by Erin Wayman Thursday, January 5, 2012

Today, re-enactments of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral lure tourists to Tombstone. by James G. Howes, 2008

Downtown Tombstone has been restored to its Old West Glory. Grombo, Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0

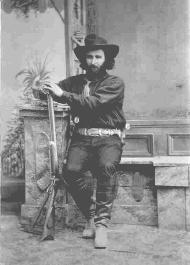

Prospector Ed Schieffelin in Tombstone in 1880. Arizona Historical Society

The Ed Schieffelin Monument, located near Schieffelin's original Tombstone claim. crbill, Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0

On April 1, 1877, Ed Schieffelin arrived at Fort Huachuca in southeastern Arizona. Schieffelin, a prospector who had tried his luck all across the West, came to the desert looking for untapped riches. The soldiers at the fort warned him that the only thing he’d find was his own tombstone. But by Aug. 1, Schieffelin found what he was looking for: silver. He named his first mining claim Tombstone.

Schieffelin’s discovery set off a silver rush in Arizona’s San Pedro Valley, and soon the entire area earned the name Tombstone. By 1881, the community grew to 4,000 residents, making it the largest city between New Orleans and San Francisco. That same year, Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday reached for their holsters during the infamous shootout at the O.K. Corral. Although that gunfight secured Tombstone’s legacy in American folklore, the region’s silver industry left a more tangible mark on history: Between 1879 and 1970, Tombstone produced more than $38 million worth of silver.

Arizona’s silver mining history began a few centuries earlier. Native Americans in the area mined a variety of substances, including cinnabar, turquoise and clay, as early as 1000 B.C. But it was not until the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 1500s that the search for more precious metals started. In 1736, a rich silver deposit, named Planchas de Plata (sheets of silver), was discovered on a ranch named Arizona in what is today Sonora, Mexico. Ranchers found slabs of silver, including one that weighed more than a ton.

The discovery of Planchas de Plata led to a small silver boom in the region, but silver mining in the modern-day state of Arizona didn’t really take off until the late 19th century. Federal laws made silver an attractive mining commodity. In 1873, silver had been demonetized. But the years-long economic depression known as the Panic of 1873 led some lawmakers to suggest re-establishing a dual gold/silver currency system, in part due to new discoveries of large silver deposits in the West. To that end, in 1878, Congress passed the Bland-Allison Act: Under the law, the U.S. Treasury had to buy $2 million to $4 million worth of silver each month to make currency, providing mining companies with a stable market. In 1890, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act replaced the Bland-Allison Act, requiring the federal government to buy 4.5 million ounces of silver every month.

Arizona in particular was an appealing place to mine silver because Arizona Territory Governor Richard McCormick had instituted laissez-faire policies in the 1860s to promote the territory’s mineral development; miners did not have to pay taxes on the products of their mines. With these favorable laws in place, prospectors began their hunt for silver in earnest in the 1870s.

One of these prospectors was Ed Schieffelin. Born in Pennsylvania in 1847, Schieffelin and his family soon moved west. He spent much of his childhood in Oregon, where he first tried his hand at prospecting. In 1864, he left home, and a series of odd jobs took him all across the West. In January 1877, he tried prospecting near Arizona’s Grand Canyon. After coming up dry, he traveled with a party of Indian scouts to Fort Huachuca. Near the fort was the nearly abandoned Brunckow Mine. Its owner did not operate the mine, but he hired workers to conduct an assessment each year so he could hold onto his claim. Schieffelin was hired as a guard. As he stood at his post, his prospector’s eyes noticed hills in the distance that looked promising. He decided to investigate the area.

“The [silver] ledges in Tombstone were pretty hard to find,” Schieffelin recalled in an interview years later. “They did not crop boldly out of the ground … All that summer I did not find anything of great importance; I found some good ores and good float [debris from an eroded lode deposit that gets washed away] and found several croppings … I found enough, however, to satisfy myself that there were good ores there, or ought to be.”

Despite the meager findings, Schieffelin traveled north to Tucson in August 1877 to file a claim, which he named Tombstone. He also filed a nearby claim, called Graveyard, on behalf of one of his fellow assessment workers. The first mining claims in the San Pedro Valley did not ignite a silver rush. Instead, Schieffelin’s continued search at Tombstone left him near penniless. With just 30 cents in his pocket and a few ore samples, he left Tombstone that fall to find his brother, Al, who was working at the Signal Mine in northern Arizona.

In January 1878, Al brought three of Ed’s ore samples to the Signal Mine’s assayer, Richard Gird. Gird was confident in his assessment skills. Before coming to the Signal Mine, he had made a topographical map of the Arizona Territory. Years later, Gird said in Out West magazine that his years of experience and geological knowledge meant he could “predict the kind of geological formation that produced the ore Al handed me.” Gird was pleased with what he saw: He assessed the most valuable ore, a sample from the Graveyard claim, to be worth $2,000 a ton.

Based on this ore sample, Gird suggested the three men leave the Signal Mine and head to Tombstone. The fact that Gird left a good job at the mine (and a promotion to superintendent) tipped off many local miners to the prospects in Tombstone. By the time the Schieffelin brothers and Gird reached Tombstone, they were not the only prospectors searching the area’s hills.

Despite the good ore samples, the Tombstone and Graveyard claims proved disappointing. But that didn’t deter Ed. He continued to comb the area for silver ore. One day, he brought Gird another sample, which Gird valued at $2,200 to the ton. “The next morning,” Gird recalled, “I went with Ed to the spot where he had picked up the piece of float … and soon found the Lucky Cuss ledge — the real discovery of the mines now known the world over as the Tombstone mines. I picked up more rich float, some of the pieces assaying as high as $9,000 a ton.” The partners followed up the Lucky Cuss find with the Tough Nut claim (like a tough nut to crack) and Contention (so named after a dispute with other miners over the claim).

The discoveries led to the silver boom that made Tombstone a bustling mining community. But the Schieffelin brothers didn’t stick around. In March 1880, they accepted an offer of $600,000 for their shares in the mining claims. Gird didn’t think the time was right to sell; he held onto his mining interests for another year, and then sold his rights for the same price.

Though the silver rush had barely gotten under way, the Schieffelins and Gird were probably smart to sell when they did. In 1893, Congress repealed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, and demand for silver plummeted — as did miners’ fortunes in Tombstone. Tombstone nearly became a ghost town until the town reinvented itself as a tourist destination, a place where visitors could experience the Old West and watch re-enactments of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. The site and surrounding county also became a popular movie set, with more than three dozen movies filmed in Cochise County, including “Tombstone” and “Young Guns II.”

Although Ed Schieffelin left Tombstone in 1880, he did not leave the town for good. In May 1897, he collapsed and died in the doorway of his cabin in Oregon, where he had moved to begin another round of prospecting. His body was brought back to Tombstone, and laid to rest with a pick and canteen near the original Tombstone claim.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.