by R. Tyler Powers Friday, September 21, 2012

Statoil

The author, R. Tyler Powers, in front of a drilling rig in the Bakken oilfields. R. Tyler Powers

The author, R. Tyler Powers, at work inside an office trailer. R. Tyler Powers

Lengths of drill pipe at an oilfield near Williston, North Dakota. Lindsey Gee, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic

Williston North Dakota in 2008, when the population was somewhere between 12,000 and 14,000. Copyright Andrew Filer, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic

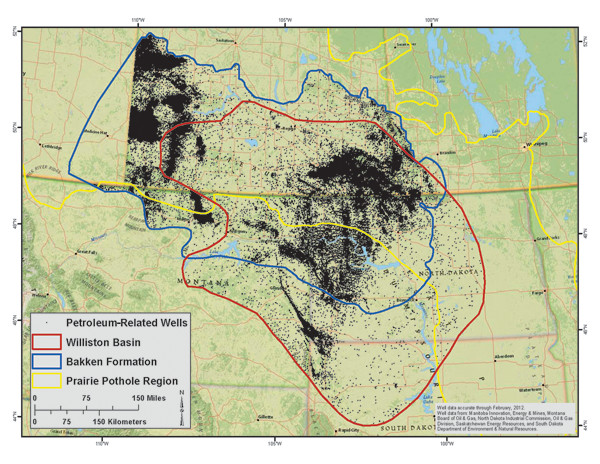

Black dots indicate wells drilled in the Bakken Formation, Williston Basin and larger Prairie Pothole Region, as of February 2012. U.S. Geological Survey

Like many of my colleagues, I have found myself in awe of the drastically changing energy landscape around me. Both technologically and economically, the world of energy is not what it used to be. Precious resources that allow the modern world to exist are becoming harder to find and much more difficult to extract, but advances in drilling technology, such as directional drilling, are a tribute to humanity’s ability to innovate when needed. Nowhere on Earth is this more prevalent than in the Bakken Formation of North Dakota, where I have spent the last year working, learning, living and observing as the energy world changes.

After finishing my undergraduate work at the University of Wyoming in 2010, I found myself wondering what was next. The U.S. economy was in shambles and the job market was dismal. I was 26 with no job, wife or kids. All I had was a head full of raw knowledge and a diploma declaring that I knew a thing or two about how the Earth worked. After years of study, I felt confident in my ability to understand the geologic processes shaping the world around me, but I didn’t have the first clue about how to turn this knowledge into a career.

As fate would have it, I was offered a job in my native central Florida investigating sinkholes for insurance companies. But after less than a year back home, I began to catch wind of how many of my college brethren were taking advantage of the oil and gas boom occurring in North Dakota. I heard stories of geologists earning double or triple what I was making, and living a playboy lifestyle with weeks off at a time. A few phone calls later and without even a single application submitted, I found myself driving across the country with dollar signs in my eyes and all of my possessions in the back of my SUV. Just how much my life was about to change was anyone’s guess.

Finding work was easier than expected. A simple inquiry on Facebook revealed half a dozen college friends working in the oilfields, all of whom indicated that their companies were seeking young geologists. A week after submitting my résumé, I was interviewing in Billings, Mont., for a well-site geologist position. After an hour-long interview and a couple of beers over lunch, I was told to report to Williston, N.D., in early December for training.

A few short months later, I found myself sitting in a trailer in the shadow of a multimillion-dollar oil rig, staring at a cluster of computer screens that couldn’t have been more confusing had they been in Greek. From the highway, the rig appeared as a beacon of hope for the future of domestic energy and American oil independence. But inside the work trailer it was a bit of a different story.

Diesel-soaked clothing, the constant groaning of the rig, heavy equipment to evade and 90-hour work weeks were the immediate hurdles that had to be negotiated while working and living not a hundred meters from the rig for up to two months at a time. This was certainly a far cry from the comfortable 9 to 5 work day I had become accustomed to in Florida, but the promise of quick fortune extinguished any lingering doubts associated with the work conditions. In addition, before long, I found a strong sense of pride in the hard work and long hours I was putting in with my colleagues in the oilfields. The last hurdle I had to pass in becoming comfortable as a well-site geologist was safety. This job can be dangerous: The equipment is enormous. The 10-hour OSHA training required to become a well-site geologist quickly became the cornerstone of self preservation. Thankfully, safety has become the primary goal these days, even above production, and after a short while the scene grew less intimidating.

Once I got over the initial adjustments and challenges of the first few months, I found that the life of an oilfield geologist suits me well. I enjoy being responsible for a multimillion-dollar operation and appreciate the trust bestowed upon my fellow geologists and me by our superiors.

Our work is exciting too. My colleagues and I are responsible for a number of critical observations while “on tower,” which is oilfield slang for being on a shift. We geologists have the help of an engineer known as an MWD (measurement well-drilling person) and a directional driller, the person responsible for adjusting the angle of inclination at which the bit is drilling. From the comfort of a trailer, we monitor gas from the mud being circulated through the well, use gamma radiation markers to indicate where we are in the rock formations and, of course, examine rock samples from the various strata through which we drill. Using the information gathered, we can accurately navigate through the various strata until we reach the Middle Bakken — approximately three to four kilometers below the surface — at an angle near 90 degrees relative to the surface. After “landing the curve,” lateral or horizontal drilling proceeds for an additional 3,000 meters until TD, or total depth, is reached. Once we reach TD, the well is ready for hydraulic fracturing and potentially decades of oil and gas production.

Due to the inconsistent nature of the Bakken, caused by varying depositional environments and the extreme conditions the equipment is expected to endure, the drilling work can be tedious and highly frustrating. Often, an indicator rock layer within the Bakken is used as a guide to help navigate during lateral drilling, but these layers can simply disappear or pinch out, leaving geologists flying blind until another indicator can be determined. Even more exasperating are equipment failures. Any failure within the system, whether it is with the gamma monitoring tool or the drill bit itself, necessitates a “trip,” meaning all the pipe must be pulled out of the ground. The tripping process is lengthy, often taking several days, and can add weeks to the drilling project.

Despite these struggles and frustrations, I find the work to be a constant and rewarding challenge. There are few better feelings in this world than a job well done, especially after that job has kept us secluded for more than a month and we’re released back into civilization with cash lining our pockets.

Civilization is something that you begin to truly appreciate when you have been living in a “man camp” for several weeks at a time. That said, Williston, N.D., unfortunately does not resemble what this city boy, raised in Tampa and Orlando, considers civilization. Williston is a remote place. Even a small city such as Laramie, Wyo., where I lived for four years during college, seems like a metropolis compared to Williston. I must admit, however, that although the infrastructure was designed for the roughly 14,000 people living there in 2011 (according to the U.S. Census Bureau), the town manages to adequately support the estimated 100,000 people now living and working in the region.

Housing in town is next to impossible to find, so most oilmen live in man camps. These camps are nothing more than rows of trailers — usually 50 to 100 meters from the rig — provided by the oil companies for roughnecks, geologists and other company workers. Sometimes we are only a few minutes’ drive from town, whereas at other times we might be an hour from any significant population.

The conditions and living circumstances vary drastically from company to company. Admittedly, the geologists have it better than the roughnecks who are typically crammed into trailers like sardines. Rarely do we geologists have to share a bedroom in the two-person trailers, although sometimes we do share a modest kitchen and bathroom. Everyone is expected to cook for themselves, so diets vary drastically. The trailers are typically in good condition, and are certainly comfortable enough considering they are free, but they can get cold during a brutally frigid North Dakota winter night. I brought my own sheets, pillow, clothes, food and guitar, so I manage to be quite comfortable.

The bare necessities are sufficient in Williston, by and large. But there are occasional shortages of just about everything, including gasoline — ironic considering how much oil there is in the area. And stores tend to run out of fresh produce and meats quickly, especially in winter. You’d better make a good list and plan your shopping trips to Walmart carefully, because no matter what you need — even if it’s just toilet paper — you can count on standing in line for an hour during the day.

When we do leave the trailers and go into town, there are modest, albeit limited, options for entertainment. Because of the huge influx of people, however, the average wait at any restaurant will be on the order of an hour — sometimes longer — every night of the week. Time is easily passed though, because Williston is never in short supply of interesting characters, most of whom are more than willing to entertain you with casual conversation.

In Williston, I have met people who hail from Florida to Alaska and everywhere in between. Their occupations range from oilmen to truck drivers, from bricklayers to traveling salesmen and even exotic dancers, whom I’ve heard (through the grapevine, of course) can make more money in Williston than Las Vegas. The characters that make up the cast in Williston are as diverse as any metropolitan area I have ever witnessed, leading to an array of opportunities and even a certain element of danger.

My only reference frames for past boomtowns are movies about the old Wild West (it certainly does remind me of that) and stories my father, also a geologist, told. He worked in the same region during the mining boom in the 1970s and spent time in Colorado, Montana, North Dakota and Wyoming. Over the years, he has treated me to stories that paint a vivid picture of how the world of exploration geology used to be. The most infamous place he visited during the ’70s was Rock Springs, Wyo. From what he has said, and from what I learned of the history of Wyoming, the lawlessness of Rock Springs — which included prostitution, gambling and the murder of several police officers — harkened back to similar conditions experienced in the boomtowns of the 1800s. Although such mayhem may not be witnessed in modern America again, there are certainly parallels that can be drawn between that period and the current boom in North Dakota.

With such an influx of people, it’s no surprise that the police have had a hard time dealing with the increase in crime. Every month, radio announcements note that someone has gone missing or that there is a new fugitive on the loose. However, it appears for the most part that as long as you don’t go looking for trouble, it is unlikely to find you.

As with the interesting characters, there is no shortage of seedy types in Williston, but a polite nod of the head in passing generally keeps conflict at bay. There seems to be an unspoken rule among the many varied sects in Williston that honors the idea that although the environment is less than ideal, we are all here to work so we may as well get along.

I have quite enjoyed Williston’s populace: People are quick to buy you a drink and share a laugh if you’re the type of person who can enjoy the company of a diverse crowd. On break from the rig, I often find myself being treated to “big fish” stories from interesting individuals from around the country. Once the food and drink have been consumed, everyone parts ways with no intention of meeting again; but the single-serving camaraderie of unfamiliar people can be a breath of fresh air after long stints in the field.

Understandably, locals’ opinions of the sudden development are mixed; many are positive, others are resistant to the changes. The boom has brought a tremendous amount of money into Williston. The infrastructure has grown to accommodate the massive influx of people, and overall the town has thrived. Those who lament the changes often focus on the crime and the unending buzz of traffic and people in the town. Many claim that their small town has been transformed — for the better according to some, who hope for the growth to continue. Others wish for the town to return to the way it was. But even they realize that things will never be the same. This boom will likely persist for several years or decades.

The Bakken is a very large formation, and new wells open daily, encouraging more and more people to make their way to far northwestern North Dakota. In 2008, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimated that the Bakken Formation contains anywhere from 3 billion to 4.3 billion barrels of oil that is technically recoverable within the boundaries of Montana and North Dakota. At current market prices, these reserves are worth somewhere between a quarter and a half trillion dollars. USGS is currently reassessing the formation (due out in fall 2013); industry estimates put the reserves at somewhere closer to 10 billion to 20 billion barrels of oil.

It seems pretty clear that as long as the price of oil is high, the work will continue. Based on the billboards around town advertising openings for roughnecks, the oil companies appear to be optimistic for the continuation of drilling. Most wells produce oil for decades, making profit a virtual guarantee. The initial investment is large but the return is far greater, and based on that model, the current boom will continue to gain strength.

In such uncertain times, much of our country’s youth has found it incredibly difficult to locate employment even with a college education. So the Bakken Boom has truly been a godsend for my generation of geologists. We have not only discovered that our education was worth every penny but that we have been fortunate enough to graduate at a time when our services are at a premium. This opportunity will certainly not last forever, but the majority of my colleagues agree that this boom will be an excellent stepping-stone for our geologic careers. Earth provides us with an amazing array of gifts, but at some point we will reach the end of these resources. It will be the responsibility and challenge of my generation of geologists and all scientists to envision and construct a world that conservatively and efficiently uses these resources to their fullest potential.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.