by Iain Willis Wednesday, July 13, 2016

In "Chichester Canal," British painter J.M.W. Turner's sunset glows with an ethereal quality that is attributed to volcanic aerosols in the skies across northern Europe during the "year without a summer" caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815. Credit: Tate Museum, London/Art Resource, NY.

I had a dream, which was not all a dream. The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars Did wander darkling in the eternal space, Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air; Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day.

“Darkness,” a poem written by Lord Byron in July 1816, is believed to have been inspired by the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia the previous year. That eruption, following on the 1812 eruptions of La Soufrière in the Caribbean and Awu in Indonesia and the 1814 eruption of Mavon in the Philippines, caused significant climatological impacts across Europe — resulting in 1816 being referred to as “the year without a summer.” The volume of sun-blocking ash and aerosols from the eruptions was so large that average temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere dropped by half a degree Celsius. The stratospheric aerosols blocked sunlight, which caused widespread crop failure and famine across great swaths of Europe and North America. Sunsets were vivid red; days were dimmed. This poem was but one of many works of art and literature inspired by the darkest days of 1816.

Perhaps the best-known work of literature to come out of the volcanic summer is the story of “Frankenstein” by Mary Shelley. Shelley, née Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, wrote the book following a dreary summer in Switzerland when she was forced to stay indoors due to the terrible weather. A competition ensued among her party (including future husband Percy Shelley and family friend Lord Byron) as to who could write the scariest story.

Among the other artists thought to have taken inspiration that year was British painter J.M.W. Turner. In paintings such as “Chichester Canal,” Turner’s sunsets are incandescent. The background glows with an ethereal quality that is attributed to the occurrence of volcanic aerosols in the skies across northern Europe.

In recent years, scientists and historians have been able to not only contextualize past eruptions but also more fully understand their far-reaching consequences on art and literature. What follows are a few highlights of how volcanoes have shaped our culture and artistic heritage.

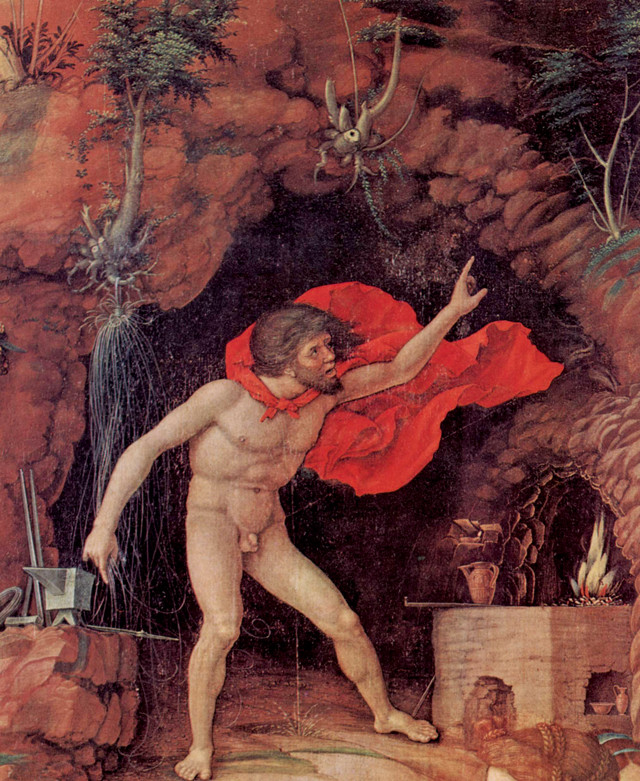

Vulcan, as imagined by Italian artist Andrea Mantegna in 1496. The Romans believed the volcanic island of Vulcano off the coast of southern Italy was the chimney of Vulcan, their "god of fire." Credit: public domain.

Some of the earliest art related to volcanoes are religious works and relics. The Romans believed the volcanic island of Vulcano off the coast of southern Italy was the chimney of their “god of fire,” Vulcan. Eruptions of lava and ash were seen as products of Vulcan’s labors as he crafted thunderbolts and weapons for fellow Roman deities. In honor of Vulcan, the Romans produced numerous paintings, statues and stories befitting their colossal blacksmith.

Across the Atlantic, the Tetimpa people of Puebla, Mexico, were sculpting miniature effigies of Popocatépetl, the volcano that loomed high above them and that they worshipped. Between 50 B.C. and A.D. 100, Popocatépetl was very active, and it’s likely that the sculptures were gift offerings meant to appease wrathful spirits.

The religious and symbolic influence of volcanoes has not dissipated to this day. In Sicily, local priests and parishes still parade around effigies and religious relics when Mount Etna reactivates. And in Quito, Ecuador, many locals believe that the nearby volcanoes are spirits, and that neighboring volcanoes are family relatives of each other. Eruptions are seen as acts of frustration among the spirits regarding the local population’s morality.

Between 1774 and 1780, English painter Joseph Wright of Derby created some 30 paintings of Vesuvius erupting, including the famed "Vesuvius from Portici," even though he never actually saw the volcano erupt. Credit: ©courtesy of the Huntington Art Collections, San Marino, Calif..

In the 1820s, Japanese painter and printmaker Katsushika Hokusai produced a series of images entitled "Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji," printed in postcard format using the characteristic ukiyo-e style of woodblock painting — an homage to Mount Fuji. Credit: all: public domain.

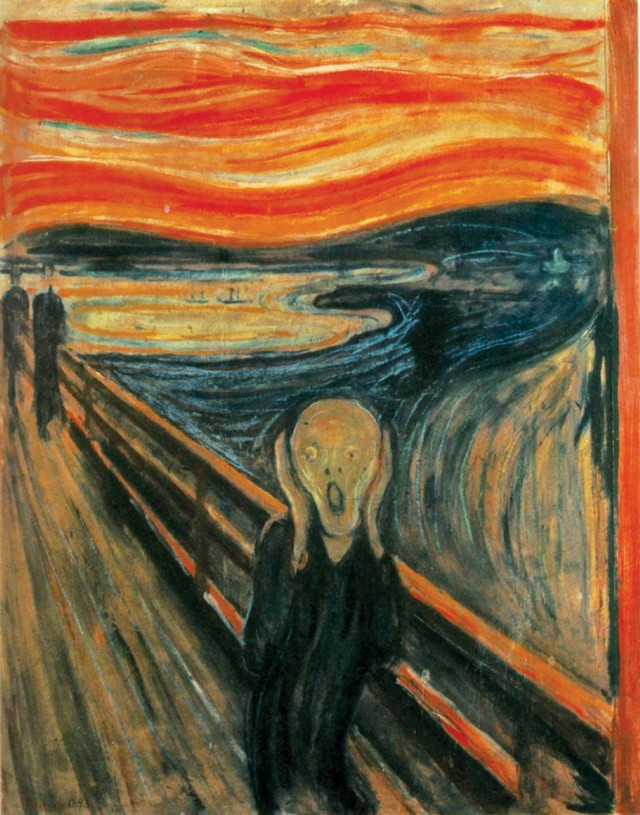

The blood-red skies in Edvard Munch's series of "The Scream" paintings may have been inspired by the Krakatoa eruption in 1883. Credit: public domain.

The Tigua people of Ecuador create bright and vibrant images of Andean life among the volcanoes in various media, including textiles and sheepskin. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/piccaya.

Volcanoes have for centuries been the subject of landscape artists seeking to master their craft. Between 1774 and 1780, English painter Joseph Wright of Derby created the famed paintings “Vesuvius from Portici” and “Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples,” among others of Vesuvius, paintings that remain particularly evocative of how violent volcanic eruptions can be. These visceral representations of Vesuvius erupting show a heavenly torch of light issuing from the volcano, conveying the magnitude of an eruption; and the precision of the paintings served to educate many regarding the nature and scale of the hazard. The irony of Wright’s cataclysmic paintings is that they were largely a product of his imagination. Although Wright visited Italy and stayed in Naples for a spell in 1774, and made sketches of the volcano, he would not have actually seen the volcano erupting as his visit coincided with an inactive time in the volcano’s history. Nevertheless, the paintings are a masterpiece in the portrayal of light.

A half-century later, Katsushika Hokusai, the Japanese painter and printmaker, gained notoriety for his images of the iconic Mount Fuji. In the 1820s, Hokusai produced a series of images entitled “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.” Printed in postcard format using the characteristic ukiyo-e style of woodblock painting, these images remain popular today. (“The Great Wave” is probably the most famous of these paintings.) Not only do these paintings convey the monumental size of Fuji, which is visible from almost anywhere in Tokyo on a clear day, they also pay homage to the Japanese love affair with this volcano. Hokusai’s work depicts a beauty and simplicity in traditional Japanese life. Ever-present in these images of fishermen, farmers and gentry is the large composite cone of Fuji. For the most part, the pictures eschew realism, but they do serve to capture the romance of a volcano believed in Japanese legend to house the source of eternal life. Hokusai’s work was influential not just in Japan but outside the country as well. His style became increasingly fashionable in the rapidly industrializing Europe of the 19th century. The movements of Impressionism, Art Nouveau and Modernism were all inspired by Hokusai’s work, with Monet and Renoir, among many others, becoming avid followers.

Later in the 19th century, the massive August 1883 eruption of Krakatoa in Indonesia also featured prominently in some paintings. British painter William Ashcroft painted vivid red sunsets in November 1883. And, although heavily debated, researchers have theorized that the blood-red skies in Edvard Munch’s series of “The Scream” paintings were directly related to the Krakatoa eruption, even though the works were painted a decade later.

It is not just from antiquity that we witness the artistic influence of volcanoes. The Tigua people of Ecuador show us that volcanic painting is still going on today. These indigenous artisans live among some of the country’s most explosive volcanoes. Despite this seemingly perilous existence, the Tigua continue to paint bright and vibrant pictures of Andean life among the volcanoes. Their paintings, traditionally on sheepskin, are a reminder that volcanoes are part of the everyday tapestry of life: Volcanoes are seen as less of a constant hazard, and more as part of the backdrop of the lives of the Tigua. Following the eruption of Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull in 2010, Scottish poet Dame Carol Ann Duffy was compelled to write the poem “Silver Lining” about the enormous disruption that the volcano caused.

Five miles up, the hush and shoosh of ash, yet the sky is as clean as a wiped slate– I could write my childhood there. Selfish to sit in this garden, listening to the past– a gentleman bee wooing its flower, a lawnmower– when grounded planes mean ruined plans, holidays on hold, sore absences from weddings, funerals, wingless commerce. But Britain’s birds sing in this spring, from Inverness to Liverpool, from Crieff to Cardiff, Oxford, London Town, Land’s End to John O’Groats; the music silence summons, that Shakespeare heard, Burns, Edward Thomas; briefly, us.

Over the millennia, volcanic eruptions have provided lush soils on which civilizations developed, and they have destroyed civilizations as well. They have governed religions, inspired art, and have had significant effects upon our climate and our psyches. It’s inevitable that volcanoes will continue to influence the course and nature of our lives. In the same way these colossal formations have shaped the physical world, they will no doubt continue to influence our cultural and artistic heritage.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.