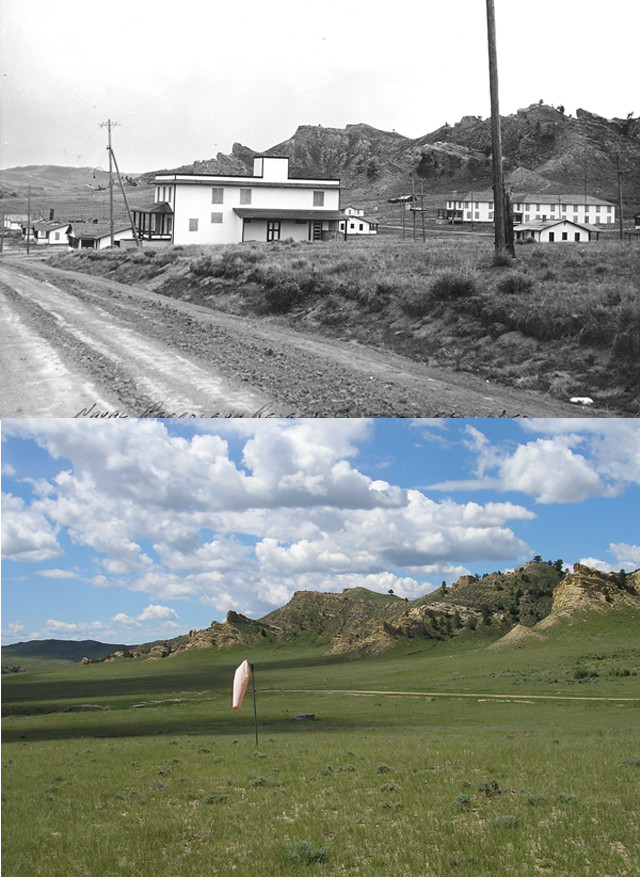

Oil was produced from Teapot Dome from the early 1920s until 1927. The Navy sold off most of the buildings and parts from the production starting in 1928. Credit: courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy.

Five weeks later, Fall, now at his ranch, had another set of visitors. This group was led by oilman Harry Sinclair. Sinclair stated that he was there to discuss his oil leases on the Osage Indian Reservation primarily in Oklahoma, but on his final day, he also raised the prospect of leasing the Teapot Dome fields. In a subsequent report to Harding, Fall wrote that he told Sinclair that he would consider the idea and would be open to a proposition. On Feb. 3, 1922, Sinclair presented his proposal to Fall — along with a racehorse and livestock, in “appreciation of Fall’s hospitality.”

That month, Fall received a new geologic report on Teapot Dome. Arthur Ambrose, chief petroleum technologist for the U.S. Bureau of Mines, now put the reserve estimate at more than 135 million barrels of oil under Teapot Dome, with an additional 360 million barrels under the nearby Salt Creek field. If Teapot contained that much oil, Sinclair stood to make more than $100 million, as typical profits were about a dollar a barrel. Ambrose also reported that there was no immediate concern of oil being drawn out of the reserve due to nearby oil operations, but Fall ignored this item.

On April 7, 1922, Fall signed the lease for Teapot Dome over to Sinclair without accepting any other bids. Fall did not go public with his decision. He later claimed that he didn’t divulge the information because he did not want to reveal “military secrets.” Fall also didn’t tell anyone that Sinclair had delivered $233,000 in government bonds to Fall, supposedly because his ranch had so enchanted Sinclair that the oilman had decided to purchase part of it.

Teapot Dome turned out not to contain the huge oil reserves once thought. Cumulative production at Teapot Dome now stands at about 30 million barrels, most of it pumped since 1976; only about 3.55 million barrels were produced in the 1920s. Below: NPR-3 main camp in 1942 and today. Credit: bottom: Tom Anderson, U.S. Department of Energy; top: courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy.

Sinclair’s men started to drill in July 1922 — only slightly inconvenienced by the squatters who were swiftly removed by Harding’s order and the action of the Marines in August — and in October they completed the first well. By the end of 1923, the men had put in 83 wells, 60 of which produced oil. They reached a peak monthly production of 138,082 barrels of oil by October 1923 — the same month that formal hearings on Fall’s chicanery at Teapot Dome began in the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys. By this time, Fall had resigned — he left office on March 4, 1923, to devote time to private business — and President Harding had died of a stroke on Aug. 2, 1923.

Sen. Thomas Walsh of Montana presided over the hearings, which few expected to produce titillating results. Fall, Doheny and Sinclair initially denied any wrongdoing. But after months of testimony and probing, Doheny finally admitted in January 1924 that he had lent Fall $100,000, for no other reason than that they had been friends for 30 years. It certainly had nothing to do with the $100 million he expected to make from his leases of the reserves in California. Congressional testimony ended in May 1924. Then, the nation’s courts began to consider these events. Over the next six years, trials on various aspects of the scandal took place across the country. The Supreme Court ultimately voided Sinclair’s and Doheny’s leases as a result of Fall’s shady maneuvers. Meanwhile, Sinclair was found in contempt of the Senate and sentenced to three months in jail. He was also found in contempt at a later trial for jury tampering and received another six months in jail.

Fall and Sinclair were more successful in yet another trial, in which they were found not guilty of conspiracy to defraud the government, despite a previous revelation that Sinclair had “loaned” Fall an additional $71,000 in cash. Finally, on Oct. 25, 1929, a jury found Fall guilty of accepting a bribe from Doheny. Fined $100,000 and given a one-year sentence, Fall served his time in a New Mexico prison.

Teapot Dome turned out not to contain the huge oil reserves that the Bureau of Mines’ Ambrose thought it would have. On Dec. 31, 1927, when the federal government shut down all operations at the naval reserve, total production only amounted to 3.55 million barrels of oil. An American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin published in 1977 estimated that Sinclair’s corporation spent close to $25 million on wells, pipelines and tank farms, putting the cost per barrel at about $7. At the time, oil sold for $1.30 per barrel.

As a result of the Supreme Court decisions, the Navy regained control of Teapot Dome, as well as the other two sites. The Navy sold off most of the facilities in 1928, salvaged what was left of the steel and pipes during World War II, and auctioned off the rest, including buildings, in 1949. In 1977, the Navy transferred the 4,050-hectare Teapot reserve to the Department of Energy. Cumulative production at Teapot Dome now stands at about 30 million barrels, most of it pumped since 1976, when the Arab oil embargo led President Gerald Ford to open up the Naval Petroleum Reserves for production. In contrast, the Salt Creek fields have produced more than 685 million barrels.

Teapot Dome got a new lease in 1993, when a joint effort by the Department of Energy, industry and academia established the Rocky Mountain Oilfield Testing Center (RMOTC). The center provides facilities for the oil and gas industry to field test new technology that will increase recovery and lower operating costs. RMOTC has produced oil there — now down to about 200 barrels per day — but the focus now is more on developing renewable energy sources. It is perhaps ironic that an area notorious for corruption has evolved into a showcase for what can happen when different interests work together for good.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.