by Mary Caperton Morton Monday, May 4, 2015

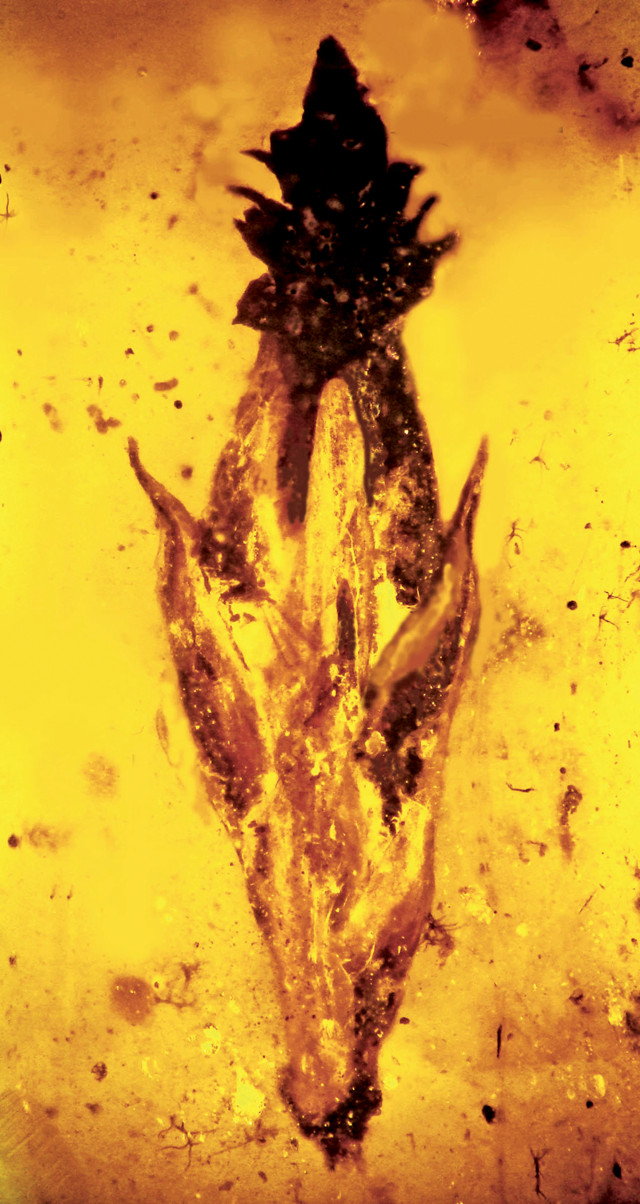

This 100-million-year-old amber-encased specimen contains what could be the oldest grass fossil known, and the only fossilized specimen of the fungus ergot (dark material at top) ever found. Credit: Oregon State University.

Delicate grasses don’t preserve well in the fossil record, and evidence for grasses coexisting with dinosaurs is scant. But according to a new study, a chunk of 100-million-year-old amber recently discovered in Myanmar appears to contain the world’s oldest grass fossil — far more ancient than any fossil grasses previously found. What’s more, the specimen seems to be topped with the world’s oldest known ergot — a fungus containing ingredients used to make lysergic acid diethylamide, better known as LSD. But while the image of a 100-metric-ton sauropod grazing on hallucinogen-laced grass is intriguing, not everybody is convinced that the specimen is the real deal.

Until recently, the earliest, reliably identified grass fossils dated to about 55 million years ago, after the dinosaur mass extinction. However, studies of dinosaur coprolites — that is, fossilized feces — hint that at least some dinosaurs may have grazed on grass in the Late Cretaceous before they disappeared. If confirmed, the single strand of grass found in the amber block from Myanmar would push the evolutionary timeline of grasses back by almost 50 million years.

“Amber gives us a look at past environments that we don’t get in other types of fossils,” says George Poinar, a botanist at Oregon State University in Corvallis and lead author of the new study, published in the journal Palaeodiversity. Amber fossils are formed when tree sap flows around a plant, insect or animal, encasing and preserving it as the sap hardens over time into a semiprecious stone.

Poinar says he first thought the Myanmar specimen was a flower, but upon closer inspection, he identified it as a spikelet — the flowering stage of grass. Sitting atop the spikelet was a dark cluster of fungus that Poinar’s colleague, plant pathologist and mycologist Stephen Alderman of the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Corvallis, identified as fossilized ergot.

Ergot is infamous. In the Middle Ages, ergot poisoning plagued Europeans when rye grains infected with the fungus commonly produced outbreaks of “Saint Anthony’s Fire,” a severe burning sensation in the limbs, which could sometimes lead to gangrene of the extremities as well as hallucinations and convulsions. In modern times, ergot is a source material for the production of lysergic acid, a chemical precursor for LSD.

“This is an important discovery that helps us understand the timeline of grass development,” Poinar says. “It also shows that this parasitic fungus may have been around almost as long as the grasses themselves, as both a toxin and natural hallucinogen.”

Credit: Callan Bentley.

Poinar acknowledges, however, that there is no way to know whether, 100 million years ago, the ergot had already evolved its hallucinogenic properties, thought to function as a defense mechanism against grazing animals.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that grasses infected with ergot would have been eaten by sauropod dinosaurs, although we can’t know what exact effect it had on them,” he says. Livestock such as cows, pigs and sheep can get ergot poisoning from eating Claviceps purpurea, a species of ergot that infects rye and other cereal plants. The preserved specimen of ergot, now extinct, was named Palaeoclaviceps parasiticus.

Further study will be needed to confirm that the specimens are indeed grass and ergot, says William Crepet, a plant biologist at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., who was not involved in the new study. “Specimens in amber can be difficult to work with, and this study doesn’t pass my standards for rigor,” he says.

Because the one-of-a-kind fossil is so delicate, Poinar’s team declined to run additional tests on the specimen, mainly categorizing it using noninvasive high-resolution microscopy. Crepet says Poinar and his colleagues could take CT scans of the specimen to study the internal structure of the plant materials inside the amber.

“Many people are looking for additional specimens at the mines in Myanmar,” Poinar says. “If additional specimens are found, we might be able to take cross sections or extract material for further testing.” For now, the specimen they have will be housed at the Museum of Natural History in Berlin.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.