by Timothy Oleson Monday, July 20, 2015

Expansive basalt lava beds cover much of the arid landscape, along with sagebrush and low vegetation, in Lava Beds National Monument. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/JeffGoulden.

By Timothy Oleson

Under the banner of manifest destiny and with the enticements of natural resources and vast unsettled lands, the western United States saw explosive population growth in the latter half of the 19th century. People flocked to California, especially, following the mid-century dawn of the gold rush. Between 1850 and 1870, the state’s population ballooned six-fold to roughly 560,000, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures. And with the increasing number of non-native settlers came increasing contact and, often, conflict with Native Americans.

The Modoc people, who had long subsisted on the volcanic landscape in the area of Tule Lake and Lost River in far Northern California and Southern Oregon, were among those progressively squeezed from their traditional homes. After about two decades of occasional violence (mostly involving California and Oregon militiamen), forced relocation efforts and on-again, off-again negotiations between the Modoc and the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs (later renamed the Bureau of Indian Affairs), an armed conflict began between the U.S. Army and factions of Modoc beginning in the fall of 1872.

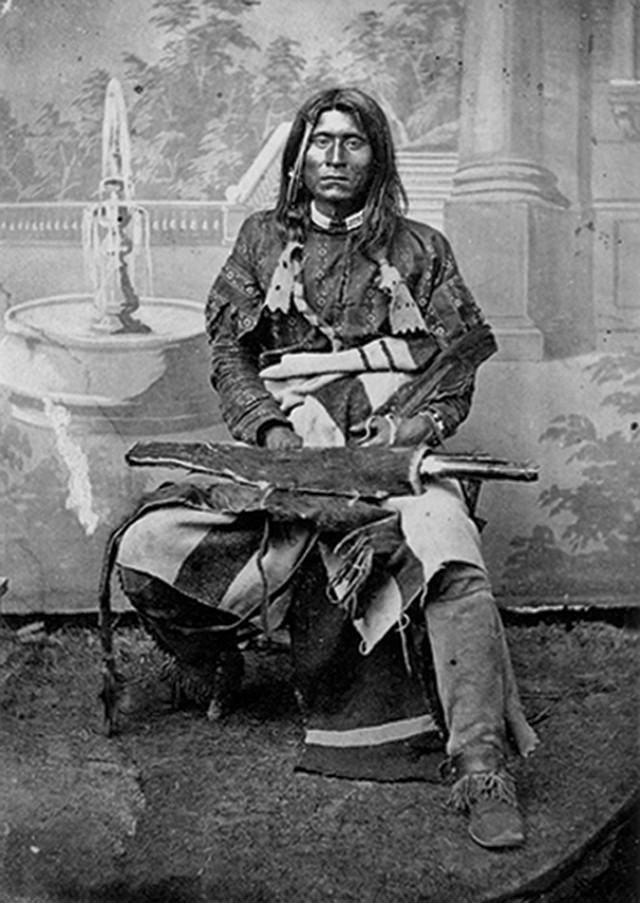

Over the course of six months, the sides fought a series of battles over rugged terrain — now part of Lava Beds National Monument — where the Native Americans used their familiarity with the land to great advantage. Vastly outnumbered, however, the Modoc force eventually succumbed when their leader, Kientpoos (or Kintpuash), surrendered on June 1, 1873. The so-called Modoc War, or Lava Beds War, proved costly for both sides, but especially for the Modoc, who were left fractured and displaced from their homeland permanently.

Corridors and crevasses through the labyrinthine landscape provided easy concealment for the Modoc during their battles with the U.S. Army in the lava beds. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/zrfphoto.

’' A couple of years after the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, nuggets of the precious metal were found about 360 kilometers farther north at Yreka, Calif., bringing an influx of prospectors and others to the northern part of the state. After years of skirmishes between settlers and Native Americans — occasionally involving misguided retaliations against innocent parties — the U.S. government first tried to resettle the Modoc on the newly established Klamath Reservation in southern Oregon in 1864. (Members of the Klamath and Yahooskin tribes, two other groups who inhabited the region, were simultaneously resettled on the same reservation.) The Modoc leader at the time, Old Schonchin, agreed to relocate from the tribe’s historic homelands near Tule Lake and Lost River, but not all of the Modoc were content with the move.

Between 1864 and 1870, bands of Modoc, usually led by Kientpoos — who came to be known as Captain Jack among U.S. forces and settlers — repeatedly left the reservation in Oregon to return to the shores of Lost River. Although they were compelled to return to the reservation several times, Kientpoos and his followers never stayed long. Not only did they resent being forced to move, but the Modoc also had difficulty living in such close proximity to their traditional rivals, the numerically superior Klamath. Further, the government failed to adequately furnish material support to the Modoc, as officials had agreed to do in the original resettlement deal.

' After months of failed negotiations and attempts to secure the Modoc their own portion of the Klamath Reservation, the Office of Indian Affairs and the Army decided that a show of force would be needed to convince Kientpoos’ group, who had set up a couple of camps along the Lost River, to relocate once and for all. On Nov. 29, 1872, a patrol of about 40 men from the 1st Cavalry regiment out of Fort Klamath rode to the camps, intent on arresting Kientpoos and two other Modoc men. A brief standoff between the sides was broken when an Army officer and one of the Modoc each drew their pistols and fired at each other, simultaneously, according to the accounts available. Neither shot connected, but the volley ignited firing from both sides in what would become the first encounter of the Modoc War.

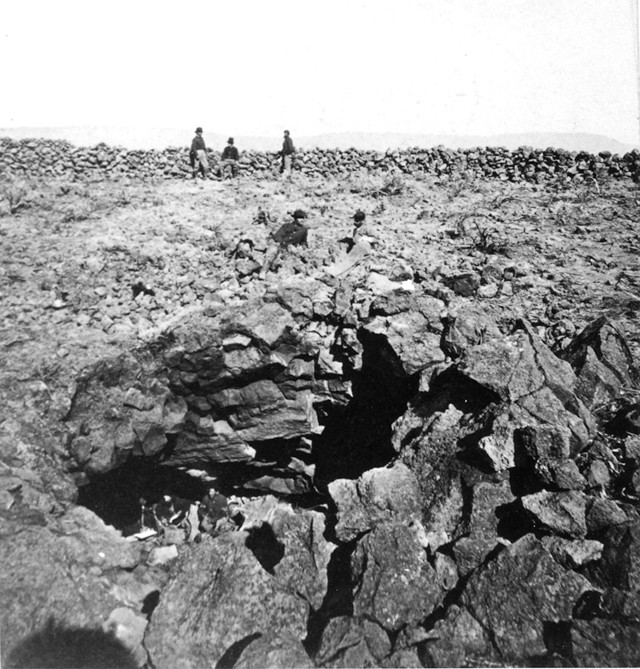

U.S. soldiers inspect Captain Jack's Stronghold in 1873. Credit: Eadweard Muybridge/U.S. National Records and Archives Administration.

Kientpoos, who came to be known by settlers and the military as Captain Jack. Credit: Southwest Museum; Eadweard Muybridge/U.S. National Records and Archives Administration.

In the wake of the initial battle, the Modoc retreated to the south side of Tule Lake, where they fortified their position as the government forces regrouped to plan their next action. Here, among sagebrush and other low shrubs, are heaps of jagged black basalt and scoria — the remnants of viscous lava flows from the massive Medicine Lake shield volcano, which has erupted occasionally over the last 500,000 years, driven by the same volcanism that created the Cascade Range farther north. Among the boulders, crevasses and gullies of the lava beds are also a multitude of caves, hollowed into ancient lava tubes. For the Modoc, who knew the area well, the labyrinthine landscape provided easy concealment. By contrast, it proved treacherous for government forces, who had little experience on such terrain and whose movements were easily tracked by the Native Americans.

In December, the Modoc launched attacks from their perch in the lava beds — dubbed Captain Jack’s Stronghold — inflicting casualties on militiamen positioned nearby. In response, the Army advanced on the Native Americans’ position beginning on Jan. 16, 1873. The government forces numbered about 300 and included U.S. Army regulars supported by volunteer militia from California and Oregon, as well as Howitzer cannons.

Beset by thick fog on the morning of their Jan. 17 assault, however, the troops were outmatched by the 50 to 60 Modoc fighters holed up among the rocks and caves along with their families. During the battle, the soldiers and militiamen purportedly never saw a single Modoc, who fired from concealed vantage points in their volcanic stronghold, killing or wounding about 35 men while sustaining no casualties themselves. The U.S. forces had no recourse but to retreat, leaving behind weapons, ammunition and several of the dead in their haste to escape.

Wood engraving of Modoc warriors in their stronghold among the lava beds, originally published in Harper's Weekly in May 1873. Credit: Library of Congress; top: public domain.

Following the disaster at Captain Jack’s Stronghold, the U.S. again pursued diplomatic efforts with the Modoc, while also amassing an even larger army at a new encampment just west of the lava beds. From February through mid-April, delegations from the U.S. Peace Commission, including many of the same people who had previously been involved with negotiations, met with Kientpoos several times. With the U.S. unwilling to create a new reservation for the Modoc along Lost River, and the Modoc loath to leave their homeland, the negotiations went nowhere.

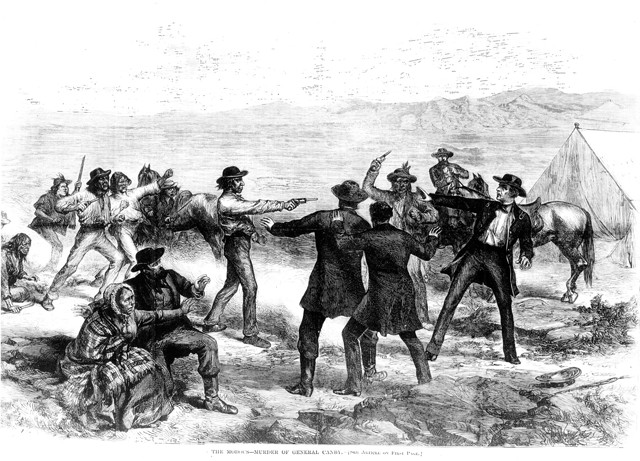

Despite indications that the Modoc were planning an ambush, the two sides met again on April 11 at a site midway between the stronghold and the Army’s camp. The peace commission included Edward Canby, the Commanding General of the Department of the Columbia — the military command consisting of Oregon and the Washington and Idaho territories. Shortly after arriving and beginning discussions, Kientpoos — said to have been goaded to act by some of his followers, including one named Hooker Jim — ordered his party to attack the U.S. agents. Gen. Canby, shot by Kientpoos himself, and one other representative were killed.

Incensed by the killings, the Army launched a second offensive on the stronghold on April 15. Again, their advance was slowed by the difficult terrain and the defensive fire of the Modoc, and again, U.S. casualties were disproportionately high. When the Army forces finally reached the heart of the stronghold two days later, they found that the Modoc had escaped to the south through corridors in the lava beds.

Several weeks of reconnaissance to locate Kientpoos and his group in the beds resulted in occasional surprise attacks by the Modoc, during which they dealt heavy blows to the military and pillaged supplies. But the constant movement of the Native Americans to evade the Army began to take its toll, and dissent grew among some of Kientpoos’ followers. A Modoc attack on an Army encampment at Dry Lake on May 10 proved to be the turning point in the war. The U.S. forces repelled the’ initial Modoc assault and then turned the tables, chasing them from their high-ground on bluffs overlooking the lake.

In the aftermath of this defeat, the Modoc group fractured, with Hooker Jim and others leading a band away to the west, while most remained with Kientpoos. Short of supplies and without the cover of the lava beds, however, both Modoc groups were under constant duress from the Army’s pursuit. In late May, the smaller group finally surrendered, and Hooker Jim and three other Modoc agreed to help track down Kientpoos’ party. At last, on June 1, 1873, after weeks of eluding the Army’s chase, Kientpoos and the remaining Modoc surrendered at Willow Creek, roughly 40 kilometers east of their stronghold in the lava beds.

Following their capture, the Modoc who had been involved in the six-month conflict — including women and children — were treated as prisoners of war and most were sent to the Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma, which had been established in the 1830s. Kientpoos and five other Modoc were tried by a military tribunal — at which they had no legal representation — convicted of assault and murder and sentenced to death. President Ulysses S. Grant later commuted the death sentence for two of the six, but Kientpoos and three others were hanged at Fort Klamath on Oct. 3, 1873.

A sketch of the attack by Kientpoos and his fellow Modoc that left Gen. Edward Canby and another U.S. representative dead. Credit: Library of Congress.

Among the infamous Indian Wars, which lasted from the early 19th into the early 20th century, the Modoc War is remarkable for several reasons. It was the only one in which a U.S. general was killed. And it stands as an incredible example of how terrain can tilt the balance of power in battle. Although able to hold their ground in the rocky lava beds against a vastly larger and better-equipped force, the Modoc ultimately succumbed once they were forced onto more even ground. Most importantly, however, the cost of the war for both sides was extraordinary.

The U.S. spent a small fortune — estimated to have been a half-million dollars — to defeat a relatively small opposition, and in the process lost about 70 soldiers and civilians. Although the Modoc suffered fewer fatalities — about 15 warriors plus an unknown number of women and children — the damage left the tribe’s culture decimated and its remaining members divided in various locations, none of which were on their traditional homeland.

Today, the remaining Modoc are split between two groups. Those who stayed on the Klamath Reservation and did not participate in the war, along with some who returned to the area from Oklahoma starting in the early 20th century, are part of the Klamath Tribes, a federally recognized three-tribe confederation of the Modoc, Klamath and Yahooskin. About 200 descendants of Kientpoos’ band who fought in the conflict are part of the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma, headquartered in Miami, Okla., which was federally recognized in 1978.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.