by Sara E. Pratt Tuesday, December 9, 2014

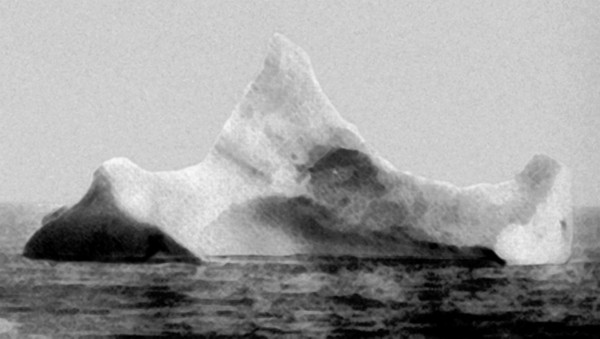

The iceberg responsible for the Titanic collision was never positively identified, but one purported to have a red streak of paint along its side was photographed on the morning of April 15, 1912, just a few kilometers south of where the Titanic sank. Credit: U.S. Coast Guard Navigation Center/www.navcen.uscg.gov.

A new study disputes the notion that an exceptional number of icebergs were floating in the North Atlantic the year the Titanic collided with one at roughly 42 degrees North latitude and quickly sank, killing more than 1,500 people. However, the study also suggests that weather conditions around the time of the sinking likely pushed icebergs farther south than normal for that time of year.

The new analysis of records of the movement of sea ice in the North Atlantic reveals that 1912 wasn’t that unusual, with 1,038 icebergs crossing south of the 48 degrees North latitude line. “The Titanic set sail in a year when sea-ice transport and iceberg calving rates were high, but not exceptionally so,” Grant Bigg and David Wilton, earth systems scientists in the department of geography at the University of Sheffield in England, wrote in Weather, the journal of the Royal Meteorological Society.

The researchers suggested that a ridge linking two high-pressure systems over the North Atlantic around the time of the sinking drove frigid winds out of northeastern Canada and over the western North Atlantic. “These winds and temperatures, assisted by the prevailing southward flow of the ocean’s Labrador Current on the Grand Banks, led to icebergs and sea ice being transported farther south than normal for the time of year — but not beyond the known limits for icebergs during the 20th century,” they wrote in a related article in the statistics journal Significance.

The team also modeled the path and origin of the iceberg, which was thought to have come from Jacobshavn Glacier in western Greenland, finding instead that it most likely originated in southwest Greenland, and had calved in fall 1911. The berg — which at the time of the collision was about 125 meters long and 100 meters thick, with 15 to 17 meters exposed above the water line, and a mass of 2 million metric tons — had melted on its way south. The researchers estimate the iceberg was originally 500 meters long by 300 meters deep and weighed 75 million metric tons.

The maritime disaster led to the formation of the International Ice Patrol to monitor icebergs in the North Atlantic and track the annual southward ice limit. It has been managed by the U.S. Coast Guard since 1913.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.