by Kate S. Zalzal Tuesday, August 15, 2017

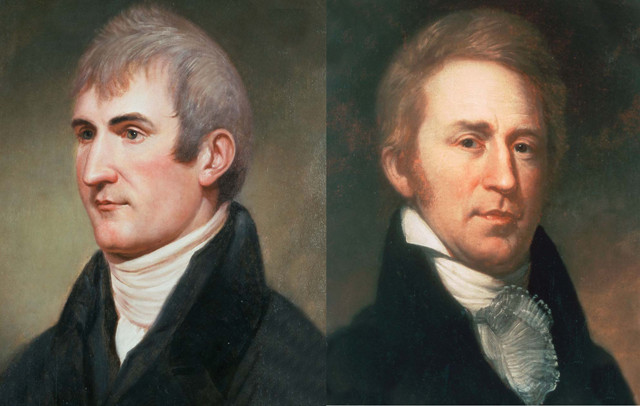

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who, from 1804 to 1806, led the expedition of the Corps of Discovery to explore the United States' newly acquired territory. Credit: both: public domain.

It’s been called the greatest camping trip of all time. Statues, counties, waterways, mountains, military vessels, and even two colleges bear the names of the journey’s leaders. Their journals are among our greatest national treasures, and their adventures have inspired generations of explorers. Two hundred and eleven years ago this month, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their 31-man Corps of Discovery returned to St. Louis, the frontier town where they had started their journey 28 months and nearly 13,000 kilometers of wilderness earlier on May 14, 1804.

When they arrived by boat via the Missouri River into St. Louis, they carried with them countless treasures. In addition to the knowledge of new rivers, mountains, canyons and ecosystems, they brought back maps, sketches, seeds, pressed plants, animal skins, and detailed descriptions of native tribes, their languages, customs and leaders.

They also brought back tales of their encounters with grizzly bears, rattlesnakes, massive herds of bison and elk, roaring waterfalls, and the towering trees of the Pacific coast. These days, their journey is widely known as a spectacular feat of daring and great scientific discovery that helped fill in the outlines of a nearly blank map of the Northwest.

But this has not always been so. Following the tragic and untimely death of Meriwether Lewis in 1809, their journals — and the great geographic, cultural and scientific discoveries within — were largely forgotten for nearly a century. Once rediscovered, the expedition enjoyed a revival of interest. Today, in an age when few unexplored places remain on Earth, the Lewis and Clark expedition continues to fascinate and inspire.

The idea of a western expedition to the Pacific Ocean was on Thomas Jefferson’s mind long before he became the third U.S. president in 1801. Jefferson longed to know what lay beyond the borders of America, particularly following the acquisition of the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803, which doubled the size of the country. He believed that America’s future lay in its westward expansion, the establishment of international trade routes and the incorporation of Native tribes under the umbrella of American sovereignty.

Jefferson named Lewis, a captain in the U.S. Army and Jefferson’s personal secretary, to lead an expedition that could unlock the vast unknown expanse beyond the Mississippi River. Aware of the potential political challenges of such an expedition, Jefferson crafted objectives for the men that would appeal to the various powerful parties in the nation’s capital, and loosen the purse strings to fund the $2,500 journey (between $40,000 and $50,000 in 2016 dollars). Their main goal was to find an all-water route to the Pacific, the fabled Northwest Passage. Along the way, Lewis was to peacefully connect with native tribes and begin to bring them into American orbit, learning about their religions to help “those who may endeavor to civilize and instruct them.”

The route of the expedition of the Corps of Discovery, led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, from May 1804 to September 1806. Credit: National Park Service/K. Cantner, AGI.

Lewis was to learn what he could of the British fur trade, with the goal being to eventually push them out in favor of U.S. interests. He was to determine if the country around the Missouri River was large and fertile enough to support a sizeable population of American pioneers. He was also to document the soils, minerals, flora, fauna and the presence of fossils and volcanoes. He was to make maps and collect and preserve specimens. And he was to do all of this while navigating uncharted wilderness and keeping order within the corps.

To prepare, Lewis embarked on months of study with Jefferson and leading U.S. scientists, learning botany, mapmaking and zoology. After bringing Capt. William Clark, under whom he had served in the Army, into the corps as a co-leader, Lewis was ready.

When the Corps of Discovery embarked in 1804, there was much speculation about what lay beyond the Mississippi River. Based on a previous report by a Scottish fur trader that described a relatively easy passage across the Continental Divide in Canada, Lewis and Jefferson expected the Rocky Mountains to be more like the Appalachians. Lewis also carried an idea, imparted by his anatomy tutor, that there might still be mastodons out on the prairie.

In spring 1804, the expedition began traveling upstream in a massive keel boat heavily loaded with supplies, against the current of the Missouri River through what is now Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, South Dakota and North Dakota. They experienced the mission’s first and only fatality on Aug. 20, 1804, near what is now Sioux City, Iowa, when Sergeant Charles Floyd died of “bilious colic,” which was most likely appendicitis. The corps buried him atop a bluff overlooking the river, which they named after him.

Along the way, they encountered the Yankton Sioux, who were friendly, and the Teton Sioux, with whom the corps had a tense moment when three warriors demanded more trade goods and seized one of their canoes, threatening to not let them leave, before backing down and allowing the corps to move on.

The corps reached central North Dakota, near what is today Bismarck, in late October, as the river was already icing over. They decided to overwinter near the villages of the Mandan tribe — which together were home to 4,500 people, larger than the populations of either St. Louis or Washington, D.C., at the time. The corps built Fort Mandan, where they spent a cold, harsh winter, with temperatures reaching minus 40 degrees Celsius.

In November, the corps hired a French Canadian fur trapper, Toussaint Charbonneau, and his young Shoshone wife, Sacagawea, as interpreters. She had been kidnapped by the Hidatsa and sold to Charbonneau, and she now carried his child. From Fort Mandan, several members of the corps took the keel boat back to St. Louis to deliver a detailed map of their journey so far. They also sent back notes about their interactions with the native populations they’d met and details of the new animals they’d seen. Five live animals were included in this return shipment, including a black-tailed prairie dog that lived out the rest of its days at the White House.

In spring 1805, the corps left Fort Mandan, continuing to follow the Missouri River. With them was Sacagawea, carrying on her back her infant son, Jean Baptiste, whom she had delivered in February, as well as Charbonneau. Through the summer, the group paddled upstream, searching for the headwaters of the Missouri, and the Shoshones, from whom they needed to obtain horses to cross the mountains.

In June 1805, they reached the impassable Great Falls of the Missouri, necessitating a grueling, month-long portage of the canoes and supplies to bypass the falls and put back in upstream. In July, they reached a point where the Missouri branched into three forks, which Sacagawea recognized as the area where she had been kidnapped as a child — in Shoshone territory.

"Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia" a painting by Charles Russell, depicts an encounter between a native coastal tribe and the Corps of Discovery. Sacagawea is painted standing up in the boat, raising her hands in peace. Her presence on the expedition helped assure tribes that the Corps of Discovery was not a military force. Credit: Charles Russell/Library of Congress.

On Aug. 13, 1805, Lewis finally made contact with the Shoshone, whose chief, in a famous historical coincidence, was Sacagawea’s brother. The corps traded for horses and, in September, left the site that Lewis had named Camp Fortunate, now led by an elderly Shoshone guide who joined the motley crew. As they continued north, the guide informed them that the Great Falls lay four days' walk to the east through a pass. By deciding to follow the Missouri to its headwaters, the corps had followed a more circuitous route that took 53 days.

They passed over the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass, Idaho, and trudged through the steep and snowy Bitterroot Mountains — which Sergeant Patrick Gass described in his journal as “the most terrible mountains I ever beheld” — while subsisting on starvation rations. Eleven days later, after 265 kilometers on the Lolo Trail, they stumbled out of the mountains near the border of Idaho, where they met the Nez Perce. The tribe befriended the strangers, and the weakened corps members stayed with the Nez Perce for several weeks regaining their strength and building dugout canoes before continuing their journey.

On Oct. 7, 1805, the group put in their canoes on the Clearwater River and began traveling swiftly — downstream now, for the first time since leaving St. Louis more than a year and a half before — to the Snake River and, finally, into the Columbia River, which led to the Pacific Ocean.

The corps first heard the roar of the Pacific Ocean on Nov. 7, 1805. Clark wrote in his journal, “Ocian in view! O! the joy,” though, as it turned out, they’d reached only the Columbia River Estuary, where foul weather trapped them for a few weeks before they actually reached the coast.

They built Fort Clatsop and spent their second winter of the trip along the southern bank of the Columbia River near present-day Astoria, Ore. Although the corps had hoped to encounter a ship to replenish supplies and send back news of their success, they did not. During the long, wet winter, Lewis rewrote his journals while Clark worked on the map. Clark estimated they had traveled 6,698 kilometers since leaving St. Louis. Later calculations showed he was off by only 64 kilometers.

On March 23, 1806, they began rowing up the Columbia on the long journey home. By May, they were back with the Nez Perce in Idaho, where they split into two groups. Lewis took the shorter pass to Great Falls and headed along a northern route to explore the Marias River and Blackfeet territory, while Clark went back over the grueling Lolo Trail and down the Yellowstone River, this time with a Nez Perce guide.

While exploring the Marias River in Montana, part of Lewis' group had a deadly encounter with a band of Blackfeet warriors. Near what Lewis called Camp Disappointment, two Blackfeet warriors were killed as they tried to run off the corps' horses and steal their guns. Fearing reprisals from the larger tribe, Lewis and his men rode for 24 hours, arriving at Great Falls just as the rest of his group rounded the bend in the canoes. Two and a half weeks later, on Aug. 12, 1806, they met up with Clark’s group at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri and traveled on to Fort Mandan. There they bid farewell to Sacagawea, Charbonneau and Jean Baptiste, now 18 months old, whom Clark promised to send to school in St. Louis.

After two years with no communication, the men of the Corps of Discovery were anxious to return home. On the last leg, they rowed hard downstream, covering 100 to 130 kilometers a day. They ate mostly fruit gathered quickly from the shore as they didn’t want to take time to hunt for game, which became scarcer as they neared St. Louis. Most had already given up the corps as lost, so when word reached the town that the buckskin-wearing men were returning, most of the town’s roughly 1,000 residents turned out on the river bank to celebrate the heroic accomplishment.

On the return trip, Capt. Clark discovered this sandstone butte along the Yellowstone River and named it "Pompeys Tower," after his nickname for Sacagawea's infant son. On July 25, 1806, he etched his name and the date into the rock, creating the only known mark on the landscape left by the expedition. Credit: BLM.

Foremost on Lewis' mind was President Jefferson. He quickly wrote to him to share their news: They had survived, reached the western edge of the continent via land and made numerous discoveries. But, they had not found a continuous waterway to the Pacific, or even an easy portage between the Missouri and Columbia rivers, as had been hoped.

What they did find exceeded their expectations: The mountains were bigger, the terrain tougher and the bison more numerous. The journals contained the first detailed maps — 140 in all — of the region’s extensive waterways and landscapes, plus systematic reports and scientific measurements of the environment, including descriptions of at least 120 species of animals and 180 species of plants that were previously unknown.

Upon the corps' return in 1806, excitement and curiosity abounded over what the group had discovered. Although Lewis intended to have the journals and maps published quickly, they were not; and there has been much speculation as to why he was delayed in this important task. He was appointed governor of Upper Louisiana in 1807 and became immersed in his new role in St. Louis. Meanwhile, other parts of Lewis' life began to unravel. He was unsuccessful in his attempts to marry, and he reportedly had bouts of frequent drinking, financial troubles and depression, which he had also battled prior to and during the journey. In 1809, Lewis left St. Louis, planning first to go to Washington to resolve some complaints about his performance as governor, and then to Philadelphia to begin the publication process.

Before leaving, he met with Clark, who had also settled in St. Louis as the U.S. Agent of Indian Affairs. Clark had established a reputation for trying to help the native populations he had met on the expedition, who were not faring well under European expansion. The two men remained close after the expedition, Clark even naming his son Meriwether Lewis Clark. Clark agreed to meet up with Lewis once he was in Washington, D.C., to help him sort out his troubles. Clark later wrote to his brother of this meeting with Lewis: “I do not believe there was ever an honester man in Louisiana nor one who had pureor motive than Govr. Lewis … I think all will be right and he will return with flying Colours to this Country.”

But on the journey east, Lewis fell further into despair. Early on the morning of Oct. 11, 1809, while lodging at an inn along the Natchez Trace outside what is now Nashville, Tenn., Lewis shot himself. His journals were safely nearby, wrapped up in his saddle bags.

In the aftermath of Lewis' death, Clark and Jefferson had trouble finding a suitable editor and publisher for the journals. They were placed for safekeeping with the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, where they remain today. In 1814, a book paraphrasing the journals was published, but it excluded much of the animal and plant discoveries and it sold slowly. Over the next 90 years, much about Lewis and Clark’s expedition was forgotten. Plants, animals and geography that they had first discovered and named were discovered and named again by later naturalists.

It wasn’t until 1904, nearly a century after their return to St. Louis, that a complete edition of the journals was published. Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites, the publication sparked a revival of interest in the Lewis and Clark expedition that remains to this day.

Lewis and Clark’s exploration was America’s “epic voyage, their account of it is our epic poem,” wrote historian and author Stephen E. Ambrose in 1997. The efforts of Lewis, Clark, Sacagawea and the Corps of Discovery expanded the map and opened America’s chapter of westward expansion — and all that followed.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.