by Rossie Izlar Wednesday, September 28, 2016

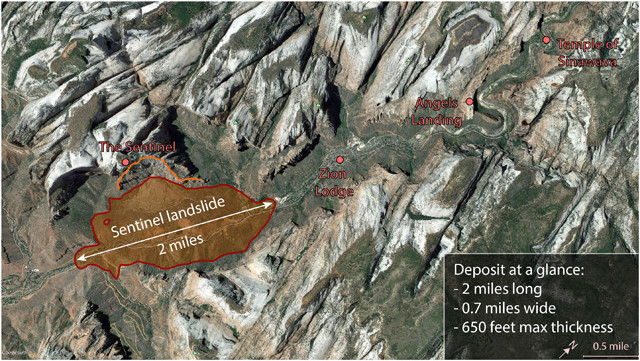

Zion Canyon in Utah's Zion National Park has a flat valley floor that was created when part of Sentinel Peak collapsed in a giant landslide, creating a dam and forming a lake that eventually filled in with sediment. Credit: courtesy of Sarah Meiser.

It took about 20 seconds for the Sentinel rock landslide to tumble into Zion Canyon, but those seconds changed the landscape for thousands of years.

Zion Canyon is a wide, flat-bottomed valley set among the towering walls that characterize Zion National Park. It owes its flatness and its accessibility to a violent landslide that occurred approximately 4,800 years ago, with a volume of 286 million cubic meters — enough debris to fill 114,400 Olympic swimming pools — according to new research in GSA Today that pinpointed the timing and magnitude of the event.

Volunteer Scott Castleton and University of Utah geologist Jeff Moore collect samples from boulders to date the Sentinel slide. Credit: Jessica Castleton.

Researchers have known for decades roughly how the canyon formed; the last major publication on it was in 1945. A large section of Sentinel Mountain — including its peak and the wall below it — came crashing down and dammed the west branch of the Virgin River, which runs through the rocky landscape. The dam created a lake that lasted for 700 years. Eventually the river cut through the dam, filling it with sediment and transforming the lake into a flat plain.

Geologist Jeff Moore from the University of Utah investigated the dynamics of landslide that created Zion Canyon: “We wanted to give it a modern treatment and throw all our modern tools at it,” Moore says.

Using a method called cosmogenic dating, his team sampled 12 boulders to see how long they had been exposed to the sky. “The boulders that were previously part of the cliff part had been staring up at the sky for the last 4,800 years,” Moore says. “So we were able to directly date the landslide using the boulders.”

This Google Earth image of Zion Canyon shows the location of the landslide 4,800 years ago, that collapsed off Sentinel Peak (orange line shows the collapse location) and dammed the Virgin River to create a lake. Over 700 years, the lake eventually filled with sediment, producing the flat, canyon floor enjoyed today by millions of visitors to Zion National Park.. Credit: Jeff Moore, University of Utah.

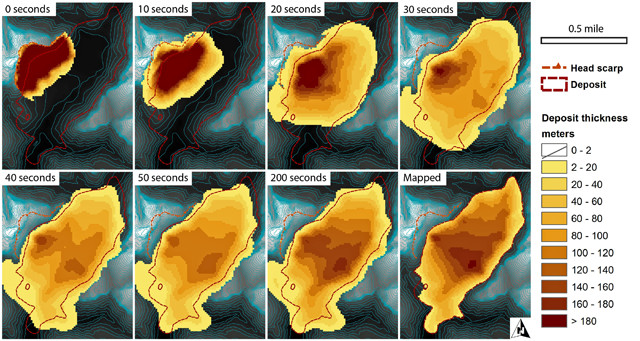

Moore and his colleagues also determined the magnitude and speed of the landslide as it tumbled into the canyon below using known landslide deposits to create an animated simulation. The flow of rock and sediment reached speeds of up to 90 meters per second, they reported. A minute after the slide began, the debris settled over a 3.3 kilometer area.

“Their model shows that the speed and the duration of the event was pretty impressive,” says Dave Sharrow, a hydrologist who works for the National Park Service in Zion but was not involved in the new study. “The whole thing came down, hit the far wall, sloshed back, and came to rest in about in a minute.”

A simulated sequence of the Sentinel landslide: The first six frames show the progress of the rock-avalanche landslide, which lasted about a minute. Darker brown indicates thicker slide deposits; yellow indicates thinner deposits. The last two frames compare the slide after it was at a complete standstill, which took about 200 seconds. The reconstruction is based on geological mapping of the actual landslide deposits. Credit: Jeff Moore, University of Utah.

Moore’s team helped clear up some “bogus” information on the landslide, Sharrow says, including how long it took for the prehistoric lake to fill with sediment. “Zion Canyon is one of the best examples we have of a filled canyon bottom that has this flat, park-like base,” he says. “We have other prehistoric dammed canyons that created features like this, but they are quite a bit smaller.”

The Virgin River will continue to cut through the canyon, and eventually it will revert the area back to its narrow and inaccessible state, Moore says. But for now, “the avalanche gave us this wonderful 10,000-year period where the canyon is fantastically available and unique.”

This view looking up Zion Canyon shows the remains of the Sentinel landslide, denoted by the red line. Credit: Jeff Moore, University of Utah.

Moore says he’s always on the lookout for “charismatic avalanches” — landslides that have a constructive and beautifying effect. “My day job is all about the gloom and doom and the potential hazards of landslides,” he says. “But I really enjoy studying the ones that had a role in creating something beautiful.”

Millions of people visit Zion National Park every year. This study will help the National Park Service tell the story of the ancient landslide that made it possible for visitors to enjoy a picnic under the cottonwood trees in Zion Canyon, Sharrow says.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.