by David B. Williams Wednesday, July 6, 2016

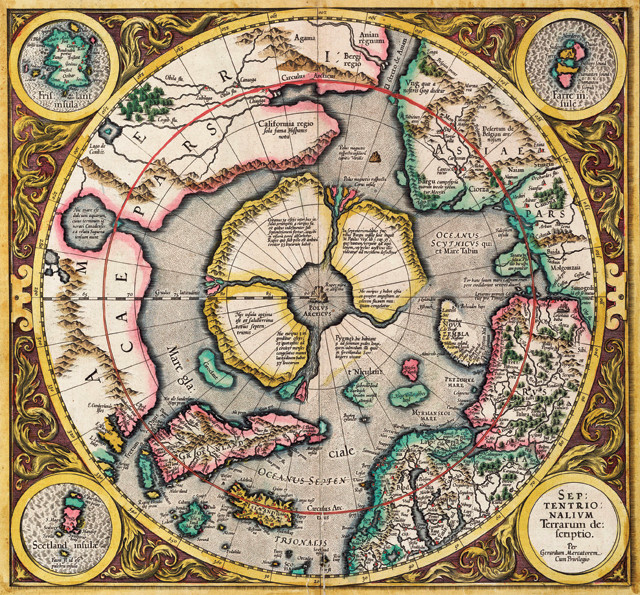

This plate was published in 1595 in Mercator's Atlas. It records attempts by Frobisher, among others, to find a northwest passage, and shows the pole surrounded by islands between which rivers flow. Credit: ©National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK.

Three small boats set sail westward from London on June 7, 1576. Their goal: Find a northwest passage across the Arctic to Cathay, or China. A former pirate, Martin Frobisher, captained the 34 men. By July 11 they had reached Greenland. A storm overtook them, sinking one boat and forcing another to return home.

Frobisher, aboard the third boat — the Gabriel — continued west with the remaining 19 men, “knowing that the sea at length must needes have an endyng, and that some lande shoulde have a beginning that way,” noted sailor George Best, who chronicled Frobisher’s three expeditions to the New World and sailed with him on two of them. Land appeared on Aug. 11, in the form of a rocky isle, south of Baffin Island. Five men landed and hiked to the high point, where mariner Robert Garrard picked up a coal-black rock the size of a “halfe pennye loafe.”

By late August, with a foot of snow already fallen, Frobisher headed back to England. He arrived in London on Oct. 6. Little did he know that Garrard’s stone would change history. According to Best, the stone ended up with the wife of a crewmember who “threw and burned [it] in the fire, so long, that at length being taken forth and quenched in a little vinegre, it glistered with a bright Marquesset of golde.” Taken to assayers in London, the stone was found to contain gold — “and that very ritchly for the quantity,” wrote Best.

Michael Lok, the expedition’s principal financier, told a different and less colorful story. According to Lok, when Frobisher arrived in London, he gave Lok the stone as a token of the success of the expedition. Lok broke his stone into smaller bits and distributed it to three “goldfyners,” or assayists, none of whom could find gold in their sample.

Not one to take no for an answer, Frobisher gave one final piece to London-based alchemist Giovanni Baptista Agnello in January 1577. Within days Agnello had obtained gold from the rock. When asked by Frobisher why he found gold when others could not, Agnello replied, “Bisogna sapere adulare la natura”: It is necessary to know how to coax nature.

Convinced of the prospect of gold, Lok decided to finance a second expedition across the Atlantic — to seek more riches in a land soon to be named Meta Incognita: the unknown limits.

Backed by Queen Elizabeth, who provided a naval vessel, the 200-ton Ayde, Frobisher set forth on May 25, 1577. More than 140 men, including eight trained miners, sailed with him in three ships: the Gabriel and the Michael, along with the Ayde. July 18 found them at Little Hall’s Island, where Garrard had picked up the stone the previous year. But this time, they found no trace of gold. On July 29, the ships landed on another dab of land, about 20 hectares in size, which Frobisher named Countess of Warwick Island in honor of one of their patrons. In addition to offering a safe, ice-free, level landing, the island (now called Kodlunarn, from the Inuit for white man) contained ore with “golde plainly to be seen.”

The eight miners set to work at the northern end of Kodlunarn, digging what is now known as “Ship’s Trench.” They produced 158.7 tons of black ore. With their bounty loaded onto the ships, the expedition returned home, where they placed the ore in storage protected by four locks; the four keys were distributed to four men.

Soon after their return in late September, the expedition’s assayer Jonas Schutz tested the ore and found it to contain 13.3 oz/ton of gold, or £40/ton, considerably less than the £240/ton that the expedition’s backers expected.

Despite the low-grade quality of the ore — the results were even worse in a subsequent assay — Lok and other investors planned a massive expedition for 1578. It wasn’t just that visions of gold clouded their judgment: The expedition financiers had relied on credit to pay for the first two voyages. If they couldn’t produce the gold, they could be ruined.

On May 31, 15 vessels carrying more than 400 men, including 150 miners, departed for Meta Incognita. Frobisher again led the expedition, which carried enough supplies for a colony that would overwinter on Kodlunarn Island. One hundred men would live in a prefabricated timber house 40 meters long by 12 meters wide.

Upon reaching the area around Baffin Island on June 27, the expedition found ice filling the straits. Dense fog and more ice slowed the ships’ advances and not until Aug. 1 could the boats find and land on Kodlunarn. Unfortunately, most of the prefabricated house materials were on a ship that sank. The expedition decided not to overwinter.

For the next month, the miners dug ore with pickaxes, sledges, crowbars and wedges. It could not have been pleasant work. Freezing temperatures were common. Cold winds blasted the men, who had little to protect them in the barren landscape. They quit one mine because the rock was “so uncerteinlie and crabbedlie [ill-temperedly] to gett.”

Kodlunarn housed the base of the mining operation, though it did not have the biggest mine. It produced 65 tons of ore, whereas the Countess of Sussex mine, nine kilometers to the west on Baffin Island, generated 455 tons. The men also mined an additional 621 tons from nearby sites, which modern researchers have not been able to pinpoint. With snow falling again, Frobisher and his crews returned to England, arriving in late October.

Schutz was again called upon to assay the black ore. He now worked at a huge complex in Dartford, about 30 kilometers down the Thames River from London. The ore was stored nearby in an empty chapel neighboring King Henry VIII’s Manor House, owned by his daughter Elizabeth.

No numbers survive from Schutz’s first three tests but the language speaks clearly: “verye evill,” “somewhat reasonable,” and “suceeded but evill.” Later tests conducted by others fared no better. By the end of 1578, everyone knew that the three years of expeditions, the expenditure of £20,000 (about £4 million in modern terms), and the loss of 24 lives had produced nothing of worth.

Principal expedition financier Michael Lok ultimately ended up in debtor’s prison eight times because of the Frobisher fiasco. Frobisher, in contrast, was eventually promoted to Vice-Admiral under Sir Francis Drake by Queen Elizabeth. Almost 300 years would pass before another British expedition landed on Kodlunarn Island.

In modern terms, the rock mined on Frobisher’s three expeditions was a 1.5-billion- to 1.8-billion-year-old biotite gneiss interfingered with black, hornblende-rich beds — the so-called “black ores” mined by Frobisher’s men. They are highly contorted rocks, and often produce isolated boudins, stretched-out lenses of rock embedded in a deformed matrix.

In the 1980s, mineralogist Donald Hogarth and geologist John Loop of the University of Ottawa in Canada reanalyzed samples of the black ore, mostly from Kodlunarn and Baffin islands, with a handful from Dartford in London. Half of these samples contained less gold than typically occurs in Earth’s crust. Hogarth and Loop concluded that the assayed samples had been contaminated — the lead used in assaying had also contained small amounts of gold.

But more recently, geologist Georges Beaudoin and archaeologist Reginald Auger, both of the Université Laval in Canada, tested lead from the assay sites on Kodlunarn Island. They found no detectable gold. Instead of accidental contamination, they concluded, the London assayers had salted their tests with gold.

Frobisher’s ore did not, however, go completely to waste — the residents of Dartford quickly found a use for it. In about 1579, more than 500 pieces of the black ore went into the western perimeter wall of King Henry VIII’s Manor House. They range in size up to 30 square centimeters — and may be some of the most expensive building stones in history.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.