by Mary Caperton Morton Thursday, August 7, 2014

Credit: drumbo/www.flickr.com via Creative Commons.

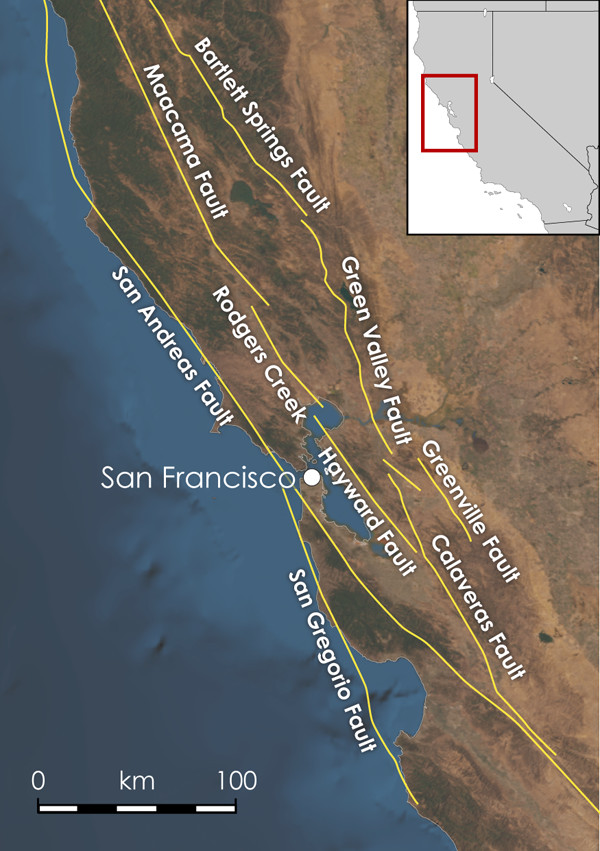

The San Andreas Fault is the most notorious fault in the San Francisco Bay Area, but other principal faults could also pose a significant threat to the region. Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI.

Californians are bracing for when the San Andreas Fault unleashes the next “big one,” but a new study looking at the paleoseismic history of the San Francisco Bay Area suggests that accumulated stress could also be released in a series of moderate to large quakes on satellite faults, rather than by a single great event on the San Andreas.

“Most people are familiar with the 1906 [estimated] magnitude-7.8 earthquake that ruptured a 470-kilometer-long section of the San Andreas Fault,” says Timothy Dawson, an engineering geologist with the California Geological Survey, based in Menlo Park, who was not involved in the new study. “But most aren’t aware of this cluster of earthquakes that happened in the 17th and 18th centuries.”

The San Francisco Bay region straddles the Pacific and North American plates, with accumulated stress distributed among a number of principal faults, including the San Andreas, San Gregorio, Calaveras, Hayward-Rodgers Creek, Greenville and Concord-Green Valley faults, all of which have been fairly quiet since the 1906 event.

“We know these plates are moving,” said David Schwartz, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, also in Menlo Park, and co-author of the study, published in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. “The stress is re-accumulating, and all of these faults have to catch up. The big question is: How are they going to catch up?”

To better understand the earthquake history of the San Francisco Bay region, Schwartz and colleagues excavated a number of trenches across the region’s various faults and radiocarbon-dated the rupture scars left by past earthquakes, extending the paleoseismic record back to the 1600s.

They found that between 1690 and 1776, a cluster of earthquakes with magnitudes estimated to have ranged from magnitude 6.6 to 7.8 occurred on the Hayward Fault (north and south segments), San Andreas Fault (North Coast and San Juan Bautista segments), northern Calaveras Fault, Rodgers Creek Fault, and San Gregorio Fault. Paleoearthquake data for the Greenville Fault and the northern extension of the Concord-Green Valley Fault are still lacking.

“By our calculations and given the geologic uncertainties [in determining magnitudes of pre-instrumental quakes], this cluster of earthquakes released about the same amount of energy throughout the Bay Area as the 1906 earthquake,” Schwartz says, leading the team to propose two models for stress release in the Bay Area: a single, great quake on the main fault, as in 1906, or a series of smaller but sizeable events on the satellite faults.

“Everybody is still thinking about a repeat of the 1906 quake,” Schwartz says. “But what if every five years we get a magnitude 6.8 or 7.2? That’s not outside the realm of possibility.”

A series of large earthquakes could prove to be even more damaging than a single great event, Dawson says. “The last time this cluster occurred, very few people were living in this region. Given the high population density of the Bay Area, if all the major faults start failing individually, each a few years apart, it could be very damaging over a widespread area.”

How this information might change the hazard forecast for the Bay Area is uncertain, says Dawson, who participates in the Working Group on California Earthquake Probabilities, which produces statewide earthquake rupture forecasts. “At this point, we don’t really know how to best incorporate earthquake clustering into our hazard models.”

Forecasts that are more accurate will depend on extending the paleoearthquake record even further back in time, Dawson says, as a few hundred years only represents a fraction of a typical earthquake cycle. “Ideally, we’d like to get 2,000-year-long records for all the faults,” Dawson says. “But it takes a special set of depositional circumstances to be able to retrieve those records, and there just aren’t that many good sites out there.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.