by Kate S. Zalzal Friday, July 21, 2017

Charleston suffered widespread damage from the 1886 earthquake. Credit: USGS.

In late August 1886, Charleston, S.C., was in the grip of a heat wave. It was so hot during the day that many offices were closed and events were postponed until later in the evening when temperatures had cooled. So, when powerful seismic waves rippled across the city at 9:51 p.m. on Tuesday, Aug. 31, 1886, people were sent scrambling not just out of homes, theaters and the opera house, but out of churches, offices and other buildings in which they might not have otherwise been at that late hour.

Many of those who were at home were preparing for bed, finally free of the heavy clothing of the Victorian South. As the earthquake struck homes in both the grand, classically designed residences of the upper-class white neighborhoods and the wooden shacks that housed much of the city’s growing black population, people dashed into the streets. Regardless of their social standing, residents found themselves out on the steamy streets in varying degrees of dress, many barefoot. The air was filled with dust, sent up from the dry ground as roofs, chimneys and columns crashed to Earth. White dust from brick mortar and plaster, which had been sheared and pulverized as the rolling ground pulled down walls, now coated a mass of terrified Charlestonians.

Shaking from the earthquake was felt from Maine to Florida and as far west as the Mississippi River, covering an area of more than 5 million square kilometers. The earthquake — estimated to have been at least a magnitude-7 event with an epicenter near Summerville, S.C. — was the most powerful and destructive in recorded history to strike in the southeastern United States. It is an unusual location for such an event. South Carolina sits in the middle of the North American Plate, far from active tectonic boundaries. Research indicates that the rupture of this rare, intraplate earthquake occurred on an ancient, buried fault thought to be a remnant of the breakup of Pangea during the Mesozoic.

Approximately 100 people died during the earthquake, which nearly leveled Charleston, and many more were injured. The earthquake also exacerbated growing racial tensions in the Post-Reclamation South. Scientifically, however, the calamity spurred significant advances in seismology.

William J. McGee of the U.S. Geological Survey inspects damage on Tradd Street in Charleston. Credit: USGS.

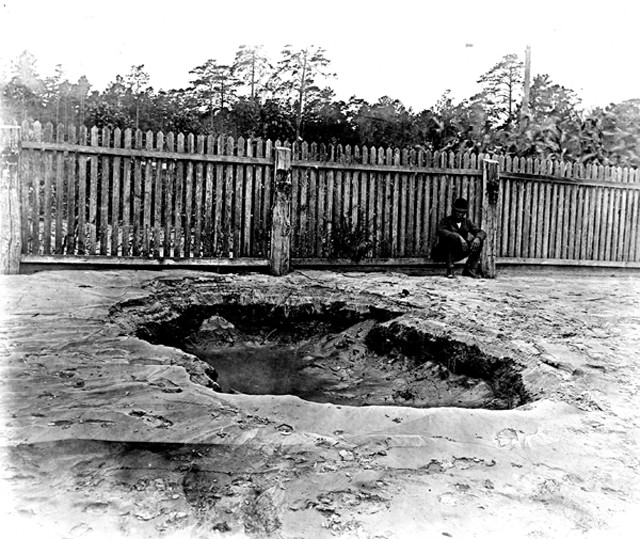

The rumbling of the mainshock that night lasted nearly a minute — damaging and collapsing thousands of buildings across South Carolina. Railroad tracks in Charleston and the surrounding area buckled and trains derailed. At least one railroad trestle lurched 2 meters. Dams broke, flooding farms and roads. Forty kilometers outside of Charleston, a fissure more than 600 meters long opened up. Countless other smaller fissures ripped apart the sandy coastal plain as water shot up or bubbled out of the cracked land. The ground liquefied in many spots, causing additional damage to buildings, roads, bridges and farm fields. Sand blows — small volcano-shaped structures resulting from seismically induced liquefaction — popped up across the landscape, further evidence of the powerful forces at work belowground.

When the shaking began, some thought it was from a passing streetcar or a nearby train. But as the rumble turned to a roar and the buildings around them began to crumble, many Charleston residents settled on a biblical explanation: Judgment day had arrived. People prayed and preached in the streets and parks across the city, their fears and fervor growing as tremors continued wracking the city for weeks after the quake. Preachers called on residents to repent, telling them the end was near and that God was angry with them. Given the city’s tumultuous past, Charlestonians had reason to fear.

A small crater near Charleston formed by liquefaction during the quake. Credit: USGS.

The port city of Charleston was founded in 1670 by the British on a narrow peninsula along the sandy, coastal plain of South Carolina. Nestled among several rivers, the area was originally marshland, but much of it was filled in for farming and building during the first 200 years of the city’s history, which was not without consequences. Flooding from high tides and heavy rains, and land subsidence, which causes buildings to tilt and develop structural problems, have plagued the city since its founding.

Charleston was a hub for slave ships arriving from Africa during Colonial times. When hostilities between the North and South began boiling over in late 1860, South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union, and its Confederate forces fired the first shots of the Civil War in April 1861, claiming Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. In the years after the Civil War, free blacks flocked to Charleston, part of a growing class of educated and skilled tradespeople. With the tension of shifting social structures, violence and rioting were common.

When the earthquake struck in 1886, Charleston was still recovering from a violent hurricane that had hit the year before. Much of the damage from the storm still had not been repaired. And before that, the Great Fire of 1861 had ripped through the city, leaving behind a burned area still present at the time of the quake.

The quake derailed a locomotive on Ten Mile Hill northwest of Charleston. Credit: USGS.

In the days after the quake, reporters from across the country clambered to get into Charleston. Once there, they often sent back sensational and dramatic tales of the disaster, looking to gain a competitive edge in readership. At the time, competition among newspapers was particularly fierce throughout the South as cities damaged during the Civil War fought to regain their footing as leaders in the New South. In contrast, Frank Warrington Dawson, editor of the News and Courier in Charleston, emerged as a hero and leader for his steadying voice in the days and months after the quake.

After the mainshock ended, Dawson rounded up what staff he could find and a new headline was quickly inserted into the following day’s paper: “A Terrible Earthquake. The Whole City Injured. The Most Disastrous Event in the City’s History … The loss is not as great as it seems to be.” Even amid the continued aftershocks of that night, Dawson fought to project Charleston as a city in control of its fate and headed for greatness.

The most immediate challenge was to house people who had either lost homes or were too scared to sleep indoors for fear the rumbling would begin again. Sails from ships in the harbor were used as tents. Any structure with a floor and roof was converted into housing, including railroad boxcars, stables, the cargo hold of a steamship, and boats docked in the harbor. At first, blacks and whites camped together, but tensions quickly led to the establishment of largely segregated camps. Poor sanitation and a lack of sewers, already a problem before the earthquake, now became a crisis that further fueled racial and class conflicts.

“Shattered were the walls that separated rich from poor, white from black, neighbor from neighbor,” wrote Susan Millar Williams and Stephen G. Hoffius in their 2011 book “Upheaval in Charleston: Earthquake and Murder on the Eve of Jim Crow.” The earthquake had shifted not only the ground, but also the tenuous social structure of the city, Williams and Hoffius wrote.

In the two decades since the end of the Civil War, Charleston had made notable progress in racial equality. It was less segregated than some other Southern cities, and its black residents had growing political influence. When the earthquake struck, there was no formal system for supplying federal or state financial aid. A complex, subjective system of doling out support developed, with Frank Dawson often playing a role in the distribution of aid. Poor people and blacks became angry at a system they saw as promoting the status quo rather than helping those most in need. Upper-class whites were angered as they thought the relief efforts seemed more helpful to tradesmen, who used the opportunity to demand better pay and safer working conditions.

A moderate voice who wanted a diverse and thriving Charleston, Dawson pushed back against a growing white supremacy movement that gained traction amid the turmoil. Three years after the earthquake, Dawson was murdered and his killer acquitted. The physical and social upheaval of the earthquake uncovered and reignited old conflicts, moving the city toward the era of Jim Crow laws that soon followed and codified racial segregation for decades.

Displaced monuments in a cemetery in Charleston. The direction and type of damage to these monuments helped McGee determine the earthquake's location and magnitude. Credit: USGS.

As fears of the impending apocalypse receded, people became curious about the cause of the event. Was it God’s wrath, or merely a natural, measurable phenomenon? Little was known about the nature of earthquakes at the time. The first treatise on seismology was published in 1862 following Irish geophysicist Robert Mallet’s investigation into the Neapolitan earthquake of 1857, which first associated different types of rock and sediment with different seismic wave velocities — a fundamental tenet of seismology.

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) saw the Charleston earthquake as an opportunity to advance the nascent field of seismology. John Wesley Powell, USGS director at the time, sent William J. McGee to Charleston to investigate. McGee, a geologist and one of the founders of the Geological Society of America, was in Washington, D.C., at the time of the quake and felt the shaking on the third story of a brick building. According to his notes, McGee immediately realized what was happening and “attempted to determine the direction of [seismic] waves by observing sloshing of water in a washstand in the room.”

In Charleston, McGee worked with Thomas Mendenhall of the U.S. Signal Service, Ensign Edward Everett Hayden of the U.S. Navy and others, including local scientists and engineers, to measure and map the earthquake damage. Without seismological instrumentation, estimates of the earthquake’s location and size came from observations of physical damage, pendulum swing-directions in stopped clocks and watches, and personal reports detailing when and how the shaking occurred.

Eleven days after the quake, Hayden’s map showing contours of the arrival times of seismic waves at different locations was published in Science. The report showed that the epicentral area — the area of strongest shaking — was 25 kilometers to the northwest of Charleston in the small village of Summerville, which modern research corroborates.

Capt. Clarence E. Dutton, head of the Division of Volcanic Geology at USGS, compiled McGee and Hayden’s data into a comprehensive 325-page report, which was first abstracted in Science in 1887 and later published in USGS' 1887–1888 annual report, the agency’s ninth. The Dutton report was the largest and most thorough investigation of an earthquake in the United States at the time and remains the definitive account of the quake. Dutton estimated the mean velocity of “earth waves” (now called seismic waves) and introduced new methods for estimating focal depths (the depth of the earthquake rupture) from shaking intensity data. This work solidified the view that an earthquake entails the passage of waves of elastic compression through Earth’s crust. It also effectively buried the competing “shrinking Earth” theory that held that a cooling and contracting Earth led to earthquakes. Deployment of seismographs around the country jumped in the decade after the Charleston earthquake, as scientists and the general public began paying more attention to seismic activity and risk. nbsp;

Following the earthquake, buildings were shored up by inserting iron rods — a practice also used prior to the quake for structural reinforcement against hurricanes. The gib plates, washer plates and bolts visible on the exteriors of buildings were sometimes made to be decorative and, today, are often featured on historic tours of Charleston architecture. The Cleland House, on Tradd Street, was built circa 1730. Credit: Spencer Means, CC BY-SA 2.0.

The earthquake of 1886 was not the first to shake the region. Though large tremors occur infrequently, and many residents are unaware of South Carolina’s shaky past, historical accounts of earthquakes in the state go back as far as 1698. Research studying sand blows preserved in sediments along the coastal plain suggests the occurrence of seven large prehistoric earthquakes, four of which occurred in the last 2,000 years.

South Carolina continues to experience low levels of seismic activity today, averaging 10 to 30 quakes per year, two to five of which are large enough to be felt. In one 12-month period spanning 2011–2012, scientists recorded 134 small earthquakes in the Charleston-Summerville region. Some researchers suggest that this modern seismicity is still part of the lingering aftershock sequence of the 1886 event. South Carolina’s Emergency Management Division puts out guides to help residents understand regional and local seismic risks, and to be better prepared in the event of a substantial earthquake. As the landscape attests, Charleston — where the population has grown five-fold since the 1886 quake — will likely shake again.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.