by Timothy Oleson Sunday, July 22, 2012

Let the GEOlympics begin! © Kathleen Cantner

William Smith's 1815 geological map of Britain. public domain

The limestone arch, Durdle Door, along the Jurassic Coast. © Saffron Blaze, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Fingals Cave, a cavernous seacave on the Scottish island of Staffa. © Karl Gruber, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Hutton's Unconformity -- younger, horizontal strata overlying older, upturned layers -- at Siccar Point. © dave souza, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

The thin, glacially carged Striding Edge near Helvellyn Peak in Lake District National Park. © Dominic Donnini

The games of the 30th Olympiad officially kick off today in London. Among the myriad events that draw many of the world’s best athletes, the decathlon perhaps requires more versatility than any other. Over two days, 10 events — from the 100-meter sprint to the long jump to the pole vault — test competitors’ speed, strength, agility and endurance.

Befitting Britain’s diverse landscape — both above- and below-ground — and its history as the birthplace of much of modern geology, I've come up with a decathlon of must-see geological sites across the host country. If you find yourself in the United Kingdom during the Olympics, or anytime for that matter, you can’t go wrong with this list as a base for your travel itinerary. Fair warning, though: It might take more than two days to complete this decathlon.

Naturally, it was difficult to choose just 10 sites when the possibilities abound. If you have favorites, either from among the locales mentioned here or that we’ve left off the list, let us know on Facebook or on Twitter (@earthmagazine) with #earthmaggeolympics.

Now, it’s on to the events! On your mark, get set, go…

On loan to the Tate Britain through October of this year, the original copy of Smith’s 1815 map is usually on display at Burlington House, home to the Geological Society of London. The map was the first large-scale (and largely accurate) depiction of the various rock strata and terranes underlying and outcropping across the British landscape. It helped illustrate the argument — very controversial at the time, even among scientists — that Earth was substantially older than commonly thought. Smith, who was not recognized for his scientific contributions until late in life, is now counted among the greatest British geologists; his life is documented in Simon Winchester’s 2001 biography entitled, “The Map that Changed the World.”

The imposing and iconic cliffs, which plunge from heights of up to 110 meters into the English Channel in the southeast of England, are made of the carbonate remains of Cretaceous-aged plankton. When the plankton died, their shells sank and accumulated as thick layers on the seafloor. The layers were compressed over time into soft, albeit lithified, chalk, which was eventually uplifted and exposed above sea level.

This UNESCO World Heritage Site stretches roughly 150 kilometers along England’s south coast. Despite its name, the ages of the exposed rock along the Jurassic Coast span the Mesozoic from the 250-million-year-old Triassic red mudstones and sandstones at Orcombe Point (near Exmouth) to the 65-million-year-old Cretaceous chalks of Old Harry Rocks (near Bournemouth). From one end to another, there are more than enough fascinating sites — including the Beer Stone, the fossil-rich cliffs of Lyme Regis and the picturesque Lulworth Cove — to make a decathlon out of just the Jurassic Coast alone.

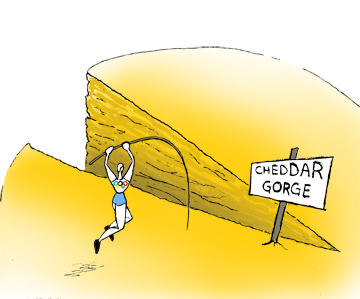

Britain’s largest gorge, Cheddar Gorge, was gradually cut through nearly pure Carboniferous-aged limestone by flowing water. From rim to floor, the gorge’s green grass-covered walls descend about 140 meters. Visitors — of whom there are roughly half a million each year — can drive through the gorge on their way to the town of Cheddar, stop to rock climb and hike, or explore some of the many stalactite- and stalagmite-laden caves. (In 1903, Britain’s oldest-known complete human skeleton, dubbed Cheddar Man and thought to be about 9,000 years old, was found in Gough Cave.) Don’t forget to stop in at a cheese shop for a bit of local flavor.

Also known as the National Showcaves Centre for Wales, this Welsh tourist hotspot boasts spectacular cave features carved, as at Cheddar Gorge, into Carboniferous limestone. Much of the more-than-10-kilometer-long cave system, which is still forming, is only open to experienced spelunkers. But self-guided walking tours of the eponymous Dan yr Ogof Cave, Cathedral Cave and other accessible areas still cover more than 1 kilometer and take visitors past impressive features like massive flowstones, floor-to-ceiling pillars and something called the Flitch of Bacon (take a virtual tour here to read about it). Many archaeological artifacts and bones have also been unearthed at the site.

You’ve made it through half the events, and you deserve a rest. Why not stop in Bath and do as the Romans famously did: Spend some time relaxing in a naturally heated spring-fed spa. The warm water originates as rain falling on the nearby Mendip Hills. The rainwater seeps through the ground to depths of several kilometers where it is geothermally heated to about 80 degrees Celsius. Don’t worry though, by the time the water percolates back up to the surface, it has cooled into the 40s.

Both famed for their magnificent columnar jointed basalt, these two sites are linked by the legend of Finn MacCool, an Irish warrior who is said to have built a causeway between Ireland and Scotland. The distinctive jointing in the basalt formed as Early Paleogene lavas cooled. Situated on the northeast coast of Northern Ireland, the 38,000 columns of Giant’s Causeway — a UNESCO World Heritage Site — form a bizarrely blocky landscape that rises and falls in stepwise fashion. When you’re done there, make the long jump (or take a boat tour) over to the uninhabited island of Staffa off the rocky western coast of Scotland. Basalt columns form the base of the cavernous Fingal’s Cave, a sea cave famed for its cathedral-like acoustics that have lured many renowned artists. Felix Mendelssohn was inspired to write his Fingal’s Cave overture after he visited the site in 1829. (*Although not technically in Great Britain, Northern Ireland is part of the United Kingdom, so I think it's fair game.)

James Hutton, known as the father of modern geology, was instrumental in formulating the fundamental geologic tenet of uniformitarianism — that understanding Earth as it is presently is the key to understanding how it came to be that way — among other major contributions. Upon visiting the seaside Siccar Point on Scotland’s east coast in 1788, Hutton interpreted the distinctive unconformity in the rock — vertically upturned layers of Silurian graywacke overlain by horizontal strata of Late Devonian red sandstone — as clear evidence of the tremendously slow nature of geologic processes, and hence of Earth’s old age.

Covering nearly 2,300 square kilometers, the Lake District is home to a lush, sparsely developed landscape and a host of natural features that draw close to 16 million visitors each year. Five hundred million years' worth of geology is on display, from the Cambrian-aged Skiddaw Slate to outcrops of Devonian granite (at Eskdale, for instance) to the glacial valleys and arêtes carved by successive glaciations in the last few million years. The deep, sinewy lakes and high-elevation tarns that give the park its name are home to abundant wildlife and offer many recreational opportunities, as do jagged volcanic mountain peaks, or fells, like Helvellyn and Scafell Pike, England’s tallest.

The seaside town of Whitby, situated at the mouth of the River Esk and surrounded by North York Moors National Park, has a rich heritage as a fishing and maritime port and, notably, is where renowned explorer Captain James Cook first took up seamanship. As its coat-of-arms — which bears three ammonites over a striped field — attests, Whitby is also well-known for the fossil-rich layers of Jurassic-aged clay, shale and sandstone that are exposed and continually eroded at the river’s mouth. The 19^th^-century popularity of jewelry made of jet — the black, lustrous remains of fossilized trees preserved in the same rocks — again put Whitby on the map. If you’re looking for a break from fossil hunting, and if you dare, you can visit the grounds of St. Mary’s Church, said to have inspired scenes in Bram Stoker’s "Dracula."

Last not but not least, Creswell Crags is an archaeological and paleontological playground where the remnants of inhabitants — Neanderthal, modern human and animal — from the past 50,000 years have been uncovered. Like Cheddar Gorge, Creswell Crags features a large limestone gorge and a network of caves — Church Hole, Robin Hood’s Cave and Mother Grundy’s Parlour among them — carved gradually by flowing water. In the last decade, the only known cave art in Britain has been found at Creswell Crags and dated to about 15,000 to 13,000 years ago.

Well, you’ve made it to the end of EARTH’s geologic decathlon through Great Britain. Whether you actually traveled to all these destinations, or if you just read through the descriptions, you deserve congratulations and a well-earned rest. We hope you enjoyed the journey!

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.