by Naomi Lubick Tuesday, December 10, 2013

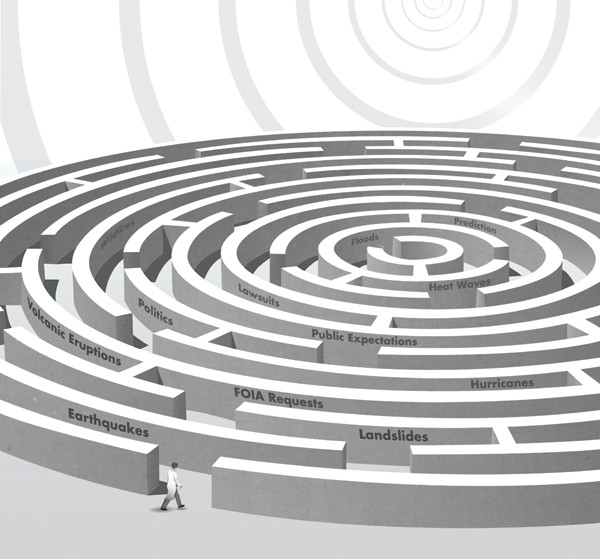

Kathleen Cantner, AGI

Background photo shows a debris flow along a stream triggered by the remnants of Hurricane Ivan in September 2004 in Macon County, N.C. It killed four people and destroyed 16 homes and structures. Left inset: A home close to the stream was destroyed. Right inset: A home set back from the stream was spared. This landslide, along with hundreds of others in the western North Carolina mountains, spurred the legislature to pass the Hurricane Recovery Act of 2005, authorizing creation of the North Carolina Geological Survey Landslide Hazard Mapping Program. The intent of this program was to make people more aware of landslide hazards in the mountains and to provide a tool for planning and emergency management courtesy of North Carolina Geological Survey (NCGS )

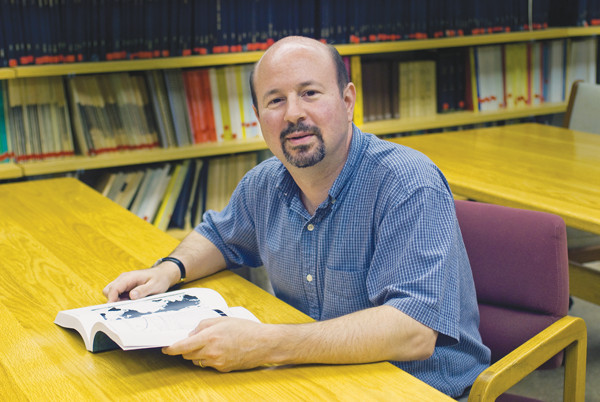

Penn State climatologist Michael Mann recently wrote about legal battles over his research and findings in The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars. Greg Rico, courtesy of Michael Mann

At the 2012 and 2013 annual meetings, AGU offered scientists the opportunity to educate themselves about legal issues by offering access to a "Lawyer in a Box." Kathleen Cantner, AGI

Just over a year ago, in a cavernous room of the Moscone Convention Center in San Francisco, Calif., hundreds of geophysicists, seismologists, volcanologists and climate scientists, as well as a few journalists and a lawyer or two, sat transfixed as a panel discussed the manslaughter conviction of six scientists and a public official in Italy a few months earlier. The Italian scientists and official had been accused of giving misleading advice to the public — failing to communicate the seismic risk, based on their knowledge — ahead of a magnitude-6.3 earthquake in April 2009 in the city of L’Aquila that killed 309 people.

In a question-and-answer period at the end of the presentation, which occurred during the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU), more than a dozen scientists spoke passionately about their fears of prosecution — or persecution, as many suggested — because of their research. After all, if the Italian seismologists were facing jail time, could other scientists also somehow be found at fault for their research, findings and communications?

The L’Aquila case awakened awareness of a relatively new risk in hazards research, one that climate scientists have already been experiencing. Researchers need to communicate their results, but sometimes, their message gets misinterpreted and they find themselves under attack. Whether they are mapping natural hazards, assessing the odds of the next large earthquake or landslide, or gauging the likelihood of an imminent volcanic eruption, researchers know that they are only calculating the probabilities of a given hazard occurring within a certain time period, not making precise predictions. But explaining probabilities is challenging, and clear communication is key. The case in Italy revealed that public perception of researchers’ work might open the researchers themselves up to litigation.

The questions asked by the scientists sitting in the room in San Francisco — and by researchers the world over, in the wake of the conviction of the Italian scientists — were personal: Could I be next? How can I avoid legal issues?

The answers aren’t simple, but researchers, whether in academia, government or private business, usually have some kind of protections available to them. But they have to seek them out and be prepared.

Precise earthquake predictions are impossible, but scientists are always working to improve earthquake probability forecasts. Although the distinction between probability and prediction may seem subtle, or nonexistent, to the public and policymakers, for scientists, there is a world of difference between the two.

At the time of the 2012 AGU meeting, the events in L’Aquila, Italy, were fresh in researchers’ minds. Seismologists often end up working far afield, from Chile to China, India to Indonesia, Japan to New Zealand — anywhere that big earthquakes have occurred, and might occur again. Abroad, scientists might unwittingly get into trouble, sometimes with strange consequences (see sidebar, page 34) and sometimes with potentially serious legal ramifications.

“Every country has its own rules,” says Michael Gerrard, a professor at the Columbia University School of Law who directs the Center for Climate Change Law (he and a colleague laid out some of those rules in the U.S. in an article in Eos in time for the 2012 AGU meeting: http://bit.ly/1ho3ffK). Doing fieldwork in Iowa may be a bit different than doing fieldwork in Namibia, he says, particularly when it comes to liability — and it’s worth checking out the situation, politically and scientifically, before going abroad.

If trouble does arise in the U.S., most scientists — government employees or academics — can count on the backing of their institutions. Rex Baum, a geologist at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Landslide Hazards Program in Golden, Colo., cites the Disaster Relief Act of 1974, which grants some protection to the U.S. government and its employees from liability for geologic hazards warnings. Plus, a federal agency tends to shoulder the burden of a case: For example, a case lodged against a USGS employee might be brought against the agency itself or the Secretary of the Interior. However, sometimes, an employee can be directly named, depending on the nature of the claim, Gerrard says.

“In most cases, the federal government and its employees are immune from liability if they engage in good faith efforts,” he adds. “If you predict wrong, and are acting in good faith, you’re ordinarily not liable in the U.S.,” he says, adding that the rule seems not to have held true for the scientists in L’Aquila.

In a recent letter published in the journal Science, Enzo Boschi of the University of Bologna, one of the convicted scientists, summarized the situation: He and his colleagues explained the region’s seismic risks as best they could, publishing hazard maps and peer-reviewed literature. Though they never spoke directly to the public, a local public safety administrator did. And it was his statements that got the scientists into trouble. Nevertheless, the prosecutor in the case found success with a jury in attacking the scientists.

“The public prosecutor’s superficial interpretation of scientific results to bolster his argument sets a grave precedent for not only seismology but many other disciplines as well. Science is constantly evolving; research proceeds by trial and — as knowledge grows — error,” Boschi wrote. “My question is: What could I do to avoid conviction? I suppose I should have foreseen the earthquake!”

The scientists are currently appealing the conviction, and although there are disagreements about the exact way communication was handled in L’Aquila, the scientists do have the backing of many in the international science community.

The case in Italy is an “outlier,” Gerrard says, and researchers working in the U.S. aren’t likely to encounter such legal action. However, outside of the U.S., the situation is murkier. If scientists work with agencies like the U.S. Agency for International Development, those groups will support the scientists as they communicate with their hosts. At issue, in the end, is the question of liability: Who, if anyone, is to blame for injury, death and damage when disaster strikes?

When property or lives are lost, blame tends to be the main motivation for lawsuits, usually in search of compensation. After landslides, for example, property owners will often try to sue those involved in the development of their property, says Jennifer Bauer, an independent landslide researcher and past president of the Association of Environmental and Engineering Geologists.

That’s largely because the people are trying to offset the cost of the damage, which in most cases is not covered by insurance, says Scott Burns, an engineering geologist at Portland State University in Oregon. Earthquake and flood insurance are usually available in regions at risk, but they don’t cover landslides; landslide insurance, meanwhile, is nearly impossible to get, and prohibitively expensive where it is possible.

Without insurance to buoy them, homeowners end up looking for a culprit to cover damages; thus, lawsuits against landslide specialists are common, says Burns, who has been called to testify in court as an expert witness in landslide cases. However, such cases usually fail, he says. “Lawyers want to say, ‘This is the cause [of the slide],’” Burns notes, “but you can’t do that with landslides because there are lots of causes.” For example, a giant storm might soak hill slopes, leading to slides, or slow creep might turn to failure after a spring melt. Or people build their homes in the outwash of former slides — which created welcoming but treacherous terraces — or in areas where road-building has altered soils and made houses downhill vulnerable.

Modeling natural landslides is difficult enough, Bauer says, but modeling regions where homes have been built on human-altered landscapes is even more so. When she worked for the North Carolina Geological Survey, Bauer mapped all of the landslides she came across, but the susceptibility maps only modeled areas affected by natural slides. As a state employee, she was protected from litigation. Also, her team’s final maps bore legends with large disclaimers, she says, that the maps were for information only, not for specific risks or cost assessments.

Today, Bauer and her business partner run a small consulting firm called Appalachian Landslide Consultants, and the team maps landslides for nonprofit organizations and local governments that apply for grants to support their work. But they also educate people, including both homebuyers and real estate agents, about landslides. Bauer recently made several presentations to real estate agents on how to identify telltale landslide signs on a property, such as nearby trees with curved trunks that have grown to accommodate slumping slopes, or houses with bent deck posts and cracked foundations. Her company carries professional liability insurance, and contracts include a paragraph about limiting liability. Even with such disclaimers, she says, it may not prevent the company from being sued.

One thing that might help, Burns says, is universal insurance that would cover landslides as well as other hazards. New Zealand, for example, requires homeowners to buy policies that cover earthquakes, landslides, tsunamis, floods and just about any other hazard you can imagine, he says, which should be a model for other places at risk. In a way, he says, having that kind of insurance might take the pressure off hazards researchers, shifting it to the insurance companies and others to make the probability assessments for these possible disasters, and reassuring the public that they will not be completely abandoned in a disaster. However, such insurance could also lead to very high insurance premiums or de facto support of risky behavior, such as building in flood plains or other hazard-prone landscapes, Gerrard notes.

Climate researchers have long been familiar with the challenges of communicating risk. For years, they have dealt with the various kinds of attacks that have emerged after reporting their results — everything from huge Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests and libelous attacks in the media to lawsuits and even death threats.

One of the most well-known cases is that of Penn State climatologist Michael Mann. At the time of the 2012 AGU meeting, Mann’s latest trial was wending its way through the courts: He had filed suit in Washington, D.C., courts against the National Review Online and the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a conservative magazine and think tank, respectively, for defamation (that suit was ongoing as EARTH went to press). Earlier, the scientist had been an indirect target of the former American Tradition Institute and Virginia State Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli, who requested Mann’s emails from the University of Virginia, where Mann worked for more than a decade, to support an investigation of possible fraud. Ultimately, a judge ruled that the University of Virginia was not subject to state FOIA law. Mann says he has spent thousands of dollars and a lot of time defending himself, and has written a book about his experience, “The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars.”

With Mann’s story and other similar situations in mind, AGU offered scientists the opportunity to educate themselves about legal issues at its 2012 meeting. About a dozen people took advantage of the first “Lawyer in a Box,” co-sponsored by the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund. A lawyer named Kit Douglass met with worried conference-goers to discuss general legal issues related to possible attacks on their research in climate change and other fields.

Scientists “are very knowledgeable and smart in the area they are working on,” says Douglass, who works for Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), which sponsored the “Lawyer in a Box” again at the AGU meeting last month. “It doesn’t even occur to most people that there could be legal problems,” she says. “It’s not because they are doing anything wrong, but just because of the nature of their work that people try to discredit them.” Douglass says that most researchers “don’t know the legal or political ramifications for their work” if they were to be sued or attacked, nor do they know if their employer will support them.

“The first line of defense is going to be the lawyers for the employer — for the government agency, university, whatever it is,” Gerrard says. They have a stake in defending their employees, Douglass adds. However, that commitment might vary according to institution.

Shortly after the AGU meeting in 2011, Katharine Hayhoe, an atmospheric researcher at Texas Tech University, came under attack by Rush Limbaugh and others for writing a chapter on climate change intended for publication in a then-upcoming book co-edited by Newt Gingrich. Hayhoe found herself served with multiple FOIAs by the American Tradition Institute, and she and her university responded as they were obligated to do by Texas state law.

At first, Hayhoe says, she felt less supported by the university’s legal department: She had never had to deal with them before. Plus, unlike Virginia’s laws, Texas’s laws side on full disclosure, which meant she had to turn over every email requested. But the school’s lawyers offered advice on what might be intellectual property that she could redact under state laws. And when the American Tradition Institute filed a legal complaint stating that the university had not complied with one of the organization’s requests in a timely fashion, the university legal department stepped up its response.

But Hayhoe says she needed not only legal but also emotional and moral support. So she contacted people who had already gone through the kinds of personal attacks that she was experiencing. After hearing what others had been through, Hayhoe says, she thought carefully about how she wanted to respond — “What level of engagement do I think is appropriate? I had to consciously draw my boundaries, which fortified me to act” — and to protect herself from personal attacks totally unlike the kinds of professional scientific critiques to which scientists are accustomed to doling out and accepting.

The L’Aquila case “made a clear point that the public considers it scientists’ responsibility to communicate information on risk, including interpretations of that risk,” Hayhoe says. “It’s ironic,” she says. “When scientists fail to communicate, they can be found at fault, but when they do communicate, that’s when they are attacked.”

For climate scientists, whose work can become lightning rods for public scrutiny, researchers should seek private counsel when feeling concerned or threatened, PEER’s Douglass says. They might also find financial and moral support from the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund. The nonprofit organization was co-founded by Scott Mandia, a meteorologist at Suffolk County Community College in Long Island, N.Y., and Joshua Wolfe, a photographer, filmmaker and co-author of “Climate Change: Picturing the Science.” Together with the support of PEER, the organization has collected money for scientists facing legal challenges (including Mann, on whose defense they have spent tens of thousands already, Wolfe says).

Despite all the challenges Mann has faced, he continues to work, publish and communicate his findings. Bullying, he says, should not stop researchers from speaking about their work, because informed debate requires the knowledge that scientists have carefully accumulated. He encourages scientists not to self-censor, but rather to speak about the extremes, uncertainties and probabilities involved. Mann says he is pleased to see a new generation of scientists — accustomed to digital media — stepping up to communicate their findings to the public.

Scientists — whether they are seismologists, climate researchers or geoscientists working on other hazards — must be free to speak about and do their science, says Alik Ismail-Zadeh, a mathematical geophysicist at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany who is Secretary-General of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG). But it is also scientists’ responsibility to communicate their work to social scientists, policymakers and the public, to make sure that their science is understood and incorporated into policy and public understanding, says Ismail-Zadeh, who has edited a book (to be published by Cambridge University Press in May) intended to tease apart these issues.

How scientists communicate is the key, Ismail-Zadeh says. “Scientists must be brave and tell the public, ‘We don’t know exactly,’ when probabilities are difficult to translate and the unknowns are great.” At that point, he says, the public might ask, “Why do we pay money to you?” Scientists, he says, must answer: “Because we need to make sense of big uncertainties.” His take is to be conservative but communicative, and to focus on the vulnerabilities: Where is a society most likely to be hit in the case of certain hazards? He cites a 2011 declaration from a partnership called Extreme Natural Hazards and Societal Implications, led by the International Council for Science and including AGU and IUGG. The participants suggested creating an intergovernmental panel for disaster assessment (similar to the one on climate change) to help countries identify their vulnerabilities to earthquakes, floods, landslides, hurricanes and more frequent as well as more severe storms that may come with climate change.

For earthquakes and other hazards, the public needs to learn how to understand the probabilities of these relatively unlikely occurrences, Ismail-Zadeh says, in the same way that they understand that the weather forecast does not come with complete certainty. (Meteorologists aren’t held liable for bad forecasts, Gerrard points out.)

Meteorology is a good example of how people have become accustomed to probability-based forecasts for the weather, Ismail-Zadeh says. Through long experience, people know that the weather forecast is only good for about three days — still an amazing feat for meteorologists to have accomplished, and one based on a century of modeling and observations. In the complex and chaotic system that is natural weather, further accuracy past that three-day window becomes increasingly difficult.

The public may never become accustomed to understanding such information in the same way for hazards, says Michael Blanpied, a seismologist at USGS in Reston, Va. People hear about the weather every day, he says, whereas earthquakes are rare, and happen “without any physical warning. They are always surprises — and surprises that people don’t encounter very often.”

People also don’t encounter the scientific process — which includes disagreement among scientists — every day, Blanpied says. Thus the public doesn’t necessarily understand that scientific disagreements are normal. Even where there are top-quality scientists studying earth hazards and occurrence rates, he says, “as scientists, our individual opinions may differ considerably on the nature of earthquake hazard.”

Regardless, “we need to present the best available science to the public,” he says, something the USGS strives to do as an agency. Part of that involves presenting the consensus view, and part involves helping explain complexity.

Perhaps someday, Ismail-Zadeh says, scientists will have enough seismic information to post earthquake probabilities on a daily basis for regions with higher risk, as is done on a very limited basis in California right now. The same might eventually happen for landslides, tsunamis, volcanoes and other hazards, he adds. But until then, researchers have to communicate about the hazards, while making sure they do not put themselves at risk.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.