by Carolyn Gramling Thursday, January 5, 2012

An ammonite in acrylic paint. Peter Bond

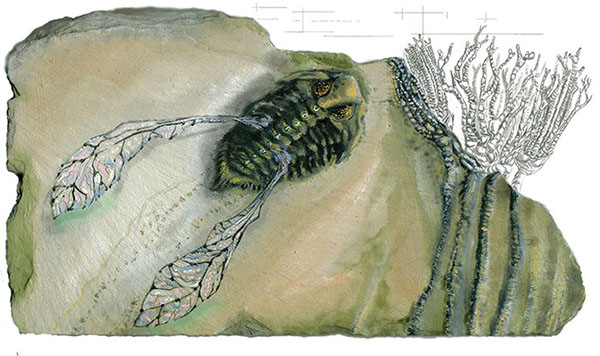

Paleo-artist Glendon Mellow's imaginary flying trilobite. Glendon Mellow

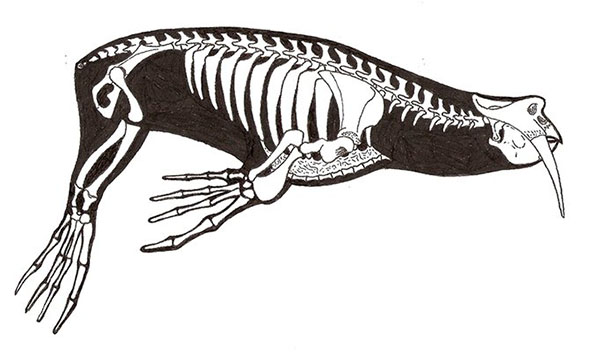

If the Permian-Triassic extinction had never happened, land-dwelling synapsids might have remained dominant - and new creatures such as the 'walrodont' might have evolved. Zachary Miller

Lillian the Albertosaur strolls through the halls of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, glancing sideways at the skeletal model of a T. rex. She’s much prettier than the skeleton, from her textured brown skin, adorned with bright purple spots, to her slightly superior smirk. Neither dinosaur is actually alive: One is a fossil, and the other is a computer graphic superimposed on a photograph of the actual museum. But somehow, Lillian does liven the place up.

And that’s what Lillian’s creator, paleo-artist Craig Dylke, says he was going for. Dylke isn’t a professional artist, nor is he a scientist; he teaches science to kids (sometimes with the aid of a T. rex puppet named Traumador). But he says his computer graphic renderings of prehistoric animals — often plopped down in the middle of the modern world, like Lillian in the museum — serve as a reminder of the wonder and variety of life.

“I enjoy the idea of bringing back long-dead life forms,” Dylke says. “With the medium of 3-D computer graphics, it is possible to recreate renditions that could be mistaken for the real thing, and that’s my goal.”

Dylke is the author of several blogs, including one he “ghostwrites” for Traumador, who is currently trying to make a living in Dunedin, New Zealand (where his creator also resides). But, Dylke says, though dozens of well-known blogs exist about the technical and scientific aspects of fossils — attracting large numbers of professionals and enthusiasts alike — “paleo-artists were sadly underrepresented in this greater paleocommunity.” Paleo-art, he says, “is a very specialized niche, not just in the art world but also in the world of paleontology. There were a few of us trying to make our presence noticed, but the majority of us acted and blogged independently.”

To bring the community together, earlier this year, Dylke and Peter Bond, a blogger, science teacher and amateur paleo-artist based in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, founded the online community ART Evolved, inviting similarly inclined paleo-artist bloggers to join. “I’ve been blogging for about four years or so, meeting people online, commenting on stuff,” Bond says. “Craig and I sat down one night and said it’d be cool if we got some sort of central thing to collaborate on.”

ART Evolved is a place for lifelong dinosaur enthusiasts: The two things its members share are a fascination with dinosaurs — usually going back to early childhood — and an inclination to daydream about how to visually resurrect dinosaurs and other long-since-vanished creatures, complete with skin colors, feathers and movements.

To do this, the paleo-artists use the scant information scientists have on what these creatures looked like as a common jumping-off point. But where they go from there can be quite diverse, with a range of artistic viewpoints that lead to everything from the straightforward sketches of the horned triceratops-like Styracosaurus albertensis by paleontologist Manabu Sakamoto of the University of Bristol in England, to the bat-like, flying trilobites dreamed up by Toronto, Ontario-based artist Glendon Mellow.

There’s been a great deal of enthusiasm, Dylke says. “We’ve all wanted to belong to a bigger circle of like-minded, creative people.” Although they may be amateur artists and scientists, the paleo-artist community tends to know its stuff. ART Evolved is a place where these artists can discuss the details of anatomy or restoration, comparing notes on both scientific studies and the how-to’s of drawing and CGI rendering. Dylke says that ART Evolved’s greatest success is the Time Capsule, a bimonthly challenge (open to anyone) based on a theme (for July and August, it was pterosaurs) that provides a focus for both art and discussions.

Other members propose “what-if” alternate universe scenarios, such as what sort of creatures might have dominated the world instead of dinosaurs had the Permian-Triassic extinction never happened 252 million years ago. (Paleo-artist and science teacher Zach Miller of Anchorage, Alaska, suggested synapsids, a reptile-like group of animals that included the ancestors of mammals and were abundant in the Permian; he then came up with his own creations, such as a walrus-like “walrodont.”)

Imagining such scenarios in the absence of more information is a lot of the appeal of paleo-art, Bond says — but of course, he’d still like to know what dinosaurs really did look like. “I’d love to have a time machine and go back — although it would make ART Evolved obsolete,” he says. “Like, ‘Oh — they’re all green. OK, back to work.’”

For Dylke, livening up the real world remains part of the appeal, however. “I find the idea that everything was different in the prehistoric past really neat,” he says. “The squirrel outside my window would be replaced by a tiny raptor in the Cretaceous, or some sort of arthropod in the Devonian. Not to mention the changes in the plants, climate, landscape. … It makes the dull, boring world around us have the potential to be a totally alien place.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.