by Timothy Oleson Wednesday, December 3, 2014

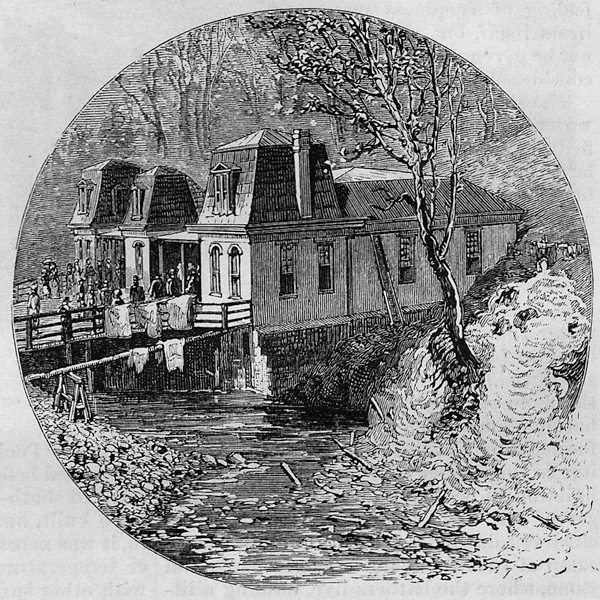

Published in the second volume of George William Featherstonhaugh's "Excursion Through the Slave States" in 1844, this lithograph depicts Hot Springs in the mid-1830s. Lining Hot Springs Creek are a few small cabins in the center of the image and, at right, natural formations of calcium carbonate called tufa. Credit: National Park Service, Hot Springs National Park Collection.

In March 1872, not long after William Henry Jackson’s photographs from the famed Hayden Geological Survey first introduced the U.S. populace to the rugged majesty of northwestern Wyoming, President Ulysses S. Grant designated Yellowstone as the country’s first official national park. Some 40 years earlier, however, a comparatively small plot of land in Arkansas had garnered a similar designation, albeit in different terminology, from then-President Andrew Jackson.

In the early 1800s, the mineral-rich, geothermally heated and ostensibly curative waters bubbling up at the base of Hot Springs Mountain, about 80 kilometers southwest of Little Rock, Ark., had been attracting European settlers for more than 200 years and Native Americans long before that. Amid its growing popularity and at the behest of the Arkansas Territorial Legislature, Jackson claimed a 10-square-kilometer area around the springs as a “federal reservation” in 1832, thus setting it aside for public use and nominally prohibiting private ownership of the land.

After that designation, both the park and the city of Hot Springs, Ark., which grew up intertwined with the park, underwent many transitions. For patients and visitors seeking a regimen of soothing natural baths, it remained one of the foremost destinations in the United States — along with others such as Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and White Sulphur Springs, W.Va. — until the practice of taking curative baths began to wane in the mid-20th century. But Hot Springs National Park — as it was officially designated in 1921 — is still popular with tourists looking to immerse themselves in its architecture, its history, and, thanks to the area’s distinctive geology, its inviting waters.

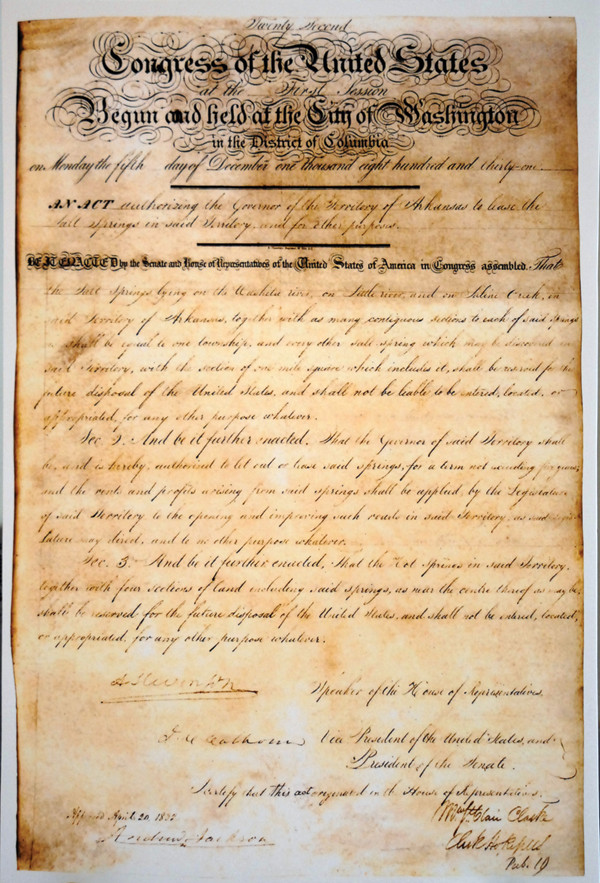

A reproduction of the 1832 act of Congress that designated Hot Springs, Ark., as a federal reservation. National Park Service.

Long before the arrival of Europeans to the American Southeast, the parcel of land that was to become Hot Springs National Park was held sacred and frequented by various Native American tribes. Along with the surrounding mountains, the “Valley of the Vapors” — as the narrow gap between Hot Springs Mountain and West Mountain where the springs emerge was known — was, according to custom, a peaceful refuge for all where weapons and conflict were forbidden.

The Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto and his party are thought to have been the first Europeans to encounter the springs, as diary entries from their trek in 1541 speak of warm streams and brackish pools in the vicinity. For the next two and a half centuries, Spain and France made alternating claims over the area, still largely wilderness, while settlers slowly made their way there and increasingly pushed native tribes west. In 1803, the area came under U.S. control as part of the Louisiana Purchase.

The following year, at the request of Thomas Jefferson, William Dunbar led the first official American expedition to survey and study the hot springs, arriving from the south by way of the Ouachita River. By this point, word of the palliative properties of the warm waters had spread, as Dunbar’s group found that rudimentary shelters had already been erected by transitory visitors. Permanent settlement began in 1807, and though modest at first, the springs’ popularity gradually rose among those seeking relief from joint pain, liver problems and a host of other maladies, as well as opportunists and entrepreneurs looking to tap the springs for profit.

A wood-engraved illustration from the January 1878 issue of Harper's New Monthly Magazine shows the Big Iron Bathhouse in Hot Springs. Credit: Harper's New Monthly Magazine, public domain.

With most visitors opting for temporary stays over the summer, the year-round population had grown to only about 150 according to the 1820 census, but the burgeoning township had just seen its first hotel built, and transplanted locals were beginning to offer lectures and medical advice about the springs. Bathing facilities remained fairly primitive, primarily consisting of spring water funneled to makeshift tubs carved in the ground, some with crude shacks or tents built over them. In the first step toward what would become the indelible hallmark of Hot Springs, the earliest bathhouses — consisting of simple log cabins featuring wooden tubs and sweat rooms — were constructed in the early 1830s.

As early as 1820, recognizing the springs’ value, the newly formed Arkansas Territorial Legislature had begun petitioning the U.S. government to grant federal protection to the area around the hot springs. More than a decade later, Congress passed a bill stating that the springs, together with areas of land around them “shall be reserved for the future disposal of the United States, and shall not be liable to be entered, located, or appropriated for any other purpose whatever.” President Jackson signed the bill — which did permit the territorial government to lease the land provided “the rents and profits arising from said springs” were applied to the construction and maintenance of roads in the young territory — into law on April 20, 1832, thus marking the creation of the first such federally reserved land.

At the root of the Hot Springs’ popularity is its geology, which funnels rainwater deep underground before returning it to the surface. The sedimentary rocks in the area — layers of shale, sandstone, chert and novaculite, a microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz best known from deposits in the Ouachita Mountains — were deposited from the Ordovician through the Early Carboniferous. Over time, the layers underwent several episodes of compressional deformation, which created the area’s low mountains as well as a series of synclines, anticlines and northeast-southwest-striking thrust faults.

Exposures of the Bigfork Chert, along with the overlying Arkansas Novaculite and Hot Springs Sandstone, are thought to be the main recharge areas for the springs, through which rainwater seeps over thousands of years to estimated depths of 1,370 to 2,300 meters. At depth, it is heated geothermally and takes on new chemistry as it leaches ions from the rocks, before rising relatively quickly along a pair of deep faults. Closer to the surface, the water mixes with a portion of young, cold groundwater and is channeled by shallow faults and joints to dozens of individual springs at the base of Hot Springs Mountain.

The exact number of springs in the area has changed over time, as some have been destroyed and others stopped flowing. A 2006 study by the U.S. Geological Survey noted that 43 springs were known to be flowing at the time, issuing a total of more than 2 million liters of heated water each day. The temperature of the waters, which emerge virtually sterile and contain high concentrations of bicarbonate, calcium and silica relative to rainwater, averages a scalding 62 degrees Celsius. (For use in bathing, the water is cooled to about 37 degrees.) Runoff from the hot springs is carried away by nearby Hot Springs Creek, which flows south toward the Ouachita River. Prior to widespread development of the area, the creek banks were lined with natural tufa deposits that formed as calcium carbonate precipitated from the freshly liberated spring water.

Today, most of the springs are capped and managed by the National Park Service. Here, free-flowing spring water cascades through man-made display fountains in the park. Credit: ©Brandonrush, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported.

With improved transportation from Little Rock in the mid-1830s, more and more people made the trek to Hot Springs. Along with the growth in tourism, the pace of development picked up as well, stoked by private entrepreneurs who staked claims to land despite its supposedly protected status. Four decades after the area’s designation as a federal reservation, its year-round population had grown to 3,500, with 50,000 people visiting annually.

It wasn’t until the late 1870s that the U.S. government restated its claim to the springs and surrounding hills and began regulating the distribution, sale and consumption of the area’s natural waters. Beginning in the late 19th century, Hot Springs was gradually converted into the luxury vacation spot that it would be known as through the mid-20th century. Most of the springs were capped and a central treatment and distribution system was built to divert, combine and cool the water before it was then doled out for consumption in baths and drinking fountains. Several episodes of construction resulted in numerous private bathhouses opening — at the most, about two dozen operated simultaneously — most of which catered to well-heeled clients. (Government-run bathhouses were also built to treat the indigent.)

The Ozark Bathhouse, photographed here in 2008, is one of eight historic bathhouses along Bathhouse Row. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

Hot Springs’ notoriety surged in the early 20th century. And about the time of its instatement as a full-fledged national park in 1921, the aptly named Bathhouse Row had taken on much of its iconic flamboyance. This was the era when famed bathhouses like the Hale, Fordyce, Superior and Maurice, among others, added fountains, promenades, stained glass and other luxury appointments, and when they adopted the ornate exterior facades still seen today.

Beginning about 1950, however, the popularity of the bathhouses declined markedly. By 1987, only seven facilities were still using spring water supplied by the National Park Service. And today, just two of the historic bathhouses on Bathhouse Row — the Buckstaff and the Quapaw — are operating as such (the latter reopened in 2008). Meanwhile, the Fordyce has been repurposed for tours as the park’s visitor center, and the Lamar houses the park gift store. The Hot Springs Museum of Contemporary Art had until recently been housed in the Ozark Bathhouse, but it was closed in fall 2013 due to financial issues.

In addition to Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park, which now covers about 22 square kilometers, offers camping and 41 kilometers of hiking trails in the mountains surrounding the northern part of the city of Hot Springs. In recent years, about 1.3 million recreational visitors have visited this most diminutive national park annually, making it the 15th most-visited in the country. While relatively few guests now partake in the spring-fed baths, the mineral-rich waters of the area still flow. And though it may have followed Yellowstone, Yosemite and about 17 others onto the roster as official national parks, proponents of Hot Springs still maintain that it was the first all along.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.